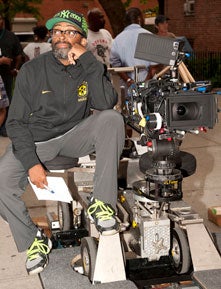

The past week’s reporting out of Sundance, surrounding Spike Lee’s comments at the premiere of his feature Red Hook Summer, has raised and rehearsed a number of familiar, fraught, but important conversations about media and race. The jumping-off point occurred when Lee, presenting his independent feature, voiced displeasure with Hollywood’s lack of support for Black cinema.

This sort of comment would not typically provoke much reaction at Sundance, whose raison d'être is presumably to fill the gap left by Hollywood’s myopia. The added question of race, however, and its vocalization by Mr. Lee, provoked a surprising flurry of opinions and counter-opinions in the blogosphere.

The conversations awakened by this incident, and given further, thoughtful consideration by Lee’s co-screenwriter James McBride, include the long debate over whether Lee is a champion or a malcontent, whether Hollywood owes more and better Black cinema to the public, or even to itself, and over what’s to be done about it.

Adding fuel to the fire, George Lucas, producer of Red Tails, recently mused that unless audiences supported his new film about Black WWII pilots, the cause of Black cinema might be set back for some considerable time. Comparisons have been drawn over the coverage that Lucas’ comments received in the press (where they were taken at face value) and the drubbing that Lee took, even by people of color. The public meta-commentary has sharpened accusations that a white establishment figure can say anything about Black cinema, while his Black counterpart is labeled a “complainer.“

The pivot point of Lee’s unhappiness reminds me of several observations made by film critic Robert Warshow. In his analysis of the gangster genre, Warshow began with certain observations about the American character:

“America, as a social and political organization, is committed to a cheerful view of life…. Happiness thus becomes the chief political issue—in a sense, the only political issue—and for that reason it can never be treated as an issue at all. If an American or a Russian is unhappy, it implies a certain reprobation of his society, and therefore, by a logic of which we can all recognize the necessity, it becomes an obligation of citizenship to be cheerful….

“But, whatever its effectiveness as a source of consolation and a means of pressure for maintaining ‘positive’ social attitudes, this optimism is fundamentally satisfying to no one, not even to those who would be most disoriented without its support. Even within the area of mass culture, there always exists a current of opposition, seeking to express by whatever means are available to it that sense of desperation and inevitable failure which optimism itself helps to create.”

Warshow highlights an American repugnance for the American who is not happy. This can easily be applied to the “character” that Lee plays on the American stage: not a genre gangster, by any means, but a man who generally declines to say “thank you”—for conditions he finds deplorable—in his narrative constructions and in his view of Hollywood. But if Lee were better satisfied with the status quo, or more diplomatic about the whole thing, it wouldn’t make it any less true that many people find much to be desired in the American entertainment establishment, insofar as it implicitly constructs a portrait of American experience and ethics, and of the American psyche, that excludes the interests of broad swaths of the population. Women, people of color, gender minorities and others confront a cinema that often elides the contributions of diverse populations in favor of a white and optimistic version of things. Even feature films that are most critical of industry and government usually put the problem down to a few “bad apples” gaming the system. The system is all right in the movies.

On the other hand, Hollywood’s firmer embrace of Lee wouldn’t necessarily represent a wholesale opening to Black cinema, either. Black cinema is more than Spike Lee. Also woefully absent from Hollywood’s rolls (and screens) are Julie Dash and Charles Burnett (to give just two examples), whose independent, international and television projects have been highly acclaimed. Notable also is Haile Gerima, whose long career on the international scene—notwithstanding his base in the U.S.—stands in determined opposition to Hollywood trappings and assumptions. Certainly the machine has shown Lee its indifference from time to time. But Lee’s long-standing, if sometimes embattled, centrality in the Hollywood establishment has also made him a necessary figure within the very system he decries, meeting a market need and symbolically proving the system’s flexibility.

It should thus be unsurprising that Lee finds Hollywood heedless to certain Black concerns, but equally disappointing is the slowness of American mainstream cinema to accommodate Black voices and stories, especially those that express outright dissatisfaction, without punishing or rehabilitating their protagonists. Perhaps more noteworthy is Lee’s long survival in the “role” of American gadfly, and the near-uniqueness of his position as a public scold in the cause of Black cinema. Is it a self-serving role? It has also served the cause of Black film, which might not have been enriched by Mr. Lee’s gifts without also a healthy dose of grit.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation

Comments