An Appraisal by Mark Shiel

UCLA Film & Television Archive’s collection of TV newsfilm from KTLA is a historically significant collection, representing an invaluable resource for the study of Los Angeles and many other subjects through the lens of a pioneering local station. It is a product of what was, and still is, one of the most technically, economically, and organizationally advanced television markets, and it dates from an era—the 1960s and ‘70s—when the global, U.S., and Los Angeles economies went from boom to bust, although Los Angeles and its media industries grew rapidly throughout. The footage in the archive was produced and aired locally, and dealt with mainly local affairs, but it emanated from a city which was the sixth largest in the world by 1965, exceeded only by Tokyo, New York, Osaka, Mexico City, São Paulo, and Paris. Los Angeles had a much bigger global media profile than most of those other places, especially because of Hollywood, and it was also increasingly well known as a veritable laboratory of suburbanization, globalization, and racial violence, especially after the 1965 Watts uprising, which claimed 34 lives and cast a shadow over the city for decades.1

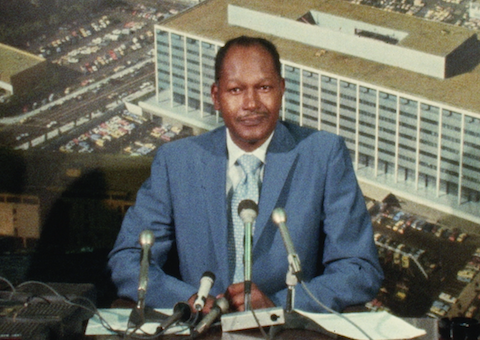

One of the most important media personalities running throughout the footage in the UCLA Film & Television Archive’s KTLA collection is Tom Bradley, Los Angeles City Council member from 1963 to 1973 and Mayor of Los Angeles from 1973 to 1993, a figure whose political career intersected with the city’s exceptional growth and social turbulence, not least because he was the first African American elected to each of those roles. KTLA news reports featuring Bradley allow us to see and gain an understanding of the mechanics and machinations of city government at a time when Los Angeles led many world urbanization trends, for better and for worse. The collection—now available for free streaming online—powerfully conveys a sense of Bradley’s conscientious management of the city’s many social, economic, environmental, and political challenges. These were especially numerous and complex when Bradley first became mayor, at a time of increasing fiscal austerity when many major cities (most famously, New York) teetered on the brink of bankruptcy, and when progressives in government and social movements struggled to make significant strides against massive constraints.

The Bradley clips in the KTLA collection focus on the period 1971-80 while dealing with seemingly all the major issues of the day, including race, civil rights, and the best way to run a major city on a limited budget while maintaining city services, transportation, policing, economic growth, and clean air and water. The range of issues and situations depicted is too large to enumerate one by one, but certain key themes recur. One is Bradley’s belief in the benevolent potential of good government, and his many comments in its favor despite what he acknowledges as numerous abuses of power by the federal government and corporations. In one clip he acknowledges public distrust because of the Watergate scandal, and in another he expounds on the Machiavellian scheme of General Motors and Standard Oil to undermine Los Angeles’ streetcar system in the 1940s and ‘50s. In several clips, Bradley calls for transparency in government—for example, when running for mayor for the first time, he mounts his own series of “alternative press conferences” to counteract what he deems the official propaganda of the incumbent mayor, Sam Yorty. Many clips demonstrate Bradley’s commitment to open-minded consultation with city government departments, labor and community groups, civic bodies, and business leaders, and Bradley often speaks directly about collaboration and dialogue as virtues in politics. These are values he emphasizes, for example, in chairing a November 1973 meeting with the mayors of nine municipalities along the route of the then-proposed 105 Freeway, and they are evident too in his friendly and professional interactions with other personalities such as Los Angeles City Attorney Burt Pines, L.A. City Council members Gilbert Lindsay, Edmund Edelman, and Marvin Braude, California State Senator James Mills, and California Governor Jerry Brown.

All the clips, by definition, show Bradley’s responsiveness to the news media, but they also reveal the ways in which he worked hard to appeal to, and communicate with, ordinary citizens. One clip from November 1973 shows a diverse crowd of men and women of all races, including children and the elderly, gathered in City Hall to petition the mayor about neighborhood issues ranging from crime to animal welfare, while another, filmed on Christmas that same year, shows Bradley doing a walkabout and shaking hands among shoppers and supporters outside Bullocks department store on Broadway in downtown L.A. Given the sobriety with which most city government business is transacted, in most of the clips the Bradley we see is understandably serious, careful, even methodical in his demeanor and words and yet seemingly thoughtful, patient, and sincere, rarely misspeaking and never flustered. In a few revealing clips we see a light-hearted Bradley, chuckling, smiling, or even sentimental—for example, when presenting an award to UCLA basketball coach John Wooden and praising him as “a special gentleman and a gentle man,” acknowledging that he finds the job of mayor “exciting, challenging, and very satisfying,” joking with reporters about the number of bicycles he saw on a diplomatic mission to China, or flanked by cheering teenagers when acting as umpire in a softball game.

On the other hand, Bradley speaks with gravity when addressing questions of law enforcement, public safety and the policies of the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD), questions which figure prominently in the archive given that the police department had the largest budget of any department in the city’s government, given Bradley’s own 22-year-long career as a police officer, and given that LAPD actions often proved controversial. In the KTLA clips, Bradley supports the police and expresses respect for their dedication and hard work, whether commenting on citizens’ anti-crime patrols, school security systems, police intelligence work, or police use of force. This is especially notable, for example, in a clip reporting on the May 1974 shootout in Compton between the LAPD and the leftist guerrilla organization known as the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA), six of whose members were killed. In that clip, Bradley insists police officers “were acting in the course of their duties, and without negligence,” but promises financial restitution to the community. In a later clip on the January 1979 shooting by LAPD officers of the young widow Eula Love, Bradley describes the event as “a terrible tragedy for this city,” arguing that support for the police must be balanced with respect for civil rights and calling on the Los Angeles Police Commission to review the case. Interestingly, in this and other clips, then LAPD Chief Daryl Gates listens in stony-faced silence, perhaps foreshadowing Bradley’s later clash with Gates over the beating of Rodney King by LAPD officers in 1991.

We see Bradley often arguing against racial inequality, although in moderate terms, as, for example, when he calls for public support for busing to desegregate Los Angeles public schools in September 1978, or the following year, when he argues for youth employment legislation by linking crime to “an unemployment rate which is at least 30%, sometimes 50%, among minority youth.” He frequently advocates a “total transportation program,” integrating roads, buses, rapid transit, and cycling, for both egalitarian and environmental reasons. Campaigning for mayor in 1973, Bradley argues that Sam Yorty does not understand the urgency of L.A.’s need for rapid transit because “he [Yorty] flies about this city from home to work or other places in a $150,000 helicopter paid for by the taxpayers.” In several subsequent clips, Bradley calls for public, financial, and legislative support for rapid transit. Outside City Hall in April 1974, he calls it “a great idea… to not rely solely on the automobile” as he greets a fleet of bicycles led by State Senator Mills in support of Proposition 5, which broke new ground by allowing state highway funds to be spent on public transportation. In other clips, Bradley argues for the importance of clean air, public parks in inner-city areas, and energy conservation. His emphasis on the socially inclusive and environmentally friendly potential of public transportation culminates, within the range of the KTLA collection, in his July 1980 announcement of a major new “multi-modal” transport hub centered on Union Station. Speaking alongside Governor Jerry Brown, he defends transit riders from a skeptical journalist who labels them “a special interest group” and he passionately describes Union Station as “one of the gems in the passenger transportation system of the United States [and] one of the architectural landmarks in the city of Los Angeles”. That clip typifies Bradley’s insistence on a coordinated municipal, regional, federal, and international approach to the city's challenges and opportunities—several clips refer to the connections of Los Angeles with other Californian cities and with Washington, D.C., while others recognize its links abroad—for example, with Israel and China. In a complex and multi-layered world, as Bradley sees it, L.A.’s role is increasingly to lead and show the way, and he frequently uses aspirational language to emphasize the city’s innovation and influence on others, claiming L.A.’s transportation plans are “in the forefront of the cities of this country,” arguing that in the future “Southern California and Los Angeles will be foremost” in trading with China, and underlining his support for school desegregation by citing his belief in the “greatness” of Los Angeles and its people in the face of earthquakes, fires, and other crises.

His emphasis on the socially inclusive and environmentally friendly potential of public transportation culminates, within the range of the KTLA collection, in his July 1980 announcement of a major new “multi-modal” transport hub centered on Union Station. Speaking alongside Governor Jerry Brown, he defends transit riders from a skeptical journalist who labels them “a special interest group” and he passionately describes Union Station as “one of the gems in the passenger transportation system of the United States [and] one of the architectural landmarks in the city of Los Angeles”. That clip typifies Bradley’s insistence on a coordinated municipal, regional, federal, and international approach to the city's challenges and opportunities—several clips refer to the connections of Los Angeles with other Californian cities and with Washington, D.C., while others recognize its links abroad—for example, with Israel and China. In a complex and multi-layered world, as Bradley sees it, L.A.’s role is increasingly to lead and show the way, and he frequently uses aspirational language to emphasize the city’s innovation and influence on others, claiming L.A.’s transportation plans are “in the forefront of the cities of this country,” arguing that in the future “Southern California and Los Angeles will be foremost” in trading with China, and underlining his support for school desegregation by citing his belief in the “greatness” of Los Angeles and its people in the face of earthquakes, fires, and other crises.

While Bradley remains much admired, critics of some of his policies may find support in the KTLA collection for their view that he over-emphasized globalized trade at the expense of the poorest communities in L.A.—for example, only a few clips refer to L.A.’s lack of public housing and even then only briefly.2 On balance, though, the archive shows the remarkable perseverance of a progressive mayor, in an often remarkably progressive city, achieving, or at least aiming for, meaningful and fairly-distributed political, social, and economic change and opportunity. This is even more notable given the austere fiscal conditions of the 1970s, which Bradley recognizes frequently, and which culminate in the “drastic cuts” he is forced to announce by the passage of the conservative anti-tax measure known as Proposition 13 in June 1978, which decimated the city’s revenues. In one striking but somber clip, Bradley, full of regret, explains that the city’s budget will henceforth be cut by one quarter, up to 8,000 city workers will be laid off, and numerous public services will be curtailed, while City Council members listen in disbelief, slumped and depressed in their seats.

In short, the KTLA collection offers us an alternately inspiring and sobering snapshot of a fascinating city, era, and political leader. In doing so, it demonstrates the vitality and value of television newsfilm as a public historical resource. Indeed, in addition to representing Bradley and the politics of L.A., the archive is an important record of some of the inner workings of news reporting in what, in retrospect, seems like a heyday. Clearly, local television news played a key role in documenting, interpreting, and informing the city’s constant crises and innovation, contributing to Angelenos’ sense of place then just as the archive can do today. It shows us the techniques and technology of a certain kind of journalism—sometimes banks of cameras, tape recorders, microphones, lights, and cables set up for large press conferences in a formulaic way, but sometimes just one camera and reporter capturing remarkably vibrant footage of everyday life on the streets. Importantly, the KTLA collection contains not edited and polished news reports as they were broadcast but the raw newsfilm on which they relied, so much of what we see is quite improvised. For example, a shoulder-mounted camera zooming in on a child’s doll amid the burned out ruins of the SLA hideout in Compton, or the hubbub of parents and children excitedly boarding an Amtrak train at Union Station. Many clips contain technical ‘imperfections’ such as shots momentarily out of focus, lens flares, or sudden interruptions, but these only add to their immediacy, emotional affect, and human energy.

The 10 years of clips represented, from 1971 to 1980, also show the passage of time, as film cameras give way to video cameras, power suits displace flared jeans and robes, and long locks and Afros concede to short sideburns and perms. Over time, one also sees increasing diversity: just as one of Bradley’s key achievements was to increase the employment of women and people of color by the City of Los Angeles, so too do the ranks of KTLA reporters become more inclusive, as then household names Dick Garten and Stan Chambers, who joined the station in the late 1940s, are joined by Mike Botula, Jan Mitagawa, Carlos Aguilar, Tony Valdez, and Dixie Whatley. Indeed, in historical terms, the 1970s are now closer to World War II than they are to us today. Many clips feature cigarettes, smoke-filled meeting rooms, and all manner of behaviors and speech no longer quite so common. For example, Sam Yorty pronouncing “Los Angeles” with a hard “g” as many people used to do. This is not to indulge nostalgia, although the clips allow it; rather, it is to underline the rich humanity of these newsfilms and the society they depict, and to remind us of their role in the formation of the Los Angeles we know today.

Access more than 70 KTLA news stories featuring Tom Bradley on the Archive website.

About the author

Mark Shiel is Reader (Associate Professor) in Film Studies and Urbanism at King’s College London. He is the author of Hollywood Cinema and the Real Los Angeles (Reaktion Books/University of Chicago Press, 2012) and Italian Neorealism: Rebuilding the Cinematic City After World War Two, (Wallflower Press/Columbia University Press, 2006); he is the editor of Architectures of Revolt: The Cinematic City circa 1968 (Temple University Press, 2018) and co-editor of Screening the City (Verso, 2003) and Cinema and the City: Film and Urban Societies in a Global Context (Blackwell, 2001).

Notes

1. On Hollywood’s role in L.A.’s urban profile, see Mark Shiel, Hollywood Cinema and the Real Los Angeles, Reaktion Books/University of Chicago Press, 2012, and on L.A. and cinema in the 1960s, see Shiel, “‘It’s a Big Garage’: Cinematic Images of Los Angeles circa 1968,” in Architectures of Revolt: The Cinematic City circa 1968, Temple University Press, 2018, pp. 164-88.

2. For evaluations of Bradley’s legacy, see, for example, Mike Davis, City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles, Verso, 2006 (1990); Josh Sides, L.A. City Limits: African American Los Angeles from the Great Depression to the Present, University of California Press, 2004; and John Laslett, Sunshine Was Never Enough: Los Angeles Workers, 1880-2010, University of California Press, 2016. Several commentators on Bradley’s tenure as mayor differentiate between an early “progressive” phase and a later “pro-business” phase – essentially, the 1970s and 1980s, respectively. See Joao H. Costa Vargas, Catching Hell in the City of Angels: Life and Meanings of Blackness in South Central Los Angeles, University of Minnesota Press, 2006, pp.43-4.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation