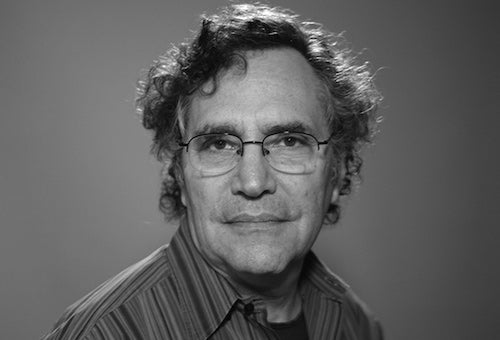

Founded in 1966, the Chicago-based nonprofit Kartemquin Films has championed documentary filmmaking for 50 years, capturing deeply human stories while chronicling larger social, political and economic issues. The organization has also worked to democratize film production by serving as a resource and collaborative community for emerging nonfiction filmmakers. UCLA Film & Television Archive celebrates this milestone with Kartemquin Films at 50, a selection of titles that will screen at the Billy Wilder Theater in Los Angeles from September 16-26. We interviewed Kartemquin co-founder and artistic director Gordon Quinn, who will be on hand for this retrospective:

Kartemquin emerged in 1966 amid incredible political and social upheaval. How did that ethos shape your work, the collective and its mission?

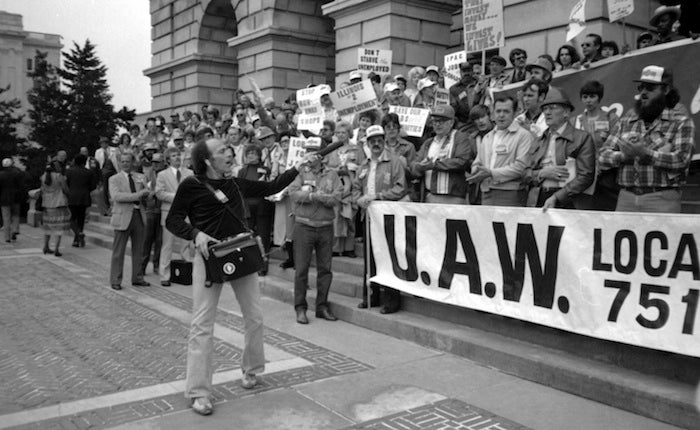

Initially we thought that cinéma vérité would be enough. To be able to reflect society back on itself, we thought, could lead to social change. But, as you say, it was the sixties and we soon realized that we had to deal with power relationships if we are going to really engage in social change. The collective emerged organically from the times people started coming around the studio. Suzanne Davenport and Jenny Rohrer, who were active in The Chicago Womens Liberation Union, brought in what became The Chicago Maternity Center Story project in 1970-71, and that was really the beginning of the collective period at Kartemquin. Jerry Blumenthal and I were developing films around labor issues (Taylor Chain, The Last Pullman Car) and people joined from that movement, and others like Peter Kuttner came with projects from organizing youth (Trick Bag). Media activists like Judy Hoffman and others people who had been involved in Chicago Newsreel joined. We were shaped by the values of these various organizations and movements. The collective lasted until around 1978. But a lot of the things we implemented in that period, particularly the focus on skill-sharing and mentorship, are part of the ethos today.

Jerry Blumenthal recording audio for The Last Pullman Car, 1981. All images courtesy of Kartemquin Films.

What do you think makes documentary filmmaking a particularly effective instrument for democracy and social change?

In recording life as it unfolds you're providing people with a common experience. They all see the same thing. They may not interpret it the same way and they may look at the film and see different details or focus on different things but there's this sense of having experienced something together. In a democracy those common experiences are important. The details of daily life are important. Seeing other people in society of whom we may not have intimate knowledge, seeing their lives in the way we present them in our films can lead to fundamental change in terms of how people view each other. There is a specificity, a density, to the film image that challenges people to draw their own conclusions at the same time that it may be shifting their beliefs. However film does not, in and of itself, make social change. Film moving people to get organized and take action is what makes change.

Gordon Quinn, 1967

The opening night film, Raising Bertie, is an ambitious work that spans six years and tackles such critical but often overlooked issues as poverty, education and the African-American experience in rural America. How did this project come together? And more generally, how does Kartemquin choose its projects?

This is a great example of what I was talking about in the previous question. When Margaret Byrne brought the project to Kartemquin we saw the potential for a film about a rural part of the country and young men coming of age whose stories are just not told in our society. Her approach of telling their story with all of the drama, complexity, and concreteness of life, all of the success and failures that make up life, meant that she was going for an organic story that respected her characters and was not going to reduce them to a sound bite or an inspirational story arc. The film is something for the whole nation to reckon with, but it plays especially well in Bertie County, where the people who have seen it are saying, “Yes, that is our story.” County elected officials have participated in outreach events and are already talking about making change based on what they saw in the film. That’s a big early victory for the filmmakers, who aren’t from there, and it’s a rare one in documentary. More generally, we are looking to be approached by driven filmmakers, like Margaret, who are passionate about the story they want to tell, and are also looking for what Kartemquin offers, which is a collaborative community. We look at the values of the filmmaker and their commitment to collaboration as much as we do subject matter of a project. We care about relationships that are going to last for years, maybe all our working lives, not just a single film. And it needs to be someone who is determined but also seeking that dialectic engagement with us about their choices they are making as they construct their film. At the end of the day they make the film they want to make, we don’t tell them what to do, but we hope to guide them to make it a stronger work than they might have been able to make on their own.

Raising Bertie (dir. Margaret Byrne, 2016)

Films that are independently produced or made on a modest budget are often at risk of disappearing from public view. How has Kartemquin dealt with the challenges of preservation, so that its body of work can be seen by future generations?

It is a constant struggle. For our 50th Anniversary we have been featuring screenings in public, on TV and online of some of our oldest films like The Inquiring Nuns, Winnie Wright, Age 11, and Now We Live on Clifton, and have been amazed by how well they play today and the dialogues they provoke. I knew from the start how important it was to save everything, but with no resources… well I don’t like to think about what has been lost over the years, but now with support from foundations like the Donnelly Foundation and Logan Foundation we have a robust archiving project and a great database that catalogs everything we have. The next step is preserving it, and then making it available for presentation. We have got some grants from the National Film Preservation Foundation to preserve and restore past work. A Chicago organization, Media Burn, got funding from the National Endowment for the Arts to digitize and start putting online our early video work, including the raw unedited (outs) tapes. And we were fortunate that the Sundance Institute, UCLA Film & Television Archive, and the Academy Film Archive helped make a beautiful restoration of Hoop Dreams in its original aspect ratio in 2014. Now we are making sure that we are archiving the new films and digital assets to the best preservation standards we can afford. We still always need help in this, but we’re trying to set a good example.

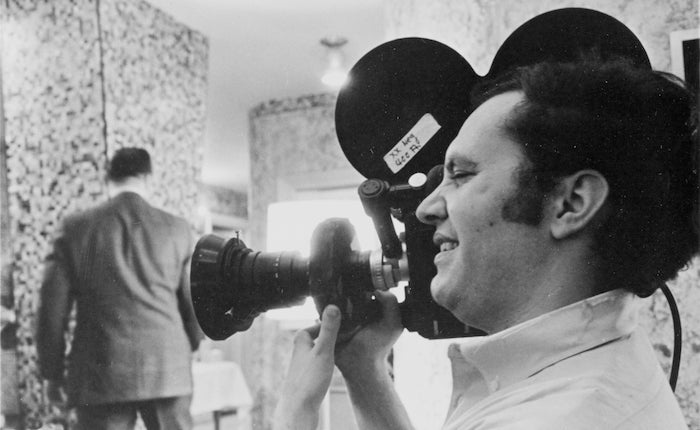

Inquiring Nuns (dir. Gordon Quinn, Gerald Temane, 1968)

Looking back at Kartemquin’s remarkable 50-year history, what are some of its proudest moments?

Well you always feel special about your first film. I remember when we showed Home for Life to the staff of the old age home and they were so glad to see their work honored and that we actually dared to show what they do. Some people on the board of the home freaked because they wanted a film that was all hearts and roses, not real life. We had to stand up for the film, and the staff stood with us. Other moments, more recently, include receiving the 2015 IDA Career Achievement Award from Chaz Ebert and Haskell Wexler, and the moment in our 50th celebration this June in Chicago where we invited all of our subjects, filmmakers and partners from the past years on stage for a group photo, so many people who are Kartemquin together. I love seeing the participants in our Diverse Voices in Docs DVID program — which we do in partnership with the Community Film Workshop — graduate from the program. But really it is moments when I have been shooting: two vets who have returned to Vietnam alone in a hotel home finally open up to each other in front of the camera; an immigrant has just confronted her husband about some of her hopes and frustrations with her new home; and a painter tells us step by step about his creative process.

—Jennifer Rhee, Digital Content Manager

< Back to the Archive Blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation

Comments