There were a lot of interesting and rare films at this year’s Cinecon 55 at the Egyptian Theatre, Labor Day weekend in Hollywood. However, the film I was most keen on seeing was The Glass Wall (1953). It is the story of a Displaced Person, a survivor of Auschwitz and apparently a Communist prison in Hungary, who stows away on a ship to New York. He is told by American immigration officials (INS) that he can’t enter the United States and will be deported the next day, unless he can actually prove he’s a bone fide DP. He jumps ship and the chase begins. Co-written and produced by Ivan Tors, née Iván Törzs, a pre-World War II refugee from Hungary, this film noir is one of the few American films to directly address the refugee crisis before and after World War II. UCLA Film & Television Archive recently restored Voice in the Wind (1944) and I’ve written about So Ends Our Night (1941), two other American melodramas about refugees from Nazi Germany. Then there is Casablanca (1942), maybe the most famous refugee film of all.

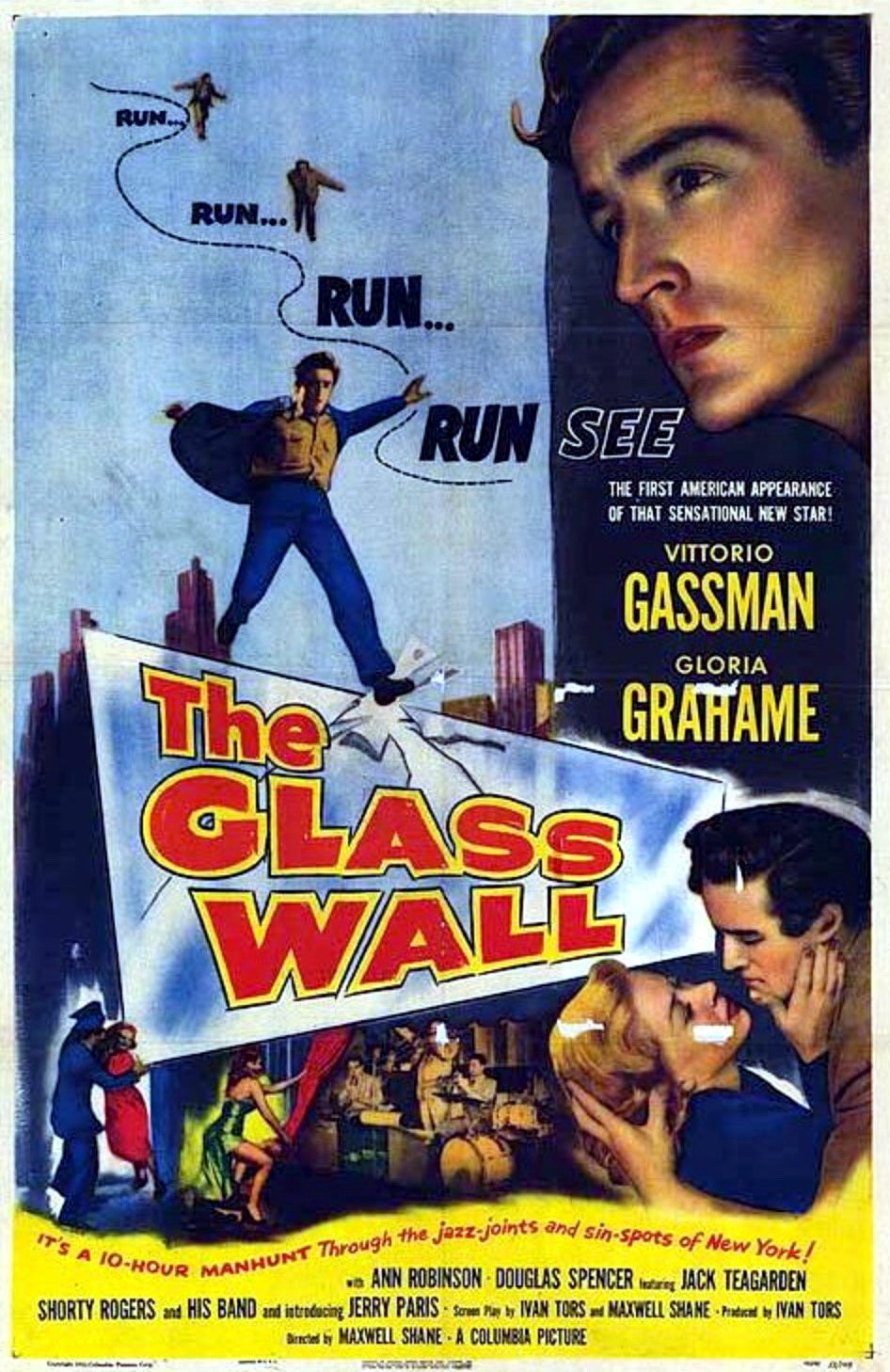

The Glass Wall stars the Italian actor Vittorio Gassman as Peter Kaban, a young Hungarian refugee who spends much of the narrative trying to find an American soldier whose life he had saved when both were on the run in Nazi-occupied Europe, who could prove he is what he says he is. Peter remembers that Tom was a musician in Times Square, so much of the film takes place on location at night in and around Times Square. Brian Camp has written an excellent blog about all the Times Square theaters and marquees seen in the film, but my focus is more on the film’s attitudes towards immigration. In the course of his search of New York’s clubs and bars, Kaban meets a down and out young woman named Maggie (Gloria Grahame), and a stripper (Robin Raymond) and her Hungarian family, both of whom sympathize with his flight from the authorities. Meanwhile, Tom, who is a clarinetist, sees Peter’s picture in the paper and eventually contacts the INS to verify Peter’s story. The film climaxes at dawn atop the United Nations building in New York, where Maggie, Tom and an INS official have chased him. Moments before, Peter makes an impassioned plea in the empty chambers of the U.N. Human Rights Commission. This was the first and only Hollywood film given permission to shoot inside the United Nations until 2005.

The chase narrative of The Glass Wall closely resembles that of numerous Hollywood anti-Nazi films made during World War II, like The Seventh Cross. In that film, Spencer Tracy plays an escapee from a Nazi concentration camp who is helped in his flight by anti-Nazi Germans, thus setting up a dichotomy between ordinary, democratically-minded citizens and the Fascist government. Ivan Tors has a trickier job, because while the INS is initially seen as a menace to freedom loving people, The Glass Wall couldn’t appear to be anti-government film, given this was the blacklist era. Tors solves the problem by having the INS official change his mind about Kaban, once he hears Tom’s story, but Kaban doesn’t learn that until the film’s climax, so he keeps running. The American government’s ambiguous role here was however richly deserved.

The Displaced Persons Acts of 1948 and 1950, passed by the U.S. Congress, allowed individuals to enter America who were victims of persecution by the Nazi government or who fled persecution and could not go back to their native country for fear of persecution, based on race, religion or political beliefs. Congress approved the legislation because hundreds of thousands of victims of Nazi terror had been stranded in Germany and Austria at the end of World War II, but the government had not always been so sympathetic. Before WWII, a strict quota system had been in place, which severely limited the immigration of Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi persecution. As David S. Wyman details in his book, Paper Walls: America and the Refugee Crisis, 1938-1941 (1985), anti-Semitic officials in the State Department guaranteed that even those limited quotas were never filled, thus sending untold numbers to their death in the camps. But the Displaced Persons Act specifically barred anti-Communist refugees from Eastern Europe, except Czechoslovakia, from entering the United States. Five months after The Glass Wall premiered in March 1953, Congress passed the Refugee Relief Act of 1953, which allowed for 45,000 Eastern Europeans to enter the U.S., while the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 forced Congress to accept another 30,000 Hungarians in the country.

Born in Budapest in 1916, Iván Törzs and his brother had entered the United States in July 1939, presumably on student visas, just days before World War II began. Tors had written a couple of plays before emigrating, but it wasn’t until after serving in O.S.S. during the war that Tors became a scriptwriter at MGM. He would become famous in Hollywood for both sci-fi films (The Magnetic Monster, Gog) and underwater animal films (Sea Hunt, Flipper), but this would be his one foray into overt political content that acknowledged his own status as a refugee. Given today’s politics of immigration, Cinecon could not have been more timely with their choice.

< Back to the Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation

Comments