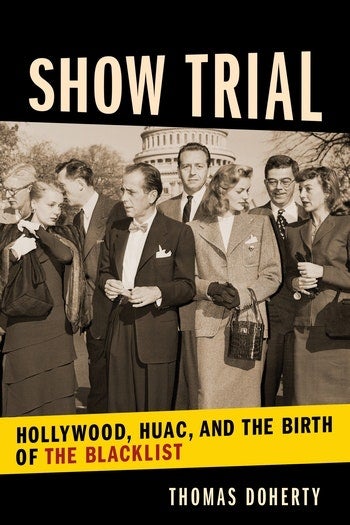

Lauren Bacall and Humphrey Bogart leading the Committee for the First Amendment in Washington, D.C. in October 1947

The number of historical studies of the Hollywood blacklist continues to expand. Prominent examples include Victor S. Navasky’s Naming Names (1980), Larry Ceplair and Steven Englund’s The Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics in the Film Community (1980), Bernard F. Dick’s Radical Innocence: A Critical Study of the Hollywood Ten (1989), and Patrick McGilligan and Paul Buhle’s Tender Comrades: A Backstory of the Hollywood Blacklist (1999), as well as memoirs from many of the victims. Thomas Doherty, who has previously published Cold War, Cool Medium: Television, McCarthyism, and American Culture (2003), has now offered a blow-by-blow study that specifically focuses on the first House Un-American Activities hearings in 1947 into alleged Communist infiltration of Hollywood.

Relying on original documents, film recordings and transcripts, rather than after-the-fact memories of the participants, Doherty’s narrative in Show Trial is fast-paced and immediate, giving a strong sense of the events as they transpired. In the first five chapters, “Backstories,” Doherty reviews the events that led to the HUAC hearings: the Hollywood writers’ wars, unionization of the animation crafts, the popular front, the first aborted HUAC hearings of Martin Dies’ committee in 1940, and the film industry’s record of producing anti-Nazi propaganda films as a part of the effort to win World War II. The first hearings failed not only because Hollywood presented a united front against congressional interference, but also because committee co-chair John E. Rankin was an overt racist and a virulent anti-Semite.

“On Location in Washington” covers the next nine chapters, and presents a day-by-day analysis of the hearings that commenced on October 20, 1947. Doherty makes clear from the outset that this was a “show trial,” similar to those held in Moscow in the 1930s: Representative J. Parnell Thomas “refused to permit lawyers to coach or advise their clients, although consultations between attorneys and clients were usually permitted in congressional hearings. He allowed some witnesses, usually the Friendlies, to read opening statements, but denied the right to others, usually the Unfriendlies. The hearing was too public to be a star chamber and too open-ended to be a kangaroo court, but it was not a judicial proceeding either. It was a bastard hybrid, part show, part trial” (p. 105). Beginning with a short biography of the witness, and a pregnant quote as lead-off, each speaker’s testimony is described in a couple of pages. Friendly witnesses included studio heads, Jack Warner, Louis B. Mayer, Walt Disney, actors Adolphe Menjou, Robert Taylor, Robert Montgomery, George Murphy, Ronald Reagan and Gary Cooper, directors Leo McCarey and Fred Niblo, Jr., and a host of other lesser lights, most enthusiastic and naming names, some less so, like Cooper who mumbled his way through his performance, admitting he didn’t like Communism, “because it isn’t on the level” (p. 171).

“On Location in Washington” covers the next nine chapters, and presents a day-by-day analysis of the hearings that commenced on October 20, 1947. Doherty makes clear from the outset that this was a “show trial,” similar to those held in Moscow in the 1930s: Representative J. Parnell Thomas “refused to permit lawyers to coach or advise their clients, although consultations between attorneys and clients were usually permitted in congressional hearings. He allowed some witnesses, usually the Friendlies, to read opening statements, but denied the right to others, usually the Unfriendlies. The hearing was too public to be a star chamber and too open-ended to be a kangaroo court, but it was not a judicial proceeding either. It was a bastard hybrid, part show, part trial” (p. 105). Beginning with a short biography of the witness, and a pregnant quote as lead-off, each speaker’s testimony is described in a couple of pages. Friendly witnesses included studio heads, Jack Warner, Louis B. Mayer, Walt Disney, actors Adolphe Menjou, Robert Taylor, Robert Montgomery, George Murphy, Ronald Reagan and Gary Cooper, directors Leo McCarey and Fred Niblo, Jr., and a host of other lesser lights, most enthusiastic and naming names, some less so, like Cooper who mumbled his way through his performance, admitting he didn’t like Communism, “because it isn’t on the level” (p. 171).

Before moving on to the “Unfriendly Nineteen” (some of whom were never called, thus reducing the group to the “Hollywood Ten”), the screenwriters and directors who were eventually sent to prison for contempt of Congress, Doherty spends a chapter on the Committee for the First Amendment, a group of Hollywood liberals who travelled to Washington to protest the hearings, led by Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Edward G. Robinson, Danny Kaye, Marsha Hunt, Paul Henreid, John Huston and William Wyler. They made a lot of noise outside the House chamber, naturally drawing lots of press attention, but also wanted to emphasize that they did not support Communist beliefs. Eventually, as Doherty enumerates in the final quarter of the book, “Backfire,” many recanted their support in the face of the MPAA’s Waldorf statement and rising anti-Communism.

The HUAC fireworks really started with John Howard Lawson, a well-known CPUSA party leader and very highly paid screenwriter who, like Dalton Trumbo, Albert Maltz and Alvah Bessie, was gaveled into silence and forcibly removed from the chamber after insisting on his First Amendment rights and refusing to admit he was a Communist. Chairman Thomas broke a couple of gavels in the process, especially when Samuel Ornitz brought up the question of anti-Semitism, given that many of the “Hollywood Ten” were Jewish. By the ninth day of the hearings, HUAC had become so efficient at asking the $ 64,000 question, “Are you or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?” that Lester Cole’s testimony lasted a mere 6 ½ minutes before he was escorted out by Capitol police.

The HUAC hearings of 1947 ended with a victory for the Bill of Rights, because the Committee failed to prove that Communists ran Hollywood, but that victory was turned into defeat when the motion picture producers caved to perceived public pressure—unlike in 1940—and released the Waldorf statement that instituted the Blacklist against anyone who was a Communist or Communist sympathizer. Fearful of box office losses at a moment when they were about to lose their monopoly, due to the Paramount Consent Decree, they betrayed their best talent, then knowingly rehired them through fronts at a third of the cost. Trumbo would win two Oscars under pseudonyms. Hundreds were blacklisted, many not working for more than a decade.

For all its specificity, this book reveals little new information about the Hollywood HUAC hearings, but it does offer an excellent introduction to the topic for a younger generation who may not have known that the Trump era is not the first in U.S. history to play fast and loose with the Constitution.

< Back to the Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation