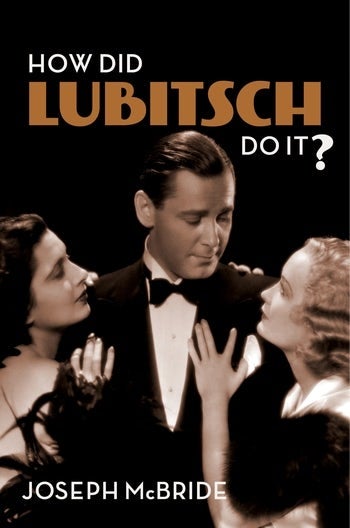

Ernst Lubitsch and the cast of Design for Living (1932)

We opened our highly successful summer film series, How Did Lubitsch Do It?, with a book signing for Joseph McBride’s tome of the same title. In a recent blog on the series, I noted I would review McBride’s study, which has received uniformly excellent reviews.

Joseph McBride initially makes the case that, unlike Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles and John Ford, Ernst Lubitsch has been forgotten in the public mind, even though he may actually be the greatest American director of the 20th century. He was not only a Hollywood film auteur, he had previously risen to the top in Berlin, where he helped establish the German film industry in the post-World War I era. What made Lubitsch great was his modernity, his sophistication, his willingness to tackle complicated, adult themes like love, sex, marriage and infidelity, without resorting to the kinds of moralistic clichés that plagued classical Hollywood. In discussing a key scene from Lubitsch’s masterpiece, Trouble in Paradise (1932), McBride writes: “This exquisitely moving scene is a consummate example of Lubitsch’s mingling of romance and regret, tenderness and pain. It is an exchange that shows how he could evoke the complex interplay of seriocomic human emotions better than almost any other director” (p. 33).

Rather than writing a biography—although there is also much biographical information here—McBride’s goal was to write a critical study of Lubitsch’s films, in the hopes that they are revived more frequently and find new audiences. And in contrast to much of the academic literature on Lubitsch, McBride analyzes the German and American periods in relation to each other, rather than as whole separate phases of his career. Given the negative assessment of Lotte Eisner of Lubitsch’s early German films, it seemed important for McBride to demonstrate that the German period was not merely an apprenticeship, but that some of that work holds up to critical standards, even today.

Eisner, who came from West Berlin’s Jewish haute bourgeoisie, was actually embarrassed by the broad, Jewish humor of East Berlin, populated by recent immigrants from the shtetl, including Lubitsch’s own family: his father had come from Grodno (Belarus). McBride frames the work in terms of Lubitsch’s changing attitude to his acting, since Lubitsch was the star of his first comedies, like Schuhpalast Pinkus (Shoe Salon Pinkus, 1916), but increasingly harbored (justified) doubts about his acting ability. But McBride also notes that these films have been read in recent times as anti-Semitic, although he argues that Lubitsch actually played with Jewish stereotypes, because it was “a matter of fun” (p. 76) and out of a deep sense of affection for Jewish characters attempting to circumvent ethnic social boundaries (like himself).

More importantly, McBride doesn’t bifurcate the comedies and the more famous historical dramas, seeing strong doses of irony in the latter, which would become part and parcel of the “Berlin style” that would characterize his American work: “That approach includes a tolerant detachment toward human failings, which is among his most admirable qualities in his refusal to judge people in conventionally moralistic terms” (p. 116). McBride considers The Oyster Princess (1919) to be Lubitsch’s first comedy masterpiece.

Of Lubitsch’s American silents, McBride declares The Marriage Circle (1924) and Lady Windermere’s Fan (1925) to be absolute masterpieces, but also attempts to rehabilitate Rosita (1923) as a good but not great film; Mary Pickford, the star and producer, hated it to the point of having negatives and existing prints destroyed.

The Love Parade (1929)

But McBride reserves his most extravagant praise for Lubitsch’s pre-Code comedies from The Love Parade (1929) to The Merry Widow (1934), discussing the “pure cinema” of Lubitsch’s editing and composition that highlights gestures, looks and body language, to create subtle portraits of human dilemmas in love, marriage and infidelity. Once the Breen Office clamped down on censorship, Lubitsch retreated from the bawdy, sexual banter of films like The Smiling Lieutenant (1931) to a much more conventional “invisible” Hollywood style that avoided overt expressions of sexual desire. Nevertheless, Lubitsch would still have at least three more great films in his future, Ninotchka (1939) with Greta Garbo; The Shop Around the Corner (1939), his elegiac look at a culture that would soon disappear in the Holocaust; and To Be or Not to Be (1942). The latter film, an anti-Nazi comedy about the invasion of Poland that dared to mix comedy and drama, was thoroughly misunderstood at the time of its release, but is now considered one of the director’s most subtle political critiques.

Lubitsch and his frequent star Maurice Chevalier

McBride’s résumé of Lubitsch’s career is sobering. While Billy Wilder carried on the Lubitsch tradition, McBride sees a dumbing-down and vulgarization of comedy in the last 30-plus years: “Lubitsch’s often-unorthodox treatment of sexuality is far more daring than the kind of sophomoric stuff that passes for audacity today.” McBride, of course, understands there are multifarious reasons for this modern state of affairs, but he does harbor the hope that we can still produce films “that are more about people than special effects, more focused on narrative than spectacle…” (p. 478). If nothing else, we, like Joseph McBride, can console ourselves with the Lubitsch films still in our midst.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation

Comments