Tonka of the Gallows

There seemed to be general agreement that the true discovery of the recent San Francisco Silent Film Festival was Karel Anton’s 1930 Czech film, Tonka Šibenice / Tonka of the Gallows, starring Ita Rina, the great Vera Baranovskaya (of Pudovkin’s Mother fame), and Jack Mylong-Münz. Originally released as an sound film with a song and a musical track, the film stylistically is a late silent film with a spare use of intertitles. First shown at MoMA two years ago, Tonka was introduced in San Francisco by Eddie Muller, who focused on its darkness and pain, but despite its tragic story, I saw it communicating the power of humanity.

The film opens idyllically with a young woman, Tonka, riding a small gauge train to her village in the countryside on a beautiful spring day (the four seasons will define Tonka’s fate). After seeing her mother and her ex-boyfriend who still wants to marry her, she returns to Prague and the brothel where she works. We think we are in a stereotypical movie about a country girl gone to seed, but then two cops turn up to ask for a volunteer to spend a last night with a man condemned to death. Tonka volunteers and spends a night comforting (without sex) the doomed man, who seems brutish as first, but becomes a child in her arms. For her extraordinary act of human kindness, which we experience with great sympathy, she is punished. First she is ostracized by her female colleagues, then driven away by her village and her fiancée on her wedding day for being a “gallows widow,” ultimately dying an acute alcoholic. In an extraordinary dream sequence before she dies, we see the life that might have been.

Ita Rina, a radiant actress who had previously played a station master’s daughter seduced by a travelling slick salesman in Gustav Machaty’s Erotikon (1929), gives an amazingly vulnerable, fragile and deeply caring performance. She moves from light to darkness to a moment of happiness and to the depths of despair without a touch of sentimentality or false emotion. What American reviewers missed was that Tonka’s story is based on a real life. The script by journalist Willy Haas adapts a newspaper story by Egon Erwin Kisch, the so-called “rasende Reporter” (raging reporter) of 1920s Berlin by way of a stage play by Emil Artur Longen.

Born in 1885 into a German speaking Jewish family in Prague, Kisch began working as a journalist in 1906 at the German language Prague Tagblatt, after publishing a book of short stories with financial help from his mother. He belonged to a circle of writers in Prague that included Franz Kafka, Max Brod, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Jaroslav Hašek, the author of The Good Soldier Svejk. In 1911 he interviewed Thomas Alva Edison, but it was his investigation in 1913 of Col. Alfred Redl’s suicide that broke the biggest Austro-Hungarian espionage affair before World War I. The same year Kisch moved to Berlin to work for the Berliner Tagblatt. Badly wounded in 1916 on the Russian front, Kisch was radicalized and eventually joined the Communist Party. Kisch’s journalistic style set new standards, openly partisan and focusing on ordinary citizens, but sometimes also included embellishments to the truth. Nevertheless, he became a household name. After Hitler’s election, Kisch went into exile, eventually spending the war years in Mexico City, before dying in Czechoslovakia in 1948.

In 1921, he published his story about the fate of Tonka Šibenice, having interviewed her in her squalid quarters on Kožná Street in Prague’s old town 10 years earlier; Kisch and Kafka grew up a few blocks from there in the Jewish quarter. A prostitute working the street for more almost 30 years whose real name was Antonie Havlova, Tonka apparently died in hospital a few weeks after the interview. Even though she worked in a fancy brothel when on August 12, 1881, she volunteered to spend a night with a serial killer of three young women. Ferdinand Prokůpek was scheduled to be executed the next morning. Originally, another “retired” working woman, Mrs. Olga Petříčková was supposed to service the convict, but was rejected by him, despite the fact that he was himself apparently physically repulsive. After her night with the convict, Havlová was thrown out of her job, because customers avoided her for fear of being “infected” by the gallows, and she thereafter only plied her trade on the pavement. However, an amateur Czech historian, V. Bavor, has been unable to find official records of the deaths of either Tonka or Prokůpek, so Kisch’s article remains the only source for the story.

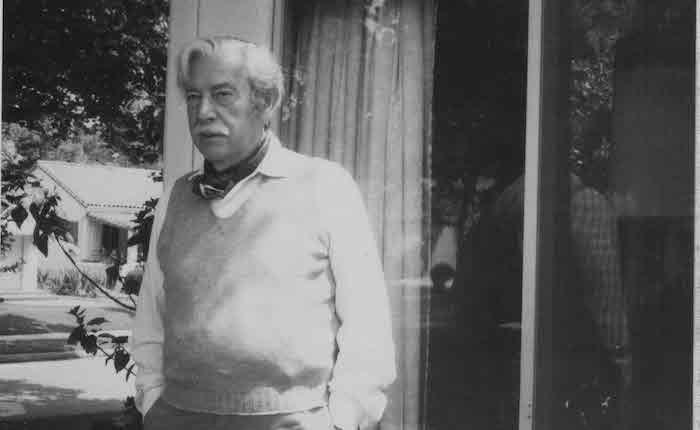

John Mylong

Postscript: Loved seeing John Mylong in a starring role. Like many Jewish actors, he fled Nazism after playing supporting roles in almost 100 films in Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia, then became a bit player in Hollywood where he often played Nazis. I interviewed him three months before he died in September 1975, having just married again at 82, and being surprisingly happy with his life.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation