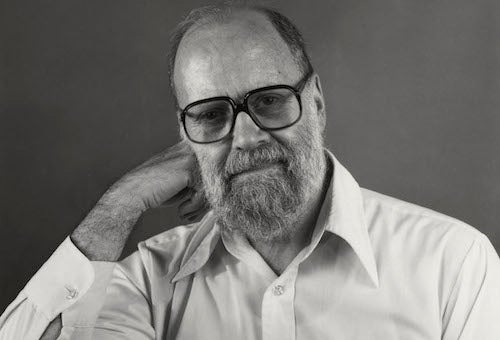

George Pratt worked in the Film Department at George Eastman House. He was my colleague, editor, advisor and friend. George was also my mentor, as he was to other striving, young film historians and curators. George worked quietly and diligently, collecting materials, saving bits of data, which back then seemed important to only a few isolated pioneers. For all those who came to do research at Eastman House, or wrote to him, George opened his files, generously, humbly, completely.

George was born in La Grange, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago, on September 14, 1914. His life before World War II is a bit of a mystery, but I do know he was a film buff who remembered watching silent films. In 1947 he was working in a large record store in the Loop in downtown Chicago when he co-founded the Roosevelt College Film Society, which screened films on Michigan Ave. For six years, George programmed their film series and wrote all the program notes, presumably as a volunteer, since he continued to work his day job. George was never interested in money, but rather in an ideal: a community of scholars and cinephiles dedicated to the preservation of film culture. It was the age before the professionalization of film studies, before the politics of academia governed the dissemination of film knowledge.

Late in 1953, George moved to Rochester, NY to accept a position at Eastman House as assistant to the Curator of Film, James Card -- himself a legendary collector. At the time, George was corresponding regularly with Card, culling film credits and other filmographic data on films in the Eastman collection from the pages of The New York Dramatic Mirror, which he accessed at the Chicago Public Library. His first salary was well under $70 a week and for nearly 20 years afterwards, his salary remained at a shamelessly low level. At some point, he and Card had a falling out, possibly due to Louise Brooks, who became George’s friend after Card ended his affair with the actress. In any case, they worked side-by-side without talking to each other for the rest of their careers.

George brought to Eastman House a number of important film stills, scripts and paper collections, viewing these pieces of film ephemera as important primary documents for a history of cinema ... Through his work and writings, George educated a whole new generation of film historians in the use of primary source material.

Meanwhile, George continued his filmographic research, cataloging and documenting not only the film collections. Apart from his documentation activities, George brought to Eastman House a number of important film stills, scripts and paper collections, viewing these pieces of film ephemera as important primary documents for a history of cinema. At the time, it must be remembered, few film historians made use of such materials. Film historical writing was still being done from memory, from having seen the films. Through his work and writings, George educated a whole new generation of film historians in the use of primary source material. I remember when I was a post-graduate museum intern in the mid-1970s, George patiently guided me through the maze of files, books, film magazines and photographs. We would begin with a particular filmographic problem and then, as if on some grand treasure hunt, ferret out all the relevant information, often times resolving an issue after flipping through one of George's legendary notebooks. In these loose-leaf binders, ordered according to film companies, George patiently noted by hand any bit of information he had culled from trade periodicals like The Moving Picture World. George also continued to publish numerous articles in Image, Eastman House’s journal, becoming its editor from 1972 to 1980. It was during this period that he published my own first attempts at film history, thus encouraging a young post-graduate to continue in the field.

memory, from having seen the films. Through his work and writings, George educated a whole new generation of film historians in the use of primary source material. I remember when I was a post-graduate museum intern in the mid-1970s, George patiently guided me through the maze of files, books, film magazines and photographs. We would begin with a particular filmographic problem and then, as if on some grand treasure hunt, ferret out all the relevant information, often times resolving an issue after flipping through one of George's legendary notebooks. In these loose-leaf binders, ordered according to film companies, George patiently noted by hand any bit of information he had culled from trade periodicals like The Moving Picture World. George also continued to publish numerous articles in Image, Eastman House’s journal, becoming its editor from 1972 to 1980. It was during this period that he published my own first attempts at film history, thus encouraging a young post-graduate to continue in the field.

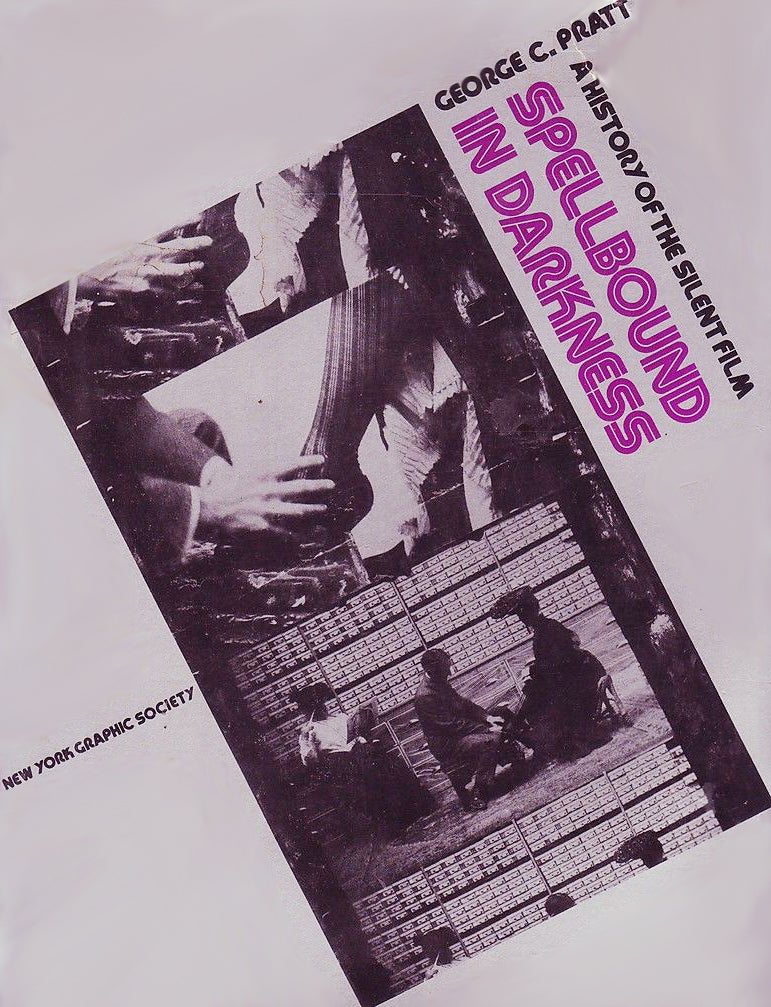

In the late 1960s, George, who had been promoted to Assistant Curator, completed his magnum opus Spellbound in Darkness: A History of the Silent Film. First published in mimeograph as a teaching aid for his film history students at the University of Rochester, the New York Graphic Society picked it up for hardback publication. The work comprised a history of silent cinema from its beginnings to its demise, as documented in contemporaneous sources, including magazines, film journals, newspapers and non-fiction books. Although George states in his introduction, "My comments simply bind the chapters together," his remarks indeed constitute an intelligent, informative, highly original and self-reflexive history of silent cinema. George was always too modest. He never completed another book, although everyone had hoped he would publish his massive Thomas Ince research. His notebooks did become a major source for Elias Savada’s American Film Institute Catalogue of Motion Pictures Produced in the United States, 1911-1920.

In 1984, I became George’s successor at Eastman House, and for the next several years we would do lunch at least once a week, during which he’d often advise me on institutional politics. George had a massive heart attack in the late 1970s and another one in early 1987. The last time I saw George was in the second week of May after he had already been in hospital for months. He asked me if he had done enough. I reassured him that he had. I then left for Europe to get married and go on my honeymoon in the South Indian Ocean. When we returned via Paris to attend the annual FIAF conference, I was told that George had died on May 22, 1988. That October, I travelled to the Giornate del Cinema Muto (Silent Film Festival) in Pordenone to accept in George’s name the Jean Mitry Prize for his “contribution to the reclamation and appreciation of silent cinema.”

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation