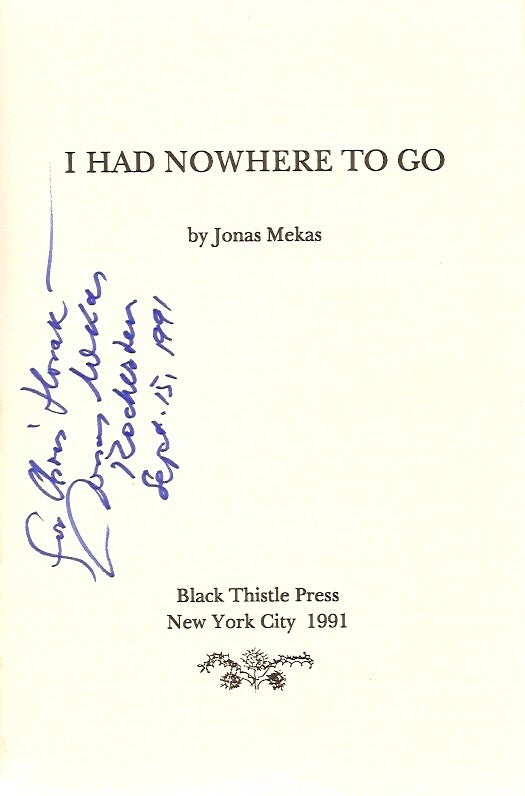

Jonas Mekas, one of the most famous American film avant-gardists of the 20th century, has died. I first met Mekas when I was a student more than 40 years ago, and we remained friendly archive colleagues over the years, although he disapproved of my revision of American avant-garde film history in Lovers of Cinema: The First American Film Avant-Garde. For me, he was a father figure, not only because of our mutual interest in avant-garde cinema, but also because of our similar origins. Mekas was a year younger than my dad, and spent the immediate postwar period in a displaced persons camp in Germany, as did my family. The early scenes of New York in Jonas’ Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania (1972) reminded me of my own childhood among Czech exiles in Chicago, but, interestingly, his four and a half years in a displaced persons (DP) camp is not addressed in the film, nor in any other of his diary films. However, Mekas’ published autobiography, I Had Nowhere to Go (1991), does cover his lost years before his immigration to New York.

Jonas Mekas wrote in his diary in December 1951: “I have tried. I have done everything to be just like everybody else. I have tried to be down to earth. Digging my hands deep into the sand pile on Sixth Avenue. Touching the ground in Central Park with my bare feet. But I remain a stranger here.” Like my parents, he was a stranger in a strange land, a displaced person, cast adrift in an alien culture. And yet, there are surprisingly few passages in I Had Nowhere to Go in which Mekas nostalgically reminisces about his childhood in Lithuania. Instead, two obsessions dominate. The daily struggle for food and shelter, since the rations supplied by the International Relief Organizations were never enough, and Mekas’ bibliophilia. Of his obsessive preoccupation with food, Mekas writes: “I’m ashamed of how much space in my diaries I am giving to what we eat. To the stomach. I know many a reader will put me down, because of that. But that is the reality of our lives, these days. You try to stick to the spirit, but the stomach wins.”

Jonas Mekas wrote in his diary in December 1951: “I have tried. I have done everything to be just like everybody else. I have tried to be down to earth. Digging my hands deep into the sand pile on Sixth Avenue. Touching the ground in Central Park with my bare feet. But I remain a stranger here.” Like my parents, he was a stranger in a strange land, a displaced person, cast adrift in an alien culture. And yet, there are surprisingly few passages in I Had Nowhere to Go in which Mekas nostalgically reminisces about his childhood in Lithuania. Instead, two obsessions dominate. The daily struggle for food and shelter, since the rations supplied by the International Relief Organizations were never enough, and Mekas’ bibliophilia. Of his obsessive preoccupation with food, Mekas writes: “I’m ashamed of how much space in my diaries I am giving to what we eat. To the stomach. I know many a reader will put me down, because of that. But that is the reality of our lives, these days. You try to stick to the spirit, but the stomach wins.”

Apart from Mekas’ awareness of his dietary needs, this quote is interesting because it exemplifies the fact that Mekas is not just writing a diary for himself, rather, even at this early date he is writing as a poet, as a writer, as an artist who will one day publish his diary. From the introductory pages of the autobiography we know that Mekas and his brother Adolphas identified themselves as poets, even before they left Lithuania, and certainly in the period they were in the displaced persons camp. It was that largely imaginary identity that kept them from the noose (seen hanging at the beginning of Reminiscences), kept them from falling too deeply into despair. While others take jobs in the camps, they sit and read, they write poetry and diaries, they discuss literature. Mekas writes in November 1947: “Everybody’s signing up for Canada. Mostly they are looking for tailors, shoemakers, professions like that. No requests for poets yet.”

Certainly, Mekas was a reader. In July 1945, a mere four months after their escape from a Nazi-forced labor camp, Mekas tells us that he and his brother are schlepping over a hundred books with them. When they arrive in Wiesbaden at a new DP camp, the American MPs are perplexed: “They open one bag – books. The open another – books… They open suitcases – more books. ‘Where are your things?‘ one asks. ‘We have no things,’ we say. We point at our books, we say these are our things. They look at us as one looks at the insane…” When the brothers embark on the steamship that will take them to America in October 1949, they are carrying merely one small suitcase and over 500lbs of books in nine crates!

Certainly, Mekas was a reader. In July 1945, a mere four months after their escape from a Nazi-forced labor camp, Mekas tells us that he and his brother are schlepping over a hundred books with them. When they arrive in Wiesbaden at a new DP camp, the American MPs are perplexed: “They open one bag – books. The open another – books… They open suitcases – more books. ‘Where are your things?‘ one asks. ‘We have no things,’ we say. We point at our books, we say these are our things. They look at us as one looks at the insane…” When the brothers embark on the steamship that will take them to America in October 1949, they are carrying merely one small suitcase and over 500lbs of books in nine crates!

In the DP camps Mekas spends a lot of time and spare change going to the movies. In his diaries, he occasionally lists his likes and dislikes. The first mention of film is October 1945, when Mekas sees Chaplin’s The Gold Rush. In November 1947 he sees Wir machen Musik, a German musical from 1942 that bores him, so he leaves after half an hour.A day later he writes: “Movies here (in Mainz) are old, bad German movies. In Wiesbaden we saw Gaslight, a little bit better.”

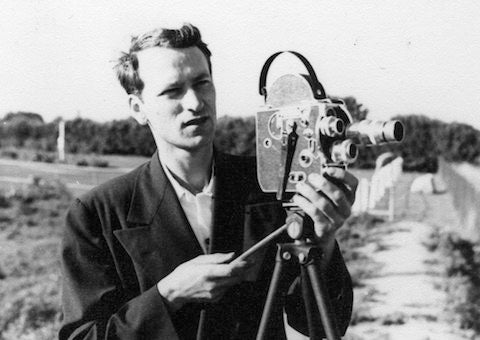

I suspect that even without the chaos of war, Mekas would have eventually moved from the familial hearth to lead the life of an artist, whether in Berlin, Vienna or New York. In America, he works menial jobs because, as he states repeatedly, he doesn’t want a profession. His profession is that of an artist. Less than six months after arriving in New York, he and his brother begin filming with a borrowed camera and no money. Their friends think they are crazy. As a romantic, Mekas believes that artists must be mad. When they finally succeed, it is not only their integration as DPs into the American avant-garde that is at stake, but also the realization of long-standing ambitions as artists. Indeed, his alienation as a DP led him to the film avant-garde, where he remained a champion of outsiders and persons at the margins in the film world. As his many obituaries document, we all owe him a debt of gratitude for his work.

You can learn more about Mekas’ Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania and my own biography here.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation