Richard Nixon was my first pin-up.

It wasn’t so unlikely. My first years were spent in a smallish town in conservative Northern Oklahoma, a state that handed Nixon one of his highest margins of victory in the 1972 popular vote tally when I was nine years old. Young people were strong for Nixon that year, stronger than the George McGovern campaign had reckoned. Subjectively I recall a strong Nixon bias amongst the very young at Ponca City’s Washington Elementary School, where McGovern ran a distant second in playground debates that loosely associated him with both marijuana (a slander, it now seems) and cooties.

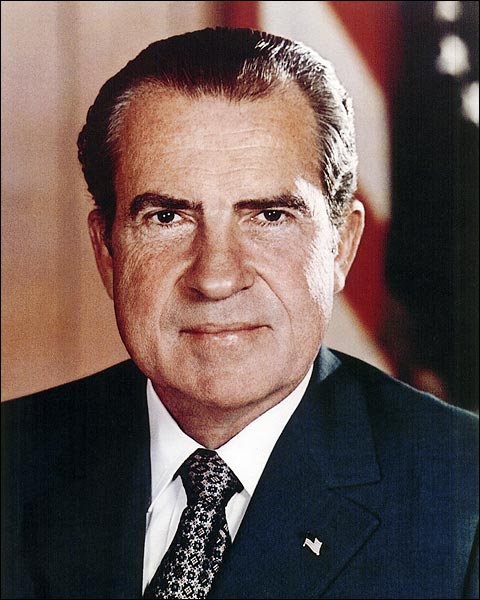

My father was a Federal government employee, whose workplace featured a large official portrait of the President. At my request a duplicate copy of this picture was found, and hung in my bedroom. The 37th President smiled benignly on my play for a considerable time, but mysteriously disappeared after many months of confusing “Watergate” talk on TV (and the playground). By the time of the President’s historic resignation, I recognized the depth of his public shaming, and reasoned that the man must be suffering. That others might have suffered as a result of his actions was a point lost on me. The child that I was wished to ease the man’s pain, and I managed to write and mail him a consoling letter. I'd like to have received a letter by return, letting me know that I needn’t stop looking to the Presidency for reassurance. No such reassurance came back.

As years passed, Nixon popped up occasionally on TV, seeming more ghostly each time. Still, it was expected that he would be interviewed occasionally. More surprising by far was that he became a subject of serious and ambitious artistic production, as in the Hollywood film All the President’s Men (1976), the opera Nixon in China (1987)—even the Oliver Stone feature biopic. They all seemed to suggest that his story was especially worth telling, and remembering—warily, and on terms other than the President’s own.

Less well-known, but essential to any commentary on Nixon’s lasting impact, is Robert Altman’s 1984 film of the one-man play Secret Honor by Donald Freed and Arnold M. Stone, screening this Saturday, May 17 at UCLA Film & Television Archive. In the film, a fictional Nixon, portrayed by Philip Baker Hall (who developed the character in the original play), spends 90 minutes in his private office, rehearsing an elaborate apologia into a vexing, hard-to-operate tape recorder, overseen by glowing video monitors that bespeak the presence of hidden, closed-circuit television cameras. Here was a Nixon more human and plausible than the smiling, composed portrait subject to which I had paid implicit respect day after day as a child. Here in fact was a speculative portrait that could have been recorded on the day my letter to the President might have arrived and been delivered to his wood-paneled, private office.

But Secret Honor is no movie for children.

Produced in the 10th year after Nixon’s great disgrace, unflinching in its moral condemnations while outlining the underlying emotional complexities of a troubled soul, the film suggests that the threat posed by a Nixon cannot be eradicated by his being jettisoned from public life. Rather, the film’s implicit narrative frame enlarges—even in the confines of a one-room set—to accommodate an unflattering, extended portrait of an American electorate that would support such a man and his politics so overwhelmingly. One of the play’s many achievements is to treat as an open question whether the jaundiced conclusions drawn by Nixon about his fellow Americans are indeed “true,” or simply an observation of the playwrights (and of course, Robert Altman—a progressive who nonetheless kept overt politics out of most of his work). An opening disclaimer makes clear that the fictional, speculative drama is a “political myth,” and indeed its haunting questions linger more than any Freudian “facts” ever should. Indeed, although the Freudian mother-complex is well developed in Secret Honor, it maintains its status as a poetic conceit, shining a light on the nexus of conviction and expediency that makes up leadership in its various colors. Besides all this, the things that the fictional Nixon claims to have done, secretly, make for a fascinating theory that packs a terrific dramatic punch.

Philip Baker Hall, indelibly haunting in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Hard Eight (1996) and Magnolia (1999), alongside numerous other arresting performances, confronts the epic challenge of this play with all the dead-seriousness and force required to unearth the Shakespearian promise within. By no means a dead ringer for Nixon, and rendering no dime-store Nixon impersonation, he brings to vivid life a fractured, paranoid, and no-less-brilliant-for-being-utterly-cynical former leader of the free world, a fallen statesman with virtually no one left hanging on his words, unless they be the words that will hang him. Indeed, the action of Secret Honor sees the fictional Nixon rehearsing a defense that he expects to present at some tribunal (presumably before having been pardoned by his successor, Gerald Ford). Because it’s a rehearsal, one guesses that by showtime, he will have tightened up his act, and no longer be laughing, growling, whimpering and (literally) barking as his mind chases down the tangents that brought him to such a moral abyss. Rare is the feature film that asks of an actor what Hall brings to this role: a cyclonic gathering of energies that re-define the confines of a single room. Rather, the space of the film is Hall’s body: contorted with emotional pain, arched with venomous hatred for his nemeses, plaintively searching the middle-distance with nostalgia in his eyes, or bounding across the room with glee, distracted by a stray happy memory.

Philip Baker Hall, indelibly haunting in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Hard Eight (1996) and Magnolia (1999), alongside numerous other arresting performances, confronts the epic challenge of this play with all the dead-seriousness and force required to unearth the Shakespearian promise within. By no means a dead ringer for Nixon, and rendering no dime-store Nixon impersonation, he brings to vivid life a fractured, paranoid, and no-less-brilliant-for-being-utterly-cynical former leader of the free world, a fallen statesman with virtually no one left hanging on his words, unless they be the words that will hang him. Indeed, the action of Secret Honor sees the fictional Nixon rehearsing a defense that he expects to present at some tribunal (presumably before having been pardoned by his successor, Gerald Ford). Because it’s a rehearsal, one guesses that by showtime, he will have tightened up his act, and no longer be laughing, growling, whimpering and (literally) barking as his mind chases down the tangents that brought him to such a moral abyss. Rare is the feature film that asks of an actor what Hall brings to this role: a cyclonic gathering of energies that re-define the confines of a single room. Rather, the space of the film is Hall’s body: contorted with emotional pain, arched with venomous hatred for his nemeses, plaintively searching the middle-distance with nostalgia in his eyes, or bounding across the room with glee, distracted by a stray happy memory.

Robert Altman saw Secret Honor staged in Los Angeles during a period when he had become intensively involved with live theater; directing occasional plays and bringing play adaptations to the large and small screens. It reflected an extension of an early involvement with theater in his native Kansas City, but was also a resourceful way to stay in motion when his star was considered to have fallen in Hollywood. Small productions, small distribution and big themes characterized this period of about five years, during which time Altman also undertook a visiting lectureship at the University of Michigan. It was with the infrastructure at that school, and the participation of The Los Angeles Actors’ Theater (original presenters of Secret Honor) that Altman got together the machinery necessary for a film of this kind. Special care was taken to coordinate the fictional space with the need for Hall to move through it freely, along with cameras and a film crew. In the balance, a relatively intimate space became the staging ground for riveting drama.

As an Altman project made “off the grid” (of Hollywood), Secret Honor emerged as probably the closest thing to an Altman triumph in this period. Writing in The New York Times, Vincent Canby greeted the film as a “cinematic tour de force,” noting not only the surprising performance of Hall, but also singling out Altman who “serves [the material] beautifully,” creating a “fascinating, funny, offbeat movie.”

Even with as much bile as the play reveals, it also affords a complete catharsis—which of course is not the same as a happy ending. Rather, one comes out of the film having been offered a viable working theory of power that corrupts absolutely; not impersonal power, but over-large, and threaded with hopes, allegiances, compromises, deferred promises and rewards, and of course, crushing disillusionment. In this way, it’s a work of truths about human nature and foibles; of things that might happen to you or me (by extension) if we don’t watch out—and not necessarily of “facts” about Richard Nixon. As portraiture, it joins such celebrated works as Velázquez’ 17th-century rendering of Pope Innocent X, famed for the roughness and ruddiness of its surface and the searching look in the eyes of its subject, who is supposed to have said of it: “all too true”… and then hid the portrait away in his family home. Such immediate, evocative and qualified “truths,” more the province of art than science, are of particular use when trying to get all the way around such an outsized figure as Nixon. And a portrait that deals in as many dimensions as Secret Honor is a worthy replacement for the earlier one—oblique, generalized and reassuring—that has been lost.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation