The Twilight Zone

Looking for your next at-home movie / TV fix? Each week, our staff will offer their recommendations for international films and TV shows, old and new, classic and obscure, all available online through streaming platforms. The Billy Wilder Theater may be temporarily closed, but we can continue to watch movies together while practicing safe distancing at home. Share your #SaferAtHomeCinema thoughts with us on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook, and subscribe to our email list to receive updates!

For this edition, our Archivists Mark Quigley and Todd Wiener and Film Programmers Paul Malcolm and KJ Relth have selected titles around a subject we know too well: movie obsession.

The Twilight Zone: “The Sixteen-Millimeter Shrine” (dir. Mitchell Leisen, CBS, 10/23/1959)

Mark Quigley, the John H. Mitchell Television Archivist: With a direct nod to Sunset Boulevard (1950), writer Rod Serling conjures a wistful tale of a forgotten Hollywood star, Barbara Jean Trenton (a perfectly cast Ida Lupino), yearning to return to her glorious celluloid past. Isolated with a 16mm projector and an armoire full of prints, Trenton desperately seeks escape by obsessively screening her greatest films—to a point beyond madness. An impeccable work of anthology television, the teleplay is a showcase for Lupino, director Mitchell Leisen (Remember the Night) and composer Franz Waxman (who also scored Sunset Boulevard). Noteworthy for the screen-obsessed: the supremely-talented Lupino owns the distinction of being the only person to both star in and direct an episode (“The Masks”) of the beloved original Twilight Zone series. Streaming on Netflix and Hulu.

The Twilight Zone

It's a Great Feeling (dir. David Butler, 1949)

Todd Wiener, Motion Picture Archivist: Hunkering down for pandemic self-care probably means I reach for a musical; preferably one with the infectiously charming Doris Day. Day’s third film contains the Technicolor gleam, broad humor and lovely songs typical of her early career, but it is the hilarious tongue-and-cheek industry savviness and self-lampooning that Warner Bros. unleashes on itself that makes this film such a hoot. Day plays a waitress at the studio’s commissary that is desperate to break into the biz. A veritable WB cast-of-thousands, including auteurs Michael Curtiz, Raoul Walsh, King Vidor, etc., are trotted out for behind-the-scenes studio hijinks. With a runtime of only 85 minutes, this delightful industry roast is a perfect distraction as well as a love letter to one of the movie industry’s greatest backlots. Available for rental on Amazon and Apple TV.

It's a Great Feeling

The Day of the Locust (dir. John Schlesinger, 1975)

Paul Malcolm, Film Programmer: The creative team behind Midnight Cowboy (1969), director John Schlesinger, producer Jerome Hellman and screenwriter Waldo Scott, reunited for this scorched earth dissection of Hollywood. Based on Nathaniel West’s novel and set in the 1930s, the film opens on an idyllic Los Angeles scene, sunlight glinting in the sprinkler spray outside cozy bungalow court apartments. The denizens of the court are either hungry aspirants to fame—including a scenic artist newly arrived from the Ivy League (William Artherton) and a tragically self-absorbed starlet (Karen Black)—or the grizzled husks that remain when ambition fails (Burgess Meredith’s crumpled vaudevillian is a particularly pathetic example). Following West, Schlesinger and Scott survey the city’s pleasures and discontents with ethnographic purpose from Hollywood’s elites to its hangers-on and the liminal zones—brothels, cockfights—where they meet. Donald Sutherland delivers the film’s most mesmerizing performance as a tightly-wound, evangelical accountant, the stunned and stunted face of the middle class. Lurking at the edges of it all are the true moths to the flame, nameless tourists and autograph hounds consumed by their obsession with Hollywood spectacle. In the film’s climactic sequence, their frustrated desires explode in an operatic frenzy before a Mann’s Chinese Theatre recreated entirely on a Paramount sound stage. As a movie about movie making, Locust was itself shot almost entirely in studio—it’s a bravura work of production design (Richard Macdonald) and lighting (Conrad Hall)—which only underscores the Dream Factory’s power: even when its artifice is laid bare, its images can still seduce. Available for rental on Amazon.

The Day of the Locust

Peeping Tom (dir. Michael Powell, 1960)

KJ Relth, Film Programmer: Is there a single motion picture that more hauntingly illustrates the pleasures and pains of scoptophilia than Michael Powell’s still-underappreciated horror-thriller? Perfectly executed in eye-popping Eastmancolor from its leering, first-person point-of-view opening sequence, Peeping Tom draws out that intrinsic link between voyeurism and movie-watching so masterfully explored by Hitchcock (Rear Window comes to mind) to its chilling extreme. In our childlike, stoic, loner protagonist Mark Lewis, disquietingly portrayed by Austrian-German actor Carl Boehm, we unwittingly find an analog of self. As we sit transfixed on our screens, clamoring for that same authenticity Mark strives to capture with his camera, we recognize his obsession as a comfort, as a crutch, and, perhaps most disturbingly, as a weapon. Condemned for its moral bankruptcy upon its initial release, Peeping Tom was awarded cult status just a decade later and only seems to grow in relevancy. Film theorist Laura Mulvey, one of the first to critique the male gaze and erotic ways of looking in cinema, joined that chorus of reappraisals in the 1990s, understanding that Powell’s masterpiece “creates a magic space for its fiction somewhere between the camera’s lens and the projector’s beam of light on the screen.” Streaming for free (with ads) on Tubi.

Peeping Tom

Camera Buff (dir. Krzysztof Kieślowski, 1979)

Paul Malcolm: In preparation for the birth of his first child, a Polish factory worker, Filip (Jerzy Stuhr), spends two months’ pay on an 8mm camera to memorialize the quiet, contented home life that he’s always wanted and has finally achieved. Almost immediately, however, he becomes more intent on filming that life than actually living it. When his boss asks him to document his plant’s upcoming anniversary, Filip leaps from amateur to aspiring professional status and his cherished domestic world suddenly looks too small. As his wife grows discontented by this hobby-turned-obsession, his compulsion to film “everything that moves” earns him the enmity of local apparatchiks and an unexpected celebrity among a coterie of intellectual critics and producers. Director Krzysztof Kieślowski was well-versed in the hypocrisy and absurdity of both groups having made documentaries for Polish television until this, his second fiction feature, brought him to international prominence. He and co-screenwriter Jerzy Stuhr draw sharp comedy from Stuhr’s big-eyed autodidact fumbling through hard lessons in aesthetics and politics, reality and representation, not to mention some sincerely touching moments about the power of film to connect us. The heart of the film lies in Filip’s struggle to learn from the former on his way to finding a means to the latter, that is, on his way to becoming an artist. Streaming on the Criterion Channel.

Camera Buff

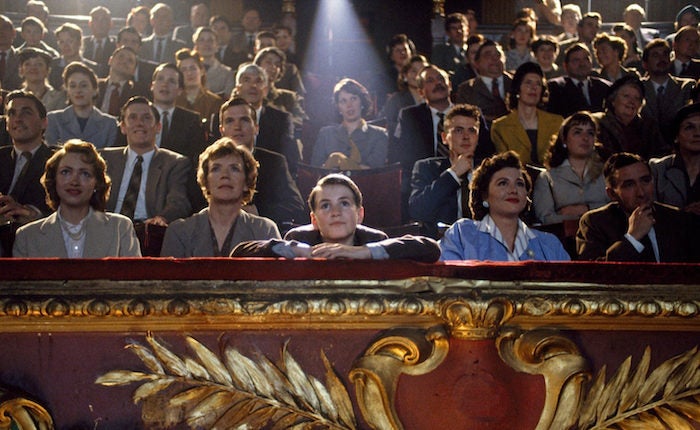

The Long Day Closes (dir. Terence Davies, 1992)

KJ Relth: Attempting to describe the plot of Davies’ simple, affecting treasure is as foolhardy as recalling a dream. Its inclusion this week is as much for leading lad Bud’s own obsession with moviegoing as for the soaring wave of cinephilia it churns and reinforces so profoundly within its spectator. With a soundtrack peppered with lines of dialogue from The Magnificent Ambersons and songs from Meet Me In St. Louis, Davies quilts together an autobiography of his 1950s Liverpudlian childhood from moments of admiration for light: its qualities, its possibilities, its ability to mark the passage of time, and its unique form as a vehicle to deliver a cinematic story. The ideal way to watch this film, as prescribed by a dear friend upon my recent home viewing, is as follows: turn all the lights off, shutter all the windows, and turn up the volume. I might add, “and put your phone away.” Emulating this at-home cinematic experience is perhaps the closest we can come during these isolated times to that unique comfort of settling into a theater seat enveloped by darkness and sound. Watching The Long Day Closes, you might just begin to recall what it’s like to share that space with fellow cinema patrons, united in the communal pleasure of visual and sonic elation. Streaming on the Criterion Channel.

The Long Day Closes

< Back to the Archive Blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation