Digitized home movie from the Prelinger Archives

On April 6, professor Shawn VanCour of the UCLA Graduate School of Education & Information Studies invited a group of scholars to campus for the Visiting Speaker Series on Issues in Digital Archiving. The participants on a panel on legal and ethical issues were Kim Christen (Washington State University), Kenneth D. Crews (Munich Intellectual Property Law Center), David Pierce (Library of Congress) and Rick Prelinger (Prelinger Archives, UC Santa Cruz). After their individual talks, Maureen Russell (UCLA Ethnomusicology Archive) and I were invited to the stage for a roundtable discussion.

David Pierce began the proceedings, discussing the Library of Congress Motion Picture Division’s policy on streaming, noting that their efforts have been hampered in the past by their legacy deposit agreements, some of which do not allow for any access whatsoever without approval from the copyright depositor. As a result, the LoC no longer accepts any material on deposit, and actually asks donors to contribute to processing costs. Pierce also differentiated between online access and streaming on premises, the former only possible with permission from the copyright holder.

A selection of films made available online by the Library of Congress

Unlike the Library of Congress, which has to take a very careful approach to copyright, Rick Prelinger has been advocating for a more liberal view, noting that there are limits to legalistic thinking. He noted that by the end of 2017, YouTube had uploaded seven billion videos. And yet, there is not a lot of commonality between rights holders, digital repositories and archives. Prelinger has been putting his collection of orphaned works online, even without a contract from the copyright holder, although copyright searches were done. Most home movies are not in the public domain as many people assume, but rather owned by their makers for 125 years after production, although almost no one makes any claims. For Prelinger it is a matter of being respectful, but also working within the ecosystem of copyright and access, which is “what people make of it.”

Next, Kenneth D. Crews, a trained copyright lawyer, discussed copyright law, arguing that copyright protects all original works of authorship that have been fixed on a medium. In other words, only performances cannot be copyrighted. An original work must also have a degree of creativity in its organization, and not just exist as a mass of data, so e.g. the phone book can’t be copyrighted. Crews also argued that fair use is very ambiguous, and it depends on an individual or institution’s risk tolerance, whether they give access to a work that is still under copyright. But access is not ownership. Finally, he noted that other factors might influence copyright access, including privacy and tort laws.

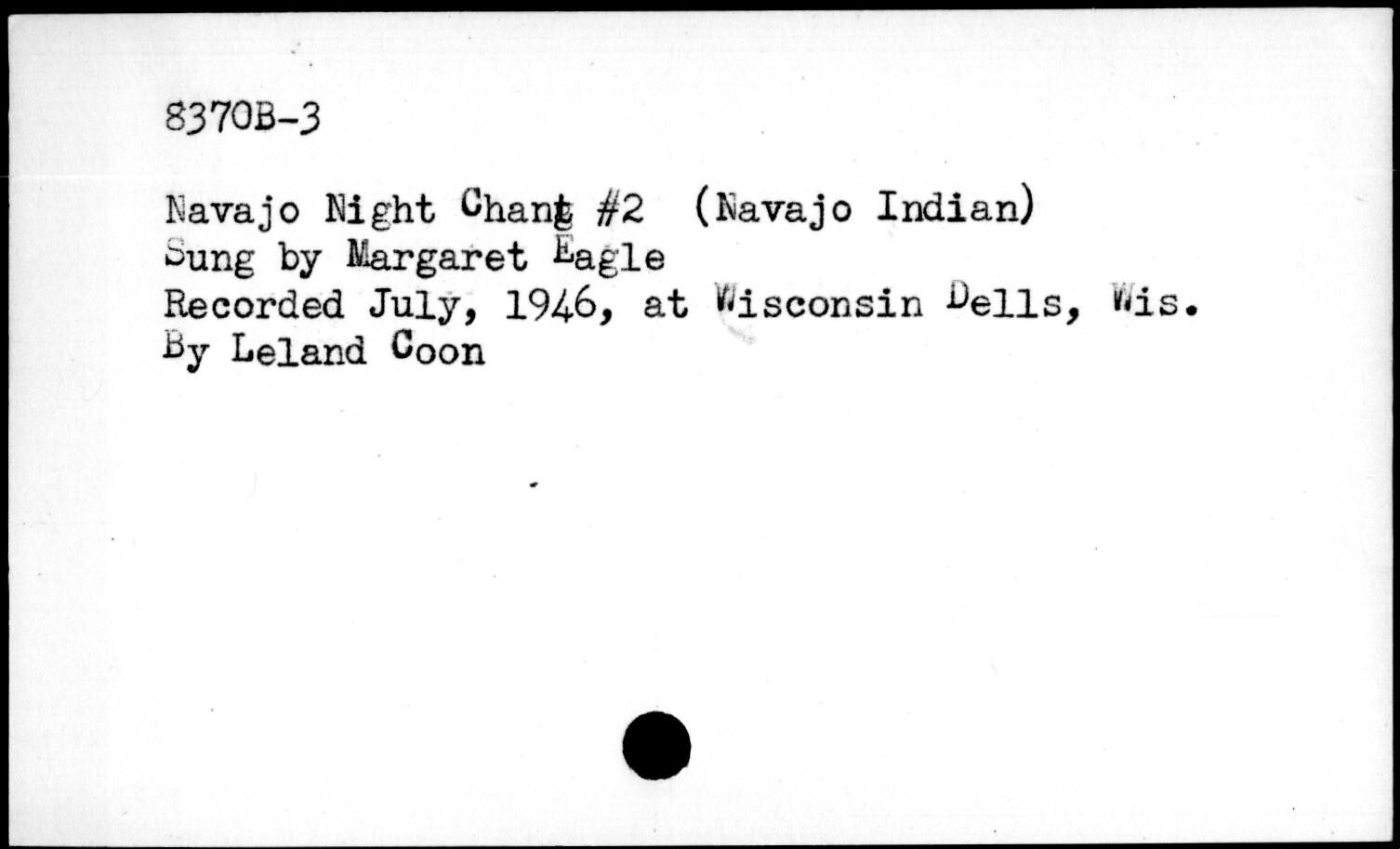

Peabody Museum catalog record

Kim Christen’s presentation addressed access to works created by Native American communities. She argued that colonial circulation routes for gaining access to land and culture often perpetuate theft, when first-world institutions assume that indigenous knowledge can become public domain without the permission of the communities in question. For example, indigenous songs recorded by Harvard’s Peabody Museum are claimed to be owned by the museum, rather than the Native American tribe that sung the works, and are freely circulated. In point of fact, all recordings made before 1972 are PD, according to federal copyright law. Christen, however, has been working on the Local Contexts project, whereby Native American communities learn to manage their own intellectual property. For example, online materials at the Library of Congress are heavily annotated, so as to make transparent the cultural context in which these recordings were produced. Such recordings are then returned to the community for language instruction in native tongues, and for the maintenance of a living native culture and the creation of tribal identities.

A lively discussion ensued around the need of digital archivists to be sensitive to the privacy rights of film subjects, whether Native American communities or home movie families.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation