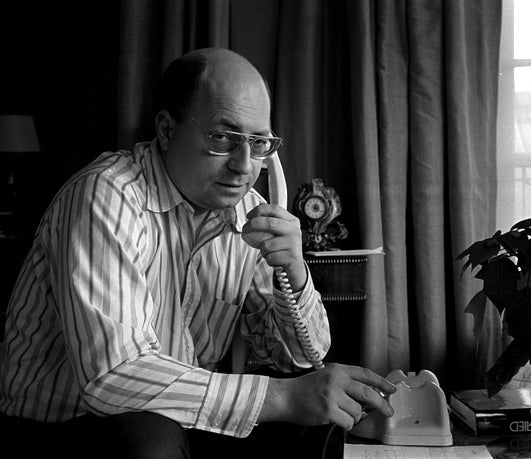

Yung Hee Rissient sent me an email about the death of her husband a few days after his passing on May 5th, but somehow I missed it, at least until I started seeing obituaries more than a week later, including Bernard Tavernier’s moving tribute. To me, Pierre was a mysterious giant of cinema, who seemingly knew tout le monde, turned up everywhere, and could quote scenes from the most obscure American B-films. At the same time, it was always a bit unclear to me, what role he actually played. I knew he had a home in Paris, but to me he was a kind of cinema luftmensch.

Critic and filmmaker Todd McCarthy probably captured the spirit of Pierre Rissient best in the documentary he made in 2007, Pierre Rissient: Man of Cinema, where Claude Chabrol, Michel Ciment, Clint Eastwood, John Boorman, Werner Herzog, Hou Hsiao-Hsien, among others, are interviewed about Pierre’s huge behind-the-scenes role at the Cannes Film Festival. Attending out-of-the-way film festivals around the world, Pierre would return to France and report back to the Cannes leadership that he had discovered another major unknown auteur. Indeed, the last time I saw Pierre was a couple of months ago at the Guadalajara film festival, which I was attending for the first time. We stayed at the same hotel, so had breakfast together a couple times. Pierre was gregarious and effusive as ever, but had become very frail and was in a wheel chair.

I first met Pierre in the late 1980s, when I was Curator at George Eastman Museum in Rochester. He had come to the museum to do some research on Lubitsch, whom he loved; he reminded me at our last meeting, because I was then planning a Lubitsch retrospective. We went out to dinner and my memory of our conversation was that we played what I thought was a French parlor game for film critics, trying to name the most obscure film of greatness by a Hollywood director that the other person hasn’t seen: “Chrees, half you sin de Toth’s Crime Wave?” For 30-plus years, we played, whether in Rochester, Munich, Berlin or L.A., and Pierre always won. He was a virtual encyclopedia, who could quote scenes by heart from just about every film he had ever seen.

But, as Bernard Tavernier reports in his remembrance of Pierre in Film Comment, Rissient could be uncompromising and indeed made many enemies. He also had his blind spots. I was shocked to hear him say that Alice Guy-Blaché  was a director of no consequence and only made bad films, when he was interviewed by Pamela Green for her documentary, Be Natural: The Untold Story Of Alice Guy-Blaché (2018), which coincidentally premiered at Cannes the day after Pierre died.

was a director of no consequence and only made bad films, when he was interviewed by Pamela Green for her documentary, Be Natural: The Untold Story Of Alice Guy-Blaché (2018), which coincidentally premiered at Cannes the day after Pierre died.

Pierre Rissient was born on August 4, 1936 in Paris. He came from a lower middle class background and fell in love with movies while in high school. He started law school, but the sway of cinema was stronger. He was soon working for the Mac Mahon cinema in Paris, which still exists today near the Arc de Triomphe, programming films and finding unknown titles to distribute and promote. He also dabbled in filmmaking, becoming an assistant director for Jean-Luc Godard on Breathless (1960), and much later directing two films himself, Alibis/One Night Stand (1977), which he shot in Hong Kong, and Cinq et la peau / Five and the Skin (1982), which he shot in the Philippines with Féodor Atkine. Neither film made much of a splash.

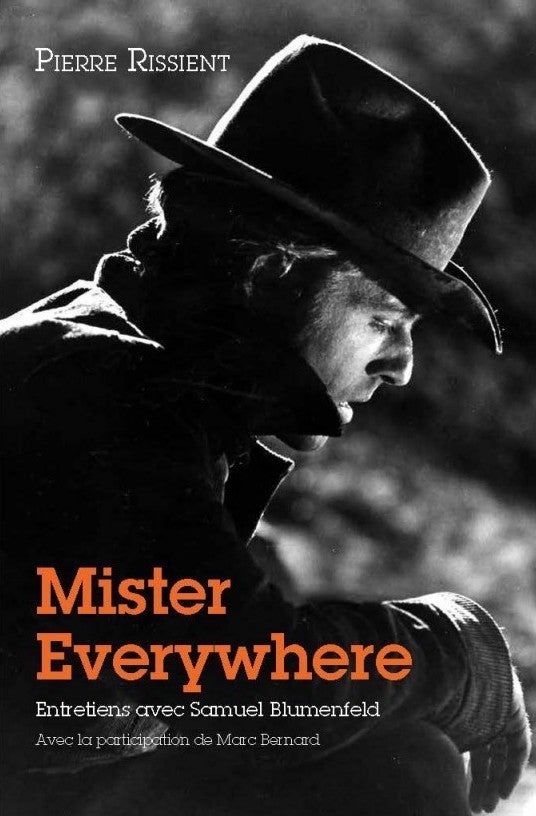

But, as many have noted, Pierre’s real claim to fame was as a roving film critic, who promoted the films and directors he loved by talking about them. He was the first to champion Clint Eastwood as a director, not just an actor in Westerns. According to Tavernier, he also brought Martin Scorsese, Abbas Kiarostami, Lino Brocka and Jane Campion to Cannes. A French book of interviews by Samuel Blumenfeld with Rissient is called Mister Everywhere (2016).

I will miss our dinner games.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation