If you watch television news, you’ve probably noticed the ever more intense urgency with which the PSAs of wildlife organizations are pleading with the public to save snow leopards, elephants, and other wildlife. That same advocacy can be seen in animal documentaries, but with a difference. For more than 100 years, filmed images of the natural world conformed to the classic documentary aesthetic. Such images were perceived to be an expansion of human vision, a means of entering into a world that was invisible to the human eye, an extension of the physical body of the viewer, allowing for the creation of pleasure by bringing animals in their natural habitat closer to humans. And while the visualization of animal life entailed particular narrative conventions that also communicated overt and covert ideologies, as is the case with all documentary forms, audiences still believed in the iconic nature of that experience. We are now observing a paradigm shift in the use of wildlife films. Today, the impulse to document nature is augmented by the much higher-stakes endeavor of “preserving” animal life in a virtual world. Looking over the precipice of an earth depopulated of its wildlife, the goal of nature filmmakers becomes the capture of animals in images. Every moving image can potentially be the last “living” image of a species, in the truest sense of the word.

We can compare this phenomenon in the natural world to the work of Edward S. Curtis, the photographer and documentary filmmaker who made it his duty to document Native American cultures in North America before they became extinct. Curtis was convinced of his mission to photochemically preserve a “dying race” through images. Human societies living close to nature were indeed the first victims of modernization and the capitalist exploitation of natural resources, although Native Americans are far from extinct.

Soon, our culture may possibly only see wild animals virtually or in special game reserves and zoo. Michel Foucault in a lecture defined zoological and botanical gardens as “heterotopias.” In these “other spaces,” whether real or virtual, as in wildlife films, wildlife has been collected ordered, and systematized “to create a space that is other, another real space, as perfect, as meticulous, as well arranged as ours is messy, ill constructed, and jumbled.”

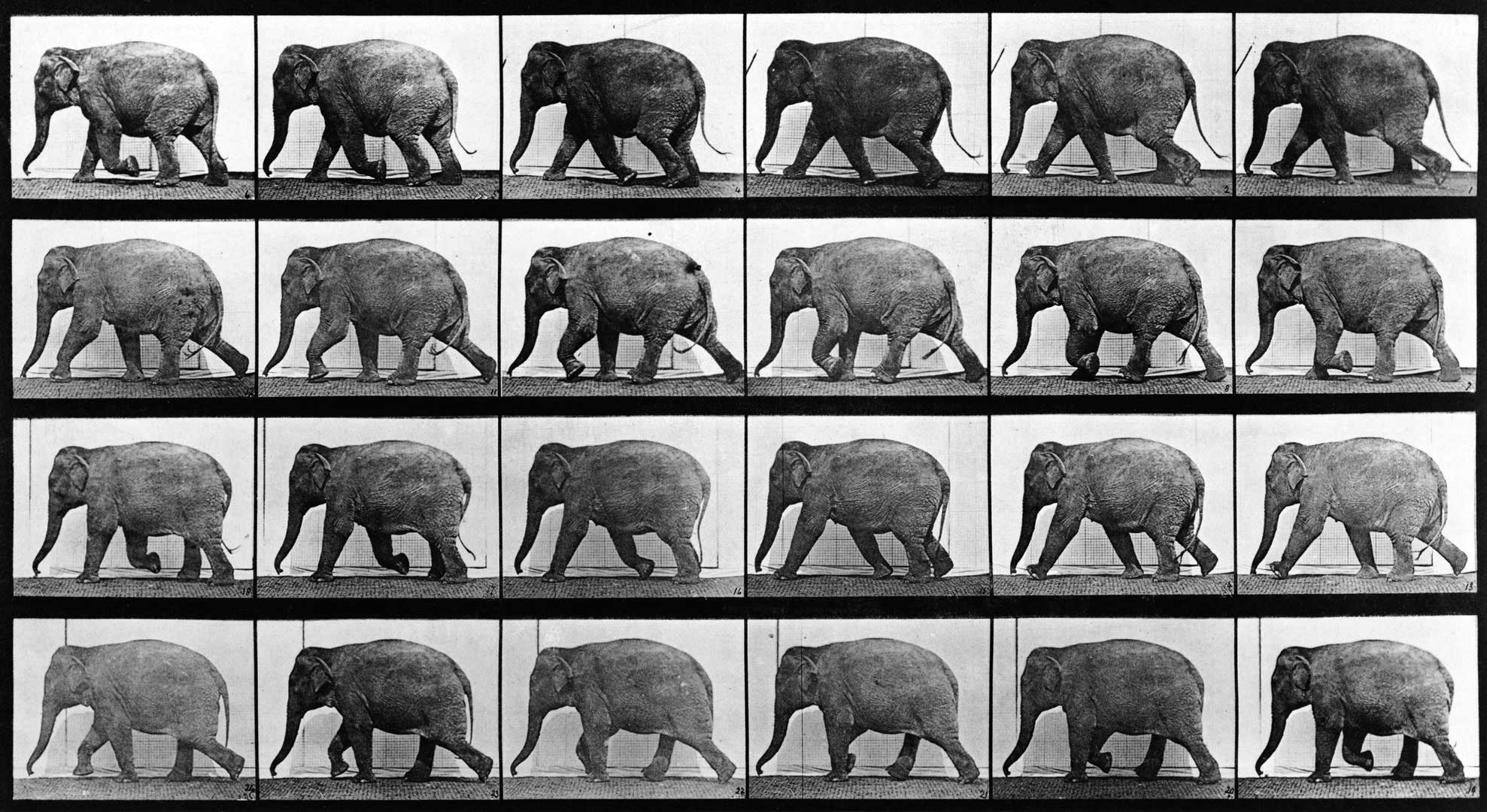

Eadward Muybridge circa 1887.

As a casual subject of moving images, animals have been present ever since Eadweard Muybridge photographed his animal locomotion series. Yet within classical documentary forms, animals have seemingly remained confined to the scientific and educational sphere, only intermittently the subject of a mainstream theatrical experience. With the introduction of television and cable, with its insatiable demand for content, wildlife documentaries have become ever more popular and ever more numerous. Countless animal film festivals are in operation these days, giving animal lovers, ecology freaks, and the moviegoing public an opportunity to commune with nature. The production of animal films for television has expanded with the establishment of cable channels, e.g. Animal Planet, National Geographic, and Discovery. These networks broadcast animal documentaries almost 24 hours a day.

In crass opposition to the insatiable fascination that viewers bring to the experience of viewing wildlife films, the rate at which animals are becoming extinct is accelerating; they’re victims of a civilization that places little value on natural habitats. The quicker humanity ruins the natural environment through deforestation and the establishment of urban centers in previously untouched areas, the more rapidly certain species expire. According to the ongoing surveys of the International Union for Conservation of Nature, the so-called “Red Lists,” more than 16,119 species are threatened with extinction, including 1,003 kinds of mammals, i.e. 20%. Also endangered are 31% of all amphibians, 12% of all bird species, 4% of all reptiles, and 4% of all fish. In the United States, 236 animal species have already become extinct. Particularly at risk are our closest relatives in the animal world, the primates: of the world’s 296 primate species, 114 are critically endangered.

One can therefore legitimately ask whether the growing obsession to document visually the animal world isn’t at least partially a desperate act to “save” wildlife for a virtual world. Certainly an appeal to viewers to actively participate in preserving the natural environment is a narrative element in many modern wildlife documentaries, but these are usually depoliticized, calling for individual action, rather than social struggle. The urgency with which “the end of nature” is present in the master narratives of many recent wildlife documentaries indicates that the worst fears of humanity are no longer unthinkable and may even become a reality. Animal film producers are seemingly preparing the public for the day when all wildlife will merely be seen in zoos, wildlife reserves, aquaria or virtually as moving images.

With the Trump administration’s wholesale assault on the environment and its opening of wildlife preserves to commercial activity, this trend will only accelerate.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation