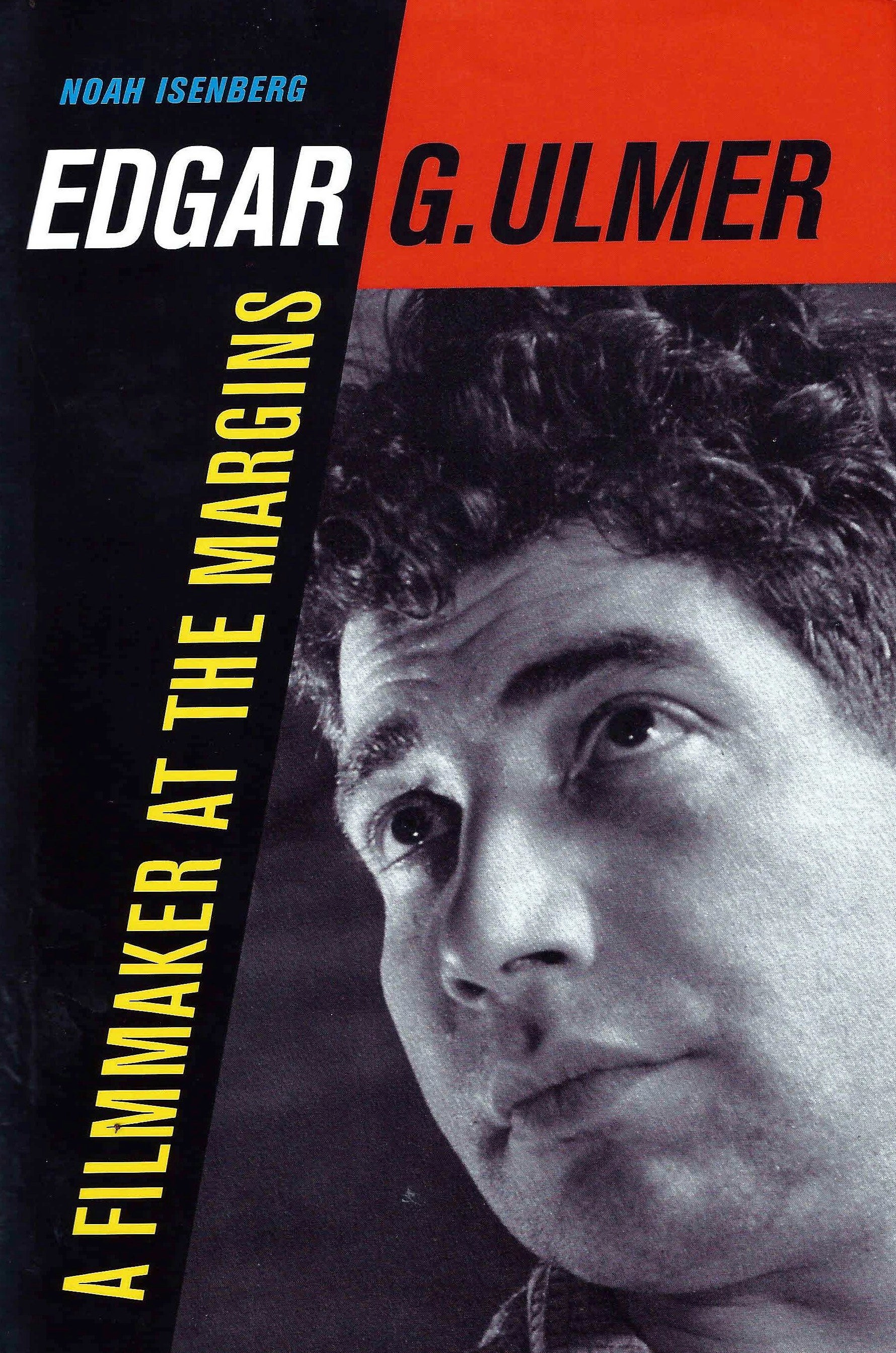

UCLA Film & Television Archive presented Her Sister’s Secret (1946), directed by Edgar G. Ulmer, at the TCM Classic Film Festival in Hollywood on April 12. Preserved by Scott MacQueen, Head of Preservation at the Archive, with generous funding from The Film Foundation, this film had been previously available only in poor quality 16mm prints. The film was restored from a surviving 35mm camera negative with the track re-recorded. It’s unprecedented visual quality for a PRC studio production is due to the fact that we had access to original elements and that the original work was produced with a substantially larger budget than standard PRC fare. Arianne Ulmer, the daughter of the director, was on-hand for our TCM screening and the event drew a sizable crowd. Ulmer is also the subject of a new book by Noah Isenberg, "Edgar G. Ulmer: A Filmmaker at the Margins" (University of California Press).

Her Sister’s Secret is a melodrama about two sisters, one of whom has a child out of wedlock, the other who is barren and adoption-willing—leading to a conflict that Bertolt Brecht would later rework in "The Caucasian Chalk Circle." I first wrote about Her Sister's Secret in an article on German exile cinema: “The film demonstrates an uncommon flair for the complicated nature of emotions, for the frivolity of love, the difficulties of motherhood, the barely concealed jealousy of the sister, while pitting itself against the unwritten Hollywood laws of a puritanical America, where a single mother has to be punished.” Indeed, unlike standard Hollywood melodramas there are neither villains nor evil characters, nor any moral condemnation—qualities that are common to German exile productions. As Brecht would expostulate in his "Refugee Dialogues," when you change countries as often as shoes, you develop a strong sense of moral relativity, because you have had friends that betrayed you, because surviving exile demands constantly shifting strategies and morally dubious behavior.

Arnold Pressburger, himself a refugee in Hollywood, bought the book by Austrian Hungarian novelist and screenwriter Gina Kaus, Die Geschwister Kleh(Berlin, 1932), and produced a French version of the film in Paris as Conflit (1938, Léonide Moguy). Pressburger then tried to remake the property in Hollywood, after producing Fritz Lang’s Hangmen Also Die! (1943), but he couldn’t get it past the Breen Office, which opined: "it is basically a story of illicit sex and illegitimacy, without sufficient compensating moral values,” meaning the heroine doesn’t die for her sins (Isenberg, p. 160). Pressburger therefore gave the property to a former film distributor from Berlin and, coincidentally, his brother-in-law, Henry Brasch, as a first Hollywood project. Financed at PRC, the producer brought in Edgar G. Ulmer, who hired Franz Planer as cameraman, another Austro-Bohemian-Jewish émigré like Presssburger, Kaus and Ulmer. Planer knew how to move a camera, German style, as the opening Mardi Gras scenes demonstrate. The music was supplied by another German émigré, Hans Sommer, so that all the principal talent behind the camera was from pre-Nazi Berlin. Meanwhile, you can see fellow Berlin compatriots, Felix Bressart, Fritz Feld and Rudolph Anders in crucial minor roles.

Arnold Pressburger, himself a refugee in Hollywood, bought the book by Austrian Hungarian novelist and screenwriter Gina Kaus, Die Geschwister Kleh(Berlin, 1932), and produced a French version of the film in Paris as Conflit (1938, Léonide Moguy). Pressburger then tried to remake the property in Hollywood, after producing Fritz Lang’s Hangmen Also Die! (1943), but he couldn’t get it past the Breen Office, which opined: "it is basically a story of illicit sex and illegitimacy, without sufficient compensating moral values,” meaning the heroine doesn’t die for her sins (Isenberg, p. 160). Pressburger therefore gave the property to a former film distributor from Berlin and, coincidentally, his brother-in-law, Henry Brasch, as a first Hollywood project. Financed at PRC, the producer brought in Edgar G. Ulmer, who hired Franz Planer as cameraman, another Austro-Bohemian-Jewish émigré like Presssburger, Kaus and Ulmer. Planer knew how to move a camera, German style, as the opening Mardi Gras scenes demonstrate. The music was supplied by another German émigré, Hans Sommer, so that all the principal talent behind the camera was from pre-Nazi Berlin. Meanwhile, you can see fellow Berlin compatriots, Felix Bressart, Fritz Feld and Rudolph Anders in crucial minor roles.

Some of the above I cribbed from Noah Isenberg’s new book, "Edgar G. Ulmer, A Filmmaker at the Margins," which I highly recommend. I actually once considered writing a biography of Ulmer myself, back in the late 1970s, because I was fascinated by this guy who was literally all over the map. Ulmer told Peter Bogdanovich in 1972 that he directed westerns at Universal, assisted F.W. Murnau on The Last Laugh, Fritz Lang on Metropolis and Cecil B. DeMille on King of Kings—all at the same time. Small wonder that Lotte Eisner called Ulmer the greatest liar in all of cinema. I realized quickly, though, that there weren’t enough archival resources available at that time to untangle the mess. Thankfully, Isenberg has taken on the task and solves many of the mysteries in the Ulmer biography. Isenberg constructs a plausible narrative for Ulmer’s origins in Bohemia, youth in Vienna, and entrance into Hollywood in 1923. He maintains a healthy skepticism as far as Ulmer’s claimed credits, but also shows great sympathy for his boundless energy in the face of sometimes staggering odds. Overall, Isenberg paints Ulmer as a kind of low-budget Ahasuerus, always adapting, yet also remaining true to a vision. One of the more shocking revelations of the book is how little Ulmer was paid for his work at PRC. When PRC loaned the director to Hunt Stromberg for the independent A-picture The Strange Woman (1946), starring Hedy Lamarr, Ulmer was paid $250 a week, but PRC received six times as much for the loan out, while the film eventually earned $2.5 million—without a penny more going to Ulmer (p. 164). Such was life at the bottom…

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation