Les Misérables (1925-26)

I first started attending Le Giornate del Cinema Muto (“Days of Silent Film,” also known as the Pordenone Silent Film Festival) in 1988, when the festival was in its seventh year. I was invited to accept the annual Jean Mitry Award in the name of George Pratt, the former curator at George Eastman Museum who had died in May of that year. A tradition that began in 1986, this year’s award was presented to Adrienne Mancia and Lenny Borger. The solid week of silent cinema, screening from 9 a.m. until after midnight, was attended by an international assortment of film historians and archivists, as well as the local Italian community in this provincial town that is just north of Venice. Indeed, the festival started in 1982 after a devastating earthquake in Friuli, as a way of giving relief to its victims. I became a regular. And while I have missed none too few Giornate, I’m always delighted to return, as I did for this year’s festival (October 3-11).

In the first decades of the Giornate, the program was often dedicated to a single theme or national film production (e.g. pre-revolutionary Russian cinema or German film before Caligari), but since the turn of the century the festival has broadened its scope by presenting a variety of programs. The 34th festival was dedicated to, among other things, Victor Fleming, Russian Soviet comedies, Bert Williams, city symphonies, Italian musclemen in German cinema, Latin America, the beginnings of the western (pre-WWI), the canon revisited, rediscoveries and restorations, and a host of special events. Given my late arrival and commitments to meet many of my FIAF colleagues who now regularly attend the Giornate, I was not able to see everything the week had to offer, but there were definite highlights.

Les Misérables (1925-26)

Without a doubt, the major discovery this year was Henri Fescourt’s four-part epic, Les Misérables (1925-26), which blew everyone away, despite its more than six and a half hour length, shown in one sitting with a dinner break. Now the conventional wisdom on French commercial cinema has always been that it had gone into decline during WWI, after dominating world cinema, including the American market, only to recover in the early sound period with René Clair and Jean Renoir. The popular filmed novels of the 1920s had an especially bad reputation among French cinephiles, like Louis Delluc, who championed their own avant-garde. As a result, many at the festival were dreading the lengthy endurance test. Much to everyone’s surprise, this dramatization of Victor Hugo’s sprawling 19th-century novel almost flew by, a work of such visual, philosophical and moral power that it must now be considered the most successful adaptation of the more than 50 filmed versions.

Les Misérables (1925-26). (Image credit: Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé).

Starring Gabriel Gabrio as Jean Valjean, the ex-convict who overcomes his brutalizing youth to become a mensch, the film’s mise-en-scène is both exceedingly naturalistic and at times fantastic, framed in brilliant color tinting, toning and mordanting, all made possible through a digital restoration by the Centre national du cinéma et de l’image animée (CNC) at Bois d’Arcy with materials from La Cinémathèque de Toulouse and Pathé. Fescourt shot the film in southern France and in the medieval town of Montreuil, offering amazing views of a long-lost French countryside. The Paris scenes in the film’s final part were shot in a studio, based on Gustave Brion’s illustrations for the first edition of the novel. The film’s power lies in its images. Fescourt and his longtime scriptwriter Jean-Louis Bouquet noted in an essay “L’idée et l’écran: Opinions sur le cinéma”: “The cinematic image is able to signify. Movement exerts a transformation of meaning as well as a plastic transformation” (trans. Richard Abel, French Film Theory and Criticism 1907-1929, p. 384). Scrupulously avoiding stereotypes, Fescourt creates characters of astonishing ambiguity, even when in the case of Javert they represent concept. One of my favorite characters was Éponine (sublimely played by Suzanne Nivette), the doomed daughter of the thoroughly corrupt Thénardier; her anguished features express both her love for Marius and the painful awareness of her evil origins. Everyone left the Verdi Theatre understanding that film history had been rewritten.

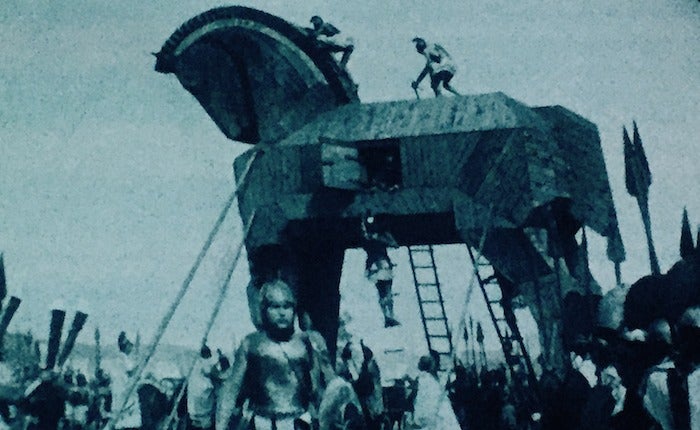

Helena – Der Untergang Trojas (1924)

Multi-part films were a bit of a thing this year, so too with the Munich Film Museum’s digital restoration of Helena – Der Untergang Trojas (1924), a two-part, three and a half hour-long epic, based on Homer’s The Iliad. Directed by Manfred Noa, who had previously made Nathan der Weise (1922), the film focuses on the events leading up to the abduction of Helen by Paris in its first part, and the destruction of Troy in the second part, the latter clearly blamed on the hubris of Priam. Featuring some of the greatest actors of the German stage at that time, including Albert Bassermann, Albert Steinrück and Adele Sandrock, with a script by German expressionist author Hans Kyser, Noa’s direction moves effortlessly from the intimate to the epic, while visualizing the utter brutality and violence of war. As with Les Misérables, digital technology has restored Helena’s original tinting and toning to great effect.

El automóvil gris (1919)

Finally, there was the three-part, nearly four hour-long Mexican crime serial (originally 12 chapters), El automóvil gris (1919), directed by Enrique Rosas. Strongly influenced by Louis Feulliade’s Fantômas (1913), the film tells of a criminal gang that terrorizes the Mexican bourgeoisie, apparently with the help of some high ranking military official who supplies uniforms and warrants, allowing the gang to gain entrance into the homes of the well-heeled. Shot in real locations (like Fantômas), the film seemed a metaphor for the chaos of the Mexican Revolution. It also seemed strangely contemporary in its view of a society overwhelmed by continual, senseless violence, where the lines between criminal conspiracy and government corruption are free-flowing at best.

Had I only seen these three films, the trip to Pordenone would have been worth it.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation