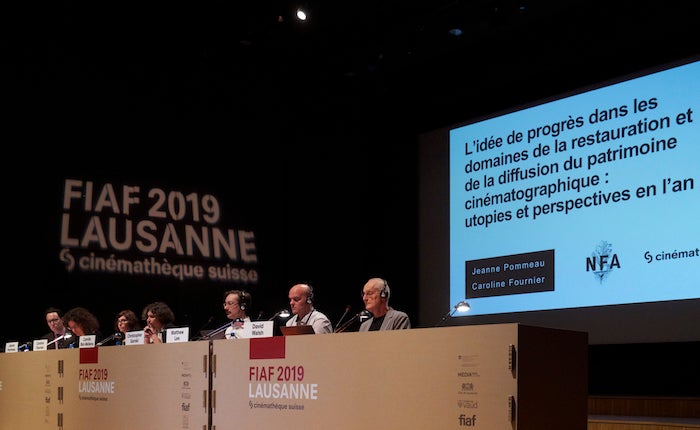

One of the most interesting sessions of the recent International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF) Symposium in Lausanne focused on film restoration ethics and practices. The event began with Jeanne Pommeau, a preservationist at the Czech National Film Archive in Prague, and Caroline Fournier, head of the Film Department at the Cinémathèque Suisse in Lausanne. In their paper on “the idea of progress in the restoration and dissemination of film heritage,” both addressed the incredible impact digital technologies have had on film preservation. It ended with a report by Matthew Lee and David Walsh, the head and former head, respectively, of the Imperial War Museum’s Film Department, about the experience of working with director Peter Jackson on They Shall Not Grow Old (2018).

Pommeau opened the session with the notion that “an ideology of perfection has gripped the field” with the arrival of digital technologies. Whereas analog restoration could only improve the quality of degraded and damaged images, new digital tools allow film restorers to reveal details that were previously unseen by the naked eye in projection. Through dirt removal, digital repairs and extreme sharpening tools, the image is made more “perfect” than it could have ever been in the analog world. Furthermore, stabilization tools allow for a rock-steady image, impossible in analog projection, given the collision of machine sprockets and film sprocket holes. Such improvements inhibit any attempt to reproduce the experience of the original work, as it was seen at the time of release. Pommeau recommended removing some of the ravages of time, but not over-restoring a work, although she admitted that many argue that the original filmmaker would have used all the tools available, were they at their disposal. It is the market that now demands the best possible copy, regardless of its original state. Quoting Cesare Brandi’s Theory of Restoration, Pommeau in closing argued that the restorer should be mindful of the work’s patina and that any intervention should be reversible, hardly a criteria for many commercial restorations today.

Photos by Mikko Kuuti

Caroline Fournier continued this line of thought in her presentation, noting that an “ideology of resolution” is dominating the field. Younger viewers, unfamiliar with 35mm film projection and consuming movies on their smart phones, will no longer accept scratches and other imperfections in the image. Fournier, however, points to the commercial companies that are creating the demand for films that are perfect, fulfilling the vendor’s dream of film immortality by abolishing the element of time. And while it is a utopia to recreate the original experience of a film, the new digital technologies actually frustrate that effort. Restoring and screening historical films should be a matter of compromise, while maintaining a strict code of ethics. Maybe, Fournier suggests, two versions should be produced: an archival version that doesn’t look like it was produced for Netflix in 2019, intended for long-term preservation, and a “popular” version for the marketplace and contemporary screenings.

The presentation really struck a chord with me, because I have been long concerned about the tendency of commercial digital technicians to over-restore films. As early as November 1991 at a film restoration symposium (ironically) in Lausanne, I expressed concern about the historical veracity of film restorations, especially in terms of new sound technologies. That was before the advent of today’s digital restoration tools. I have repeatedly heard from colleagues in the studios that their restorations only do what the filmmaker would have tried, if they had the tools available, but such efforts take a work out of history and into an ahistorical no-man’s land. The degree to which that actually happens became very clear in the Imperial War Museum’s final presentation of the session.

After going into the genesis of They Shall Not Grow Old, a celebration of the end of World War I (discussed in a previous blog), restoration producer David Walsh detailed the many ways Peter Jackson manipulated the materials that were previously digitized and restored by the Imperial War Museum. Many of these changes—including 3-D, colorization grain reduction, sharpening of the image, cropping the image, and conforming the film to sound speed—are a matter of public record and have been commented on favorably by the press and audience. More troubling, given that Jackson is insisting on calling his film a restored documentary, is the outright falsification of images. Deciding what colors to paint the sky and the faces and uniforms of soldiers is one thing, but more was done. Whole parts of images were removed and then repainted, e.g. in one scene, houses were removed and replaced with green trees to make the composition more pleasing. The film’s many explosions were also enlarged and repainted in order to make them bigger and more Hollywood-like, especially when combined with the Dolby stereo sound added to the track to heighten the visual impact. Indeed, according to Walsh, virtually every scene includes some redesigning of the actual image. This is certainly acceptable, if making a work of art that does not claim to be a restoration. But one wonders, what is to stop anyone from turning The Big Parade (1925) into a new sound and color spectacle and claiming it to be a restoration? It is also troublesome that Jackson has chosen to show only images of white British soldiers, even though tens of thousands of soldiers of color from Jamaica to Hong Kong, India to Kenya, fought beside Britons as members of the British Empire.

< Back to the Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation