"Through brotherhood and family and togetherness we shall progress and succeed," explains Walter Gordon of his self-chosen Swahili name, Jamaa Fanaka. Names carry great implied meaning, and Fanaka lived up to his chosen name in his life and career by building family success, and advocating for racial equity in the film and television industry.

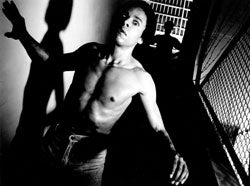

A word is a powerful concept. The name of his second film, Penitentiary conjures images of abuse, violence and anger. After being falsely convicted of killing a white biker, Martel Gordone "Too Sweet,” finds himself fighting for his life and his dignity in the penitentiary. Although witnessing the brutality of an unjust prison system on screen is horrific, Fanaka intended to use this film as a warning to those who would make wrong choices. "It was meant as a cautionary tale about how people can become institutionalized to where the prison is their home," explains Fanaka, "and they begin to think, 'You are not locked up. The rest of the world is locked out.'"

His brutal portrayal of prison life led some critics to link Penitentiary with the burgeoning prison industry, but Fanaka states, "a lot of people thought I was making a statement on the fact that there are a lot of Black inmates in prison. […] but, here's what happened, […] everybody in there, even the extras, were friends of mine or friends of friends of mine. […]So, all our friends where Black. I wish I had more whites in the film, but I could count on the Blacks showing up.” Fanaka may have found the inspiration for the film in his own roots.

As a young boy, Fanaka admired his cousin who would fight anyone to protect him, showing him an unconditional love that was different from his parents. She was not afraid of anyone and could best older boys in fights. When Fanaka was a young man he planned to rob a local drug dealer to get money to buy a car from his sex trafficking friend. He rationalized, “we felt that we were doing no wrong [...] we were taking money from people who were destroying our neighborhood.” He was dissuaded from his criminal intentions by “a sign across the street in a storefront in yellow and gold UCLA colors. It said, "UCLA! You are Welcome!" Over donuts and coffee, Fanaka decided to forgo the robbery for the chance to complete the undergraduate work he needed in order to be admitted to UCLA and the rest is history.

Fanaka never forgot the impact that experience had on him and he remains a supporter of Affirmative Action programs such as the one that placed UCLA outreach in his neighborhood in Compton. During his career he challenged the Directors Guild of America in court to honor Article 15.201 that required producers to increase the number of working women and minority directors, and requires them to submit statements documenting their efforts and success with the program. He also established the African American Steering Committee of the Director’s Guild of America to support Black filmmakers. Fanaka did not benefit from his actions, but he is happy to see other filmmakers benefiting from his activism. After his experience navigating the film industry, Fanaka wants to see Black filmmakers “Support each other’s efforts […] the way you’re going to get a lot more accomplished if you stick together than if you isolate. Of the comparison between the L.A. Rebellion and the Slave Rebellion he says “Yeah, I love that—the juxtaposition of those two things,” but “I know that you cannot expect that which you are not willing to give. And I’m willing to give and respect the works of any and the beliefs and the wherewithal of all races and creeds.”

Penitentiary cost about $100,000 to make and grossed $72,000 opening weekend. Fanaka went on to write and direct Penitentiary II and Penitentiary III and is currently working on Penitentiary IV.

—Dawn Spinella and Dalena Hunter

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation

Comments