Film restoration and preservation are at the core of UCLA Film & Television Archive’s mission, and play an increasingly vital role in making cinema accessible to modern audiences, whether through public screenings, home video distribution or online delivery

The Archive’s “Out of the Past: Film Restoration Today” public film series––screening Monday nights this fall––offers audiences a behind-the-scenes look into contemporary restoration techniques and concerns, featuring newly restored prints and discussions with leading film preservationists from across the country.

Run in conjunction with a graduate seminar offered by UCLA’s Moving Image Archive Studies program, instructor Mike Pogorzelski, Director of Academy Film Archive, will be on-hand at the screenings to engage both students and the public.

There's No Business Like Show Business (1954)

On October 1, Vice President and Executive Director of Film Preservation at 20th Century Fox, Schawn Belston, joined us for the public premiere of a newly restored print of There’s No Business Like Show Business (1954), directed by Walter Lang. Digitally restored as part of the studio’s commemoration of the 50th anniversary of Marilyn Monroe’s death, both Monroe and the print dazzled attendees.

In the screening’s post-film discussion, Pogorzelski asked Belston to share some of the challenges he encountered during the restoration. While color fading emerged as one of the prominent issues, the problem was not so much being able to fix the color, but rather the ethics behind their color choices. With something as subjective as color in a film that Belston notes is “not modest in its palette,” the archivists decided to go back and try to best represent the original experience of audiences in 1954. Lacking a color reference, the team used other period Cinemascope materials shot on Eastman Color to help guide their decisions with the underlying goal to “let the film be what it was.”

In the screening’s post-film discussion, Pogorzelski asked Belston to share some of the challenges he encountered during the restoration. While color fading emerged as one of the prominent issues, the problem was not so much being able to fix the color, but rather the ethics behind their color choices. With something as subjective as color in a film that Belston notes is “not modest in its palette,” the archivists decided to go back and try to best represent the original experience of audiences in 1954. Lacking a color reference, the team used other period Cinemascope materials shot on Eastman Color to help guide their decisions with the underlying goal to “let the film be what it was.”

Belston also discussed a bit of the history of the 20th Century Fox preservation program. Fox was late to the game, starting their program around 1997/98 following the release of a new Star Wars home entertainment set and the shock of discovering that the film elements of such a highly valued property like the Star Wars Trilogy were not in as great of shape as they thought.

Pogorzelski and Belston also brought up the 2000 restoration of Robert Altman’s M*A*S*H (1970), a project they worked on together. Upon embarking on the restoration they discovered that both the original camera negative and original mono mix had been discarded, deemed too deteriorated by predecessors. But even with the loss of such crucial original elements, the story has a happy ending. Altman was actually very pleased with the final results of the restoration, with Belston claiming Altman felt the original look of the film “never looked quite bad enough for him.” While in this case the filmmaker’s original intent was in a way restored, this remains a powerful example of just how at risk film materials can be.

Laurel & Hardy Restoration Project

The Archive’s own Head of Preservation, Scott MacQueen, screened a pair of Laurel & Hardy shorts and presented his findings on our Laurel & Hardy/Hal Roach Collection on October 8. Macqueen recently completed a full inventory of the collection as part of our preservation effort to restore all surviving Laurel & Hardy negatives and his results were staggering.

MacQueen detailed the history of the Laurel & Hardy films and their “devolution of quality” that largely started with Hal Roach’s sale of the library to other distributors. But even before the sale, Roach did not hold the sanctity of the original film materials in very high regard. In order to avoid paying taxes, he would take a truck full of film and drive it across state lines to Nevada where for a few weeks the film would bake in the desert heat, accelerating decomposition.

While Hal Roach Studios would be bankrupt by 1959, Laurel & Hardy were still enormously popular across the globe and the films were constantly being reissued. But these new distributors, as MacQueen said, “didn’t want to spend a dime” on taking care of the film materials, and their condition suffered drastically. In fact, original nitrate materials were nearly discarded were it not for former UCLA colleague Rob Stone's intervention and the film has since remained in our vaults.

As mentioned previously, MacQueen has since run a full inventory and he spoke of just how “important documenting inspections” is to the preservation process. MacQueen was able to document issues of film turning to powder and even found that 20% of the collection was misidentified, leading to the discovery of the original camera negative for reel 1 and 2 of The Music Box (1932).

Using side-by-side image comparisons, MacQueen showed the audience just what bad shape many of the materials were in, including damaging splices that MacQueen described as equivalent to being “limb by limb hacked off and replaced.”

But even amidst the veritable horror stories MacQueen shared, he felt confident that with the technology and expertise of the Archive, Laurel & Hardy will shine brightly once again. To illustrate, the program closed with a screening of the Archive’s restoration (led by UCLA preservationist Jere Guldin) of the 1933 original release of Busy Bodies that lacked many of the distracting imperfections that marred the original nitrate print screened earlier in the evening.

No Man of Her Own (1932)

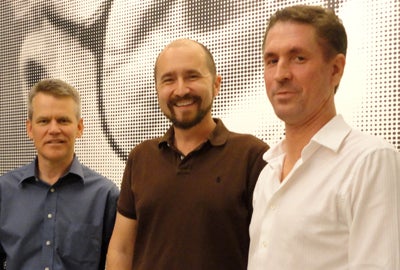

October 15 brought Bob O’Neil and Mike Feinberg of Universal Studios to the Billy Wilder Theater to discuss their work on the Carole Lombard and Clark Gable Pre-Code romantic drama, No Man of Her Own (1932), directed by Wesley Ruggles. While introducing the film, O’Neil emphasized the collaborative nature of film restoration and thanked the labs, personnel and archives that contributed to the success of this particular restoration.

O'Neil also noted that even with more than 3 million holdings in their own vaults, Universal will sometimes need to turn elsewhere for critical preservation elements. In the case of No Man of Her Own, Feinberg and O’Neil discovered Universal had only a 3rd generation duplicate negative. Fortunately, UCLA Film & Television Archive had a 35mm nitrate print, which after extensive testing of several different elements proved to be the best source material. Even so, that print required more than 28 minutes of replacement footage, and Feinberg eloquently described the painstaking process of piecing together existing materials in order to achieve the most complete and highest-quality restoration.

O'Neil also noted that even with more than 3 million holdings in their own vaults, Universal will sometimes need to turn elsewhere for critical preservation elements. In the case of No Man of Her Own, Feinberg and O’Neil discovered Universal had only a 3rd generation duplicate negative. Fortunately, UCLA Film & Television Archive had a 35mm nitrate print, which after extensive testing of several different elements proved to be the best source material. Even so, that print required more than 28 minutes of replacement footage, and Feinberg eloquently described the painstaking process of piecing together existing materials in order to achieve the most complete and highest-quality restoration.

While addressing the MIAS students in attendance that evening, O’Neil praised the collegiality and mutual cooperation of the film preservation field––and while professing to be an “analog guy until I die”––admitted that he was “envious” of the potential of the digital future. O'Neill remarked that “since we have saved [films] for the future generations,” the students will have the “opportunity to do something pretty special” with the resources of digital technology in terms of both access and preservation.

Before the screening, Feinberg pointed out that Universal selected No Man of Her Own for restoration in part because of the on-screen chemistry of future and fabled spouses Gable and Lombard. Indeed, this film is the only time the pair appeared on the big screen together and the audience that night was the appreciative beneficiary of this unearthed footnote in film history.

And thanks to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Foundation for its generous support of this series.

For more information and a complete schedule of these FREE screenings, visit “Out of the Past.”

For additional images from the program, please visit our galleries.

For more information about UCLA’s program in Moving Image Archive Studies, visit the Archive website.

To learn more about our Laurel & Hardy Restoration Project and how you can help, please visit here.

—Meg Weichman, UCLA Film & Television Archive.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation