On the eve of August 22nd, the 45th edition of The Reel Thing opened at the Linwood Dunn Theatre of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences with a reception and special program of Serge Bromberg’s “Retour de Flamme – Cinema Firsts.” The next morning, the two-day symposium began, offering its usual mix of technical papers on film restoration and other film historical projects. Focusing on new film restorations, here are some of the highlights:

Lars Karlsson from the Swedish Film Institute described the efforts of the past several years to restore the work of Ingmar Bergman, and thus complete the preservation work begun decades ago by Bergman’s producer, Svensk Filmindustri. Lars began by noting that Bergman was a huge supporter of film preservation, having himself created the largest private film collection in Sweden with his own cinema in a barn, where he regularly screened classic films. Before his death in 2007, Bergman also pushed the government into significantly increasing funding for the Swedish Film Institute, which now amounts to $1.5 million per year for preservation alone. Since 2016, the Institute has been producing new digital masters from Bergman’s original camera negatives, which had been used repeatedly to make new 35mm prints, but were still in surprisingly good condition. Karlsson then showed a clip from the new restoration of The Seventh Seal (1957), which looked amazing.

The Seventh Seal (1957)

In the afternoon, James Mockoski and Colin Guthrie, film archivists for American Zoetrope, and Vincent Pirozzi from Roundabout, a post-production lab, discussed new work done on Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979). Noting that United Artists had originally released the film in 1979 in 70mm, six-track “Quintaphonic Sound,” Mockoski stated that Coppola had not been happy with the 147 minute release version, completed under pressure after the film’s troubled three-year production history. In 2001, the director decided to add 45 minutes to Apocalypse Now Redux, but then realized that film was too long. For the new digital restoration, which had its premiere in August 2019, the film was shortened to 183 minutes, still making it significantly longer than the first release. Happily the original negatives were still in great shape, as was the color in two surviving 70mmprints from 1986, so the restorationists had plenty to work with. More difficult was the sound restoration, which began with the original magnetic sound tracks, but needed much work to remain faithful to the films complex sound design. The film has now opened in limited theatrical release and is also available on Blu-ray.

Saturday morning began with a presentation by Dennis Doros, co-owner of Milestone Films, one of the country’s leading distributors of classic and forgotten films, who introduced Filibus (1915). Not exactly a lost film, this Italian crime drama starred a beautiful jewel thief/aviatrix with feminist overtones and was often double-billed with the French Fantomas (1915), because it was thought to be a serial, when in fact it was released as a single feature. A nitrate print had survived in the Desmet Collection at the Eye Film Institute in However, as Doros explained, the lead actress had been misidentified as the Italian diva Cristina Ruspoli, who plays Filibus’ sister. After much research, it was determined that the star was Valeria Creti). And while some contemporaneous critics criticized the cheap special effects, the clip Doros screened from the new Blu-ray looked like fun.

Saturday morning began with a presentation by Dennis Doros, co-owner of Milestone Films, one of the country’s leading distributors of classic and forgotten films, who introduced Filibus (1915). Not exactly a lost film, this Italian crime drama starred a beautiful jewel thief/aviatrix with feminist overtones and was often double-billed with the French Fantomas (1915), because it was thought to be a serial, when in fact it was released as a single feature. A nitrate print had survived in the Desmet Collection at the Eye Film Institute in However, as Doros explained, the lead actress had been misidentified as the Italian diva Cristina Ruspoli, who plays Filibus’ sister. After much research, it was determined that the star was Valeria Creti). And while some contemporaneous critics criticized the cheap special effects, the clip Doros screened from the new Blu-ray looked like fun.

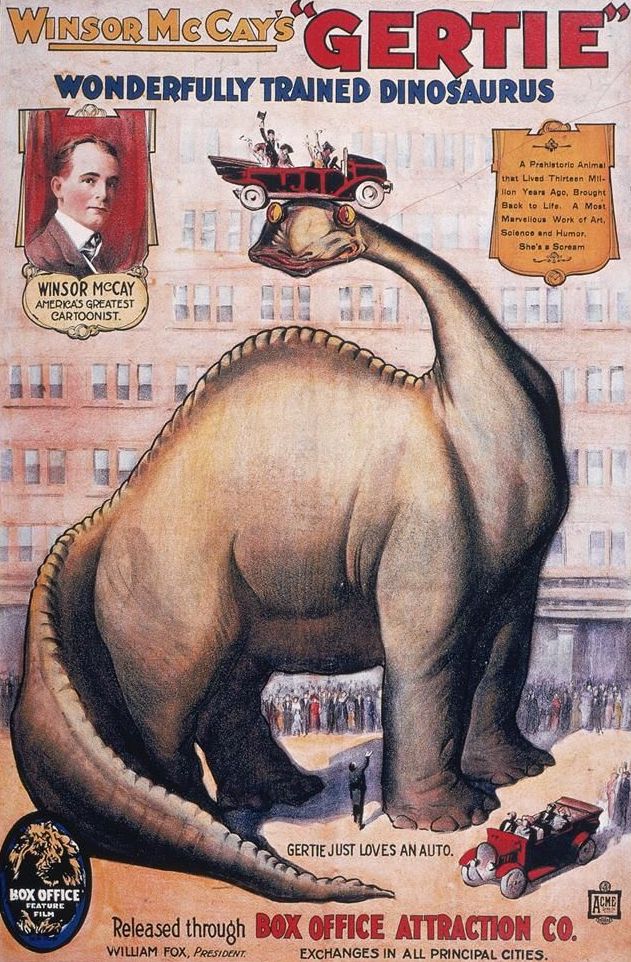

Saturday morning saw a live performance of Winsor McCay’s Gertie the Dinosaur (1914), as it was originally performed by McCay in vaudeville. Introduced by animation historian Donald Crafton, with Gabriel Krut as Winsor McCay, and accompanied on the piano by Michael Mortilla, participants got to see the original live version, before Samuel Goldwyn bought the rights and distributed a self-contained film version in December 1914. As Crafton noted, McCay, a well-known cartoonist for New York newspapers had initially created an “interactive” version for the stage, where he performed live onstage as a dompteur, coaxing Gertie out of her cave on screen and getting her to do tricks. Since the original stage version has not survived on film, it was recreated through painstaking research, incorporating nitrate footage from the Cinémathèque québécoise with original drawings from the Winsor McCay estate, all of it digitized in 2K. The Gertie Project then produced a script for the actor and a new score, making this event the delight of the conference.

Unfortunately, prior appointments hindered me from attending Rita Belda’s presentation of Sony’s new digital restoration of George Cukor’s Holiday (1938), as well as evening screenings of The Devil Thumbs a Ride (1947) and Walkabout (1971). But The Reel Thingis always worth the price of admission.

< Back to the Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation