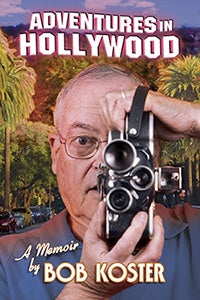

As mentioned in my last blog, I became friends with Bob Koster in the late 1990s, when I was working at Universal Studios. Bob is the son of Henry Koster, the well-known Hollywood film director. But Bob Koster also had a long career in the movies, working as an AD (Assistant Director) and UPM (Unit Production Manager). Now Bob has written an autobiography, Adventures in Hollywood: A Memoir by Bob Koster, which gives more information about the reality of Hollywood film production for what are called “below-the-line” staff positions than almost anything I’ve ever read.

Both jobs are Director’s Guild of America (DGA) approved positions, and require Guild membership, if the film production is a union shoot. An AD is responsible for making sure the production schedule is being kept, arranging logistics, preparing daily call sheets, checking cast and crew, maintaining order on the set, and taking care of the crew’s health and safety. The UPM will create a working budget during pre-production, is responsible for detailed planning and execution of the below-the-line costs for the production, negotiate deals for locations and equipment, and hires the technical crew. As Bob’s book demonstrates, the competence of individuals in both positions can make or break a production.

Bob Koster not only brought a wealth of experience to his job, he is also the author of the standard text for UPMs, The Budget Book for Film and Television (Focal Press, 2004), a revision of his earlier The On Production Budget Book (1997), and has been teaching film production at UCLA and various other universities for over a decade.

Adventures in Hollywood has 104 chapters, which I initially found perplexing until I realized that he dedicated a chapter to every film production he worked on in a career that started in the early 1960s. Some of those jobs lasted for almost a year, some for several weeks, some for only a few days, making me realize that everyone working in the craft end of film production is not only a freelancer, but constantly falling in and out of work, usually through no fault of their own. Like Bob, you can get fired no matter how excellent your work, because someone doesn’t like the look of your face or because they have a relative who needs a job.

The early chapters deal with Bob Koster’s childhood, which was apparently pretty lonely. His parents divorced when he as a small child, so Henry Koster, appears more as a phantom than a father, while his mother also kept up a busy schedule in her work as a literary agent. Bob was therefore relegated to entertaining himself, whether in his bedroom, or later at boarding school and at college. Probably not an untypical situation for kids of movie folk, and Bob certainly doesn’t complain about it, rather there is an under-current of melancholy in the early chapters. Having completed school at UCLA with honors, Bob joined the DGA West, then became a bank teller to learn accounting. Once he acquired those skills, he went back to the DGA to see about a job and was consistently met with, “Oh you’re Henry Koster’s kid.”

Not wanting to ride on his dad’s coattails, Bob decided to move to New York, where he eventually became a well-respected member of the production community. However, breaking in was not so easy, not only because there was a strong rivalry between production people on both coasts, but also because the DGA in New York considered themselves a separate union (at least for a while). Unlike Hollywood, New York production was mostly focused on commercials, television documentaries, and industrial films, with only occasional work in feature film production, when a Hollywood company decided to shoot “on location.” Bob worked them all, from J. Walter Thompson to CBS, eventually moving more and more into features after being hired as an AD on Valley of the Dolls (Mark Robson, 1967).

Bob relates mostly anecdotes surrounding the film productions he worked on, whether stories about hard-to-work-with actors or whacked out production assistants who hold up things; sometimes the crew works like a well-oiled machine. Most of the films -- even after he moved back to Hollywood in the early 1970s -- were not the great classics, but rather low-budget independent films or made-for-television films and series. He did work for the legendary Robert Downey Sr. on Greaser’s Palace (1972), Gordon Park’s The Supercops (1974), and Arthur Hiller’s The Man in the Glass Booth (1975), among many, many others. He also teases out the many differences between working in Los Angeles and working in New York, which should be of interest to anyone wishing to understand the nuts and bolts of the “industry.”

Bob relates mostly anecdotes surrounding the film productions he worked on, whether stories about hard-to-work-with actors or whacked out production assistants who hold up things; sometimes the crew works like a well-oiled machine. Most of the films -- even after he moved back to Hollywood in the early 1970s -- were not the great classics, but rather low-budget independent films or made-for-television films and series. He did work for the legendary Robert Downey Sr. on Greaser’s Palace (1972), Gordon Park’s The Supercops (1974), and Arthur Hiller’s The Man in the Glass Booth (1975), among many, many others. He also teases out the many differences between working in Los Angeles and working in New York, which should be of interest to anyone wishing to understand the nuts and bolts of the “industry.”

While the book could have used a copy editor to take out some of the occasional repetitions, this is a quick and enjoyable read, because Bob in person is a great reconteur and he writes the way he talks.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation