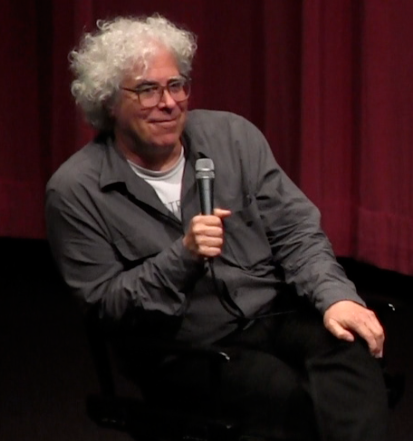

Two weeks ago, UCLA Film & Television Archive premiered Ron Mann’s latest documentary, Altman(2014), in our retrospective series on director Robert Altman, which included no less than 29 of his feature films and numerous hard to see shorts, industrial films and television programs. The film brought out a number of members of the Altman family, including Michael Altman (the director’s son), Sally Kellerman and René Auberjonois, as well as Ron Mann and his long time editor, Robert Kennedy.

I had not seen Ron Mann for at least 25 years, since presenting his first theatrical documentary, Comic Book Confidential(1988), at George Eastman House in Rochester, NY. That film had been nominated for a grand jury prize at Sundance and won 1st prize at the Chicago International Film Festival, before becoming a major commercial success. His next major documentary hit was Grass(1999), which was a partisan look at the American government’s war on marijuana and pot smokers, Mann being himself on the Board of NORML, the national organization to revise marijuana laws (as was Robert Altman, who famously admitted to smoking a joint every day of his life). Then, several years ago, Mann’s name kept turning up on my desk, because the Archive is the official repository for Altman’s work and Mann had signed a contract to make a film about the director, who passed away in 2006. Furthermore, the Archive agreed to help digitize many of the early shorts and industrial films that Altman had directed in Kansas City, but are now housed at the University of Wisconsin.

Mann’s Altman is an homage to Robert Altman, possibly the most important independent film director in America in the last quarter of the 20th century. The documentary illustrates the director’s life and work in Hollywood more or less chronologically with home movies, behind-the-scenes footage, “the making of” films, photos and film clips from his many works. While Ron Mann includes talking head interviews, these are shot in a uniform style in front of a black screen and kept extremely short, allowing his actors and co-workers to answer only one question: What is “Altmanesque”? The brief answers reveal the level of honor, respect, love and admiration Altman’s collaborators felt for the director. I was surprised to learn that Altman had been kicking around Hollywood as early as the late-1940s, before returning to Kansas City to direct industrial films, and then worked in American television for more than 12 years before directing his break-out M*A*S*H(1970).

I saw that M*A*S*H on a date the summer of my freshman year, when I was nothing but a normal film consumer, so I read M*A*S*H as an anti-Vietnam parable without being attuned to its revolutionary film technique. The film that really blew me away, having discovered film studies, was McCabe & Mrs. Miller(1971), which indicated to me that the counter-culture had invaded Hollywood—and not only because of its Leonard Cohen soundtrack. As would become Altman’s style, McCabe was a virtually plotless film, focusing instead on atmosphere and place, supported by Vilmos Zsigmond’s washed out cinematography. The scene where Keith Carradine, playing a country bumpkin, gets gunned down in cold blood by a gunslinger has stayed with me for decades, because Altman captures here the sheer banality and senselessness of death. This also applies to Warren Beatty’s fate in the snow.

The film that really blew me away, having discovered film studies, was McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971), which indicated to me that the counter-culture had invaded Hollywood.

In the 1970s, then, as I entered graduate film studies, Altman became one my favorite American film directors. I literally imbibed his subsequent films: Images (1972), The Long Goodbye(1973), Thieves Like Us(1974), California Split(1974) and Nashville(1975). Not that I always thought they were masterpieces. In notes I kept on every film I watched at the time, I wrote that Images captured the essence of schizophrenia by having the color cinematography appear virtually monochromatic in shades of grey and brown, thereby avoiding any cheap psychology of the character. But the play between reality and Cathryn’s (Susannah York) fantasy life left viewers confused. California Split visualized the pathology of gambling, but the two central characters were far from sympathetic. Indeed, Altman’s style is profoundly anti-psychological, observing the surface of things, creating specific descriptions of atmosphere and place, but also keeping characters at a distance. The lack of strong plots was not a handicap for The Long Goodbye where Raymond Chandler’s novel had an equally opaque story, but lots of sun-drenched, L.A. set pieces---or Nashville which is a masterpiece about a specific place and time.

However, it was no surprise when Altman fell out of favor at the end of the decade, because Hollywood had returned to chasing plot-heavy blockbusters in the mold of Star Wars. After that, Altman would reappear every few years with a comeback, such as The Player (1992)or Gosford Park(2001), but he never achieved the intense cultural currency of that ‘70s streak. Personally, though, I’ll never forget how he opened my eyes at a crucial moment in my own professional development.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation