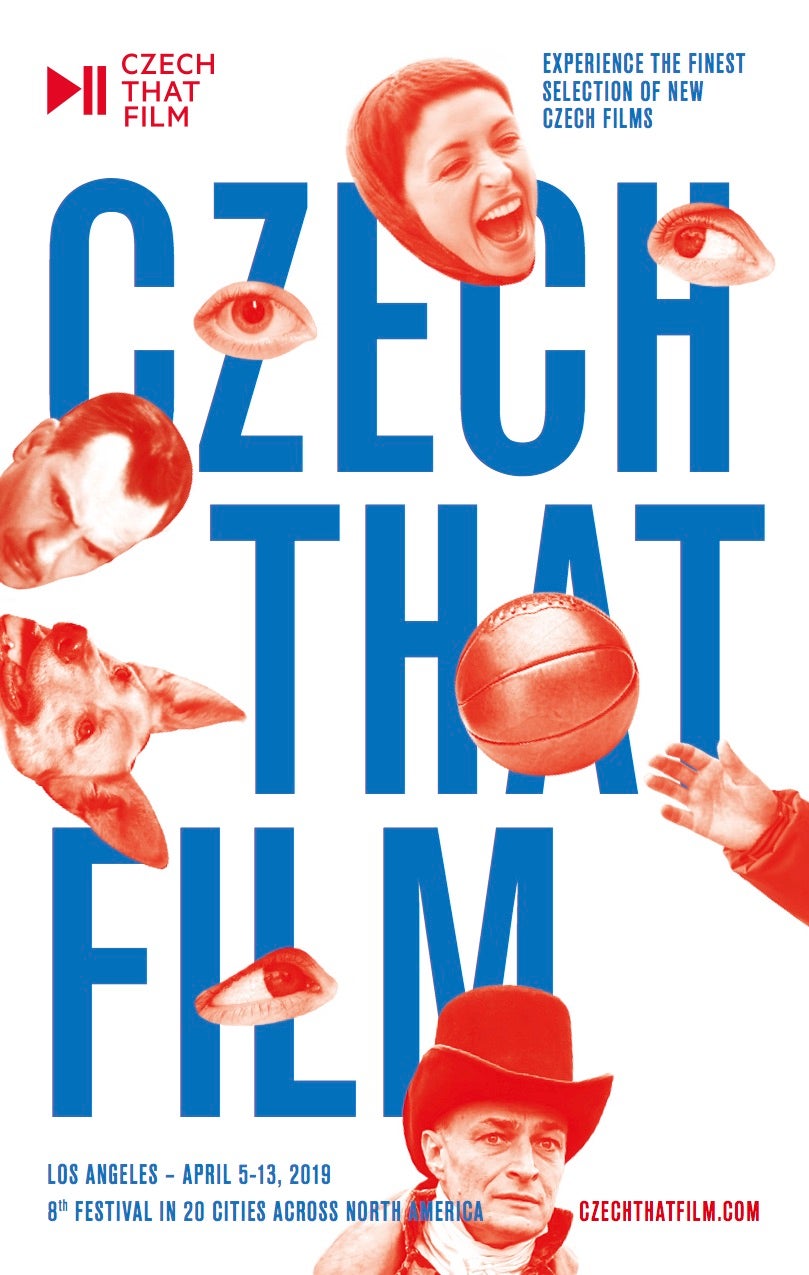

On April 5th, UCLA Film & Television Archive opened the 8th edition of Czech That Film at the Billy Wilder Theater with the U.S. premiere of Golden Sting (Zlatý podraz, 2018), a Czech film directed by Radim Špaček. The film festival, which will travel to 23 cities across the U.S. and Canada, was curated by Michal Sedlaček, the former Consul General of the Czech Republic in Los Angeles and now head of the Office of Czech American Relations in Prague, and co-organized by the present Czech Consul in L.A. and his team. While last year’s series coincided with the 100th anniversary of the founding of Czechoslovakia's democratic republic, which fell 30 years later in a Communist putsch, this year's series coincides with the nation's democratic rebirth in 1989.

For the booklet accompanying the series in L.A., I wrote the following:

“30 years ago, the Velvet Revolution brought an end to more than 40 years of Communist dictatorship and reinstated a democratic tradition that had made the Czech Republic one of the most advanced democracies in Central Europe between 1918 and 1948. For me personally, it also meant that my dad could return to his home town of Prague after being in exile for just as many years. I’m therefore extremely happy that UCLA Film & Television Archive will help celebrate these events with Czech That Film, a film series that UCLA has participated in, almost since its inception.

One of the signature films at the festival is a biopic about Jan Palach (2018) who martyred himself through self-immolation in 1968 in Wenceslaus Square in Prague to protest the invasion of Soviet Russian troops on August 21st, which ended the country’s first attempt to reestablish democracy. Visiting my grandparents for several weeks and only leaving days before the invasion, I remember those heady days, listening late at night to students, workers, and leading politicians discuss the country’s fate in the Old Town Square. Three years later, I was back in Prague, now a young film student, following up on what had happened to the Czech New Wave, which included Oscar winners Miloš Forman, Ivan Passer, as well as Vera Chytlová, Jiři Menzel, Jan Nĕmec, Juraj Herz, and Karel Kachyna, whose signature film The Ear (1970) was banned by the Communists before its release. Both a surrealist and a humanist, Kachyna, like, many of the filmmakers listed, was blacklisted during the subsequent period of so-called normalization, while others like Forman, Nemec, and Passer went into exile.

One of the signature films at the festival is a biopic about Jan Palach (2018) who martyred himself through self-immolation in 1968 in Wenceslaus Square in Prague to protest the invasion of Soviet Russian troops on August 21st, which ended the country’s first attempt to reestablish democracy. Visiting my grandparents for several weeks and only leaving days before the invasion, I remember those heady days, listening late at night to students, workers, and leading politicians discuss the country’s fate in the Old Town Square. Three years later, I was back in Prague, now a young film student, following up on what had happened to the Czech New Wave, which included Oscar winners Miloš Forman, Ivan Passer, as well as Vera Chytlová, Jiři Menzel, Jan Nĕmec, Juraj Herz, and Karel Kachyna, whose signature film The Ear (1970) was banned by the Communists before its release. Both a surrealist and a humanist, Kachyna, like, many of the filmmakers listed, was blacklisted during the subsequent period of so-called normalization, while others like Forman, Nemec, and Passer went into exile.

Another film in the series, Golden Sting (2018), visualizes Czech history between 1938 and 1948, a period when my dad survived incarceration in a Nazi concentration camp, was involved in the Resistance movement, and ran for political office after the liberation, only to see the hopes for democracy crushed by a Communist putsch. The films in Czech That Film are therefore worthy of attention, because they connect to the fates of living human beings, their stories relevant especially today, when democracies all over the world are again in peril.”

Watching Golden Sting on opening night, I was constantly reminded of the fate of my dad and grandparents, although the film is ostensibly the story of the Czech national basketball team, which against all odds won the European Championship in 1946 in Geneva. The hero of the film is an upper-middle-class kid, Franta (Filip Březina), who with his teammates learns basketball from American Mormons in the late 1930s. They continue to train after the Nazi occupation in 1939, but their coach (Ondrej Malý) is killed by the Germans in 1942, so Franta takes over coaching duties. After winning in Geneva, they lose in the 1948 Olympics in London, then go to the European Championships in Paris in 1950, where they come within a point of beating the Russians, who score a free throw with one foot over the line. The referee asks whether the Czechs will protest, offering them overtime and a chance to win, if they do. But things had changed, because the Communists were now firmly in control and Franta was in prison, so the new coach states that the Czech nation will never protest against the Soviet Union, thus throwing the game. The Czechs and Slovaks would continue to “offer” their national wealth to the Soviets for the next 40 years.

The film received mixed reviews in the Czech press, but for me there were chilling moments in the film. When the coach is murdered in retaliation for the May 1942 assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, I had to think of my great uncle, General Josef Kohoutek, who was executed on August 19, 1942 in Plötzensee (Berlin), because he was the head of Czech Army Intelligence. Or when Franta and his dad, a government minister, look out the window of a shop and see a phalanx of Communist militia in red armbands and rifles march through the streets of Prague, the beginning of the February 1948 putsch that sent my dad into exile. In another scene we see Franta’s house invaded by the secret police in the middle of the night; a short time later, the family has moved into the basement of their spacious villa, while “deserving workers” are billeted above. It made me realize how my grandfather, who had been the CEO of ČKD, one of the nation’s largest manufacturing companies, must have felt when his family was reduced to three small rooms in their 15-room house in Vysočany (pictured, right). I vividly remember the walls were covered floor to ceiling with paintings that had previously hung in the whole house. My aunt Libuše, who was born in the house in 1929, the year after my great-grandfather built it, never moved out of those crowded rooms, although she did regain control of the property in the 1990s.

The film received mixed reviews in the Czech press, but for me there were chilling moments in the film. When the coach is murdered in retaliation for the May 1942 assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, I had to think of my great uncle, General Josef Kohoutek, who was executed on August 19, 1942 in Plötzensee (Berlin), because he was the head of Czech Army Intelligence. Or when Franta and his dad, a government minister, look out the window of a shop and see a phalanx of Communist militia in red armbands and rifles march through the streets of Prague, the beginning of the February 1948 putsch that sent my dad into exile. In another scene we see Franta’s house invaded by the secret police in the middle of the night; a short time later, the family has moved into the basement of their spacious villa, while “deserving workers” are billeted above. It made me realize how my grandfather, who had been the CEO of ČKD, one of the nation’s largest manufacturing companies, must have felt when his family was reduced to three small rooms in their 15-room house in Vysočany (pictured, right). I vividly remember the walls were covered floor to ceiling with paintings that had previously hung in the whole house. My aunt Libuše, who was born in the house in 1929, the year after my great-grandfather built it, never moved out of those crowded rooms, although she did regain control of the property in the 1990s.

< Back to the Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation