LGBT film festivals are a lot of fun, and they were particularly fun in the late-1990s, when I was programming for Outfest. I’ve been reflecting on those days now, as we present UCLA Film & Television Archive’s ongoing series "NQC @ 20: Revisiting New Queer Cinema" (continuing this Sunday, March 25, with Gregg Araki's The Living End: Remixed and Remastered (1992) featuring Araki, and actors Mike Dytri and Craig Gilmore in person).

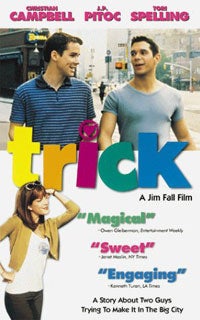

Outfest, which was 15 years old when I began working there, was in the early stages of a concerted push to coordinate its cultural efforts with its geographic setting, incorporating the talents and strengths of Hollywood media companies on its board of directors and sponsors, and facilitating industry “access” for visiting filmmakers. A flurry of fun and well-crafted feature films—including Brian Sloan’s I Think I Do, Tommy O’Haver’s Billy's Hollywood Screen Kiss, Jim Fall’s Trick and Greg Berlanti’s Broken Hearts Club—celebrated the ascendant lifestyles of an urban and industrious gay public: out, stylish, healthily libidinous, upper middle-class.

The happiness seemed somehow tied to other developments in society: the American economy was perceived to be quickly expanding, largely as a result of the “dot.com boom,” a bubble that was set to burst. But for a few moments, the internet seemed to offer queer communities a new and dynamic connectivity, and endless entrepreneurial possibilities. I was approached by many impresarios seeking my help in creating websites to showcase “gay shorts” (or “product,” in the vernacular), and for a little while, Atom Films seemed like the gay filmmaker’s fast track to success. Somewhat more profoundly, the AIDS epidemic was seeing rapid changes in available therapies, with the introduction of sophisticated drug “cocktails” that were bringing countless queers almost literally back to life in the West, even as the disease roared its way through the Third World. “AIDS is over” was a frequent overstatement on the street, and an unstated part of the community’s mood at the time.

One also noticed, in gay social settings (such as the unique, attractive, charged spaces that queer festivals provided), a heightened presence of high-level sponsors courting a publicly-touted new “Gay Dollar,” and offering accoutrements of a complete gay lifestyle: cruises, air travel, travel guides, high-end fashion, luxury automobiles and specialty cocktails. By the mid-1990s, Outfest had garnered more sponsors, and more sponsor money, than had probably been dreamt of in its first decade. These had helped to vault the festival very rapidly from an interesting local affair to a high-impact, “full-on happening” (as it was called in the Los Angeles Times) with an international reach, attracting more filmmaker attention and higher profile films, more industry involvement, more audiences (to well-stocked parties as well as premieres), and an expanding and diverse sponsor base.

There was also a lot of dialogue about the expansion of gay visibility in the mainstream, and indeed, the film industry itself seemed to budge a little bit in creating a space for leading gay movies. Notably, Trick was given a remarkable public relations push in the Los Angeles market following its 1999 premiere at Outfest with billboards and bus benches promising “It’s Big. It’s Beautiful. And You’re Gonna Love It.”

It was a heady time to find myself at the center of the action, and with my colleagues and friends, I had a lot of fun in this clamorous, glamorous environment. I was thrilled to think that we were at the center of developments that would have importance to gay people all over the world. This thought still brings a thrill.

Still, from nearly the very start of my tenure as a programmer, I felt a certain uneasiness about the total picture of the mid-1990s, though it took me a few years to give words to it. Somehow, it felt like living on a sugar high. My first few years of exposure to Outfest were spent as a volunteer, peeking into various features after the credits had run. Despite the penchant for celebration that pervades most queer culture (and most film festivals), a whiff of siege mentality could still be sensed. One was viewing rare film artifacts in a specialized and more or less isolated queer community setting.

I often thought back to my own, then-recent, closeted days, when I had first heard of Outfest (then the “Los Angeles Gay and Lesbian Film and Video Festival, presented by the Gay and Lesbian Media Coalition.”) The thought of mingling at a social event, rehearsing publicly the same self-defeating dialogues I had rehearsed privately for years, was none-too-savory, giving the lie to many mid-'90s features in which the cute young thing arrives in West Hollywood’s gay ghetto, instantly enchanted by the summery sight of scantily-clad and well-built fellow queers. Upon reading about Todd Haynes’ historic Poison, I had initially reacted with an instant feeling of dread to descriptions of its images of humiliation, disfigurement and paranoia employed as metaphors of AIDS and various gay complexes.

"To me, any queer cinema was new. But Rich’s case that these were in fact the best indie films at the time was one that I found hard to resist. Each of them opened a new space in my consciousness, in which I found another portion of myself waiting for the light to flood in."

I finally saw Poison on video (more private that way, anyhow), and viewed in their theatrical releases both Tom Kalin’s captivating, unlikely masterpiece Swoon (featuring two sympathetic and sexy lovers who commit a heinous crime but maintain audience sympathy) and Gregg Araki’s balls-out road movie The Living End (rudely shoving AIDS out front and center as a topic) before I came to know that these films and others had been theoretically grouped by critic B. Ruby Rich into an intellectual category dubbed “New Queer Cinema.” To me, any queer cinema was new. But Rich’s case that these were in fact the best indie films at the time was one that I found hard to resist. Each of them opened a new space in my consciousness, in which I found another portion of myself waiting for the light to flood in. It was remarkable that for a buttoned-down personality like my own, so many pictures about outsiders dealing with AIDS, political repression, self-loathing and other complicated states offered metaphorical answers to deeply personal, unstated crises.

So to later be an agent in the unfolding of a differently understood queer cinema was a strange thing. Notwithstanding some high points of aesthetic and political fusion (Patrik-Ian Polk’s Punks, with the first black male kiss in a mainstream feature, and John Cameron Mitchell’s transgender fantasy Hedwig and the Angry Inch), the culture was seemingly taking a boomerang’s turn into a different direction; one that can be understood as setting up such later cultural products as TV’s “Will And Grace,” Bravo’s “Queer Eye for the Straight Guy,” queer cable channels themselves, and an American queer independent film landscape currently pointed in no particular direction that I can discern.

Queer mass media has also been a rudder through the choppy waters of progressive battles over gay marriage and parenting, and the fate of gays in the military—important contests, strangely less drastic in feeling than the 1990s struggles led by radical groups Act Up and Queer Nation, respectively, over access to AIDS medications and against anti-gay violence on the streets. If the seeming promise of an expanded queer media complex has led to lifestyle-oriented programming which at any rate promises pleasure and eschews discomfort, that may be a thing to celebrate as indeed, a new arrival. But no arrival is final, and one may ask which media products serve queers who feel more “queer” than “gay.” Even with the trappings of a comfortable modern life and with expanded media options, my queer eye somehow doesn’t often recognize the queer me on TV, nor often see on movie screens a cinema that this community would seem to deserve.

Working in identity-based media such as queer film, one is usually fixated upon the present, as each year’s films offer the possibility of new gains in consciousness or political achievement. Hindsight, of course, is 20/20, and it’s a luxury of repertory cinema programming to look over one’s shoulder, historically, while barreling forward into film history. It’s hard to judge from the present moment what will have staying power, or haunt audiences and generations of the future. But by now I’ve seen a lot come and go, and the New Queer Cinema still has a hold on me.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation

Comments