Nordisk film company

At this year’s Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone, donors received gifts that included Isak Thorsen’s Nordisk Films Kompagni 1906-1924: The Rise and the Fall of the Polar Bear (2017), published as Volume 5 of KINtop Studies in Early Cinema, and edited by Frank Kessler, Sabine Lenk and Martin Loiperdinger. Referred to as the Great Northern Film Co. in the United States, the Danish firm featured a polar bear on its logo, hence the book’s title. Long before Hollywood established its worldwide hegemony or even established a monopoly of film production, distribution and exhibition in this country, Nordisk had created a vertically and horizontally integrated film company in the pre-World War I period, whose only rivals were France's Pathé and Gaumont. And while Richard Abel in a series of books has given us a history of French film developments, no such work had previously been done on the Nordisk, until now. Thorsen’s reworked dissertation, based on research in the company’s intact archives, thus demands attention. His focus on the business of filmmaking, distribution and exhibition demonstrates that the Americans did not originate the classic Hollywood studio system, but rather only improved what the Europeans first invented.

Founded in 1906 by a possibly illiterate film entrepreneur, Ole Olsen, Nordisk was a Copenhagen exhibitor, which also sold its used film prints to other parts of Scandinavia (films were still sold by the foot, rather than rented). Within a year it moved to film production, acquiring a printing laboratory and studio, and by 1910 the company had foreign branches in Berlin, Vienna, New York and London. Between 1906 and 1909, the company’s production output increased from 89 fiction shorts and actualities to 141 films, but more significantly, the number of feet of film sold increased more than five times.

Given the rapid expansion of film production, especially into multi-reel films after 1911, Thorsen makes the point that Nordisk quickly established a factory system of production, which standardized everything from scriptwriting and directing to scene painting: “Whereas the organization of film production in the big French companies developed towards decentralization, Nordisk was based on a centrally controlled, departmental division of labour that looked like, and indeed anticipated, the organization of the American film industry” (p. 145). The company also morphed from a sole proprietorship to a limited company with a board of directors made up of prominent members of Copenhagen’s high society, including representatives from two major banks, this at a time when no American bank would have touched the flickers.

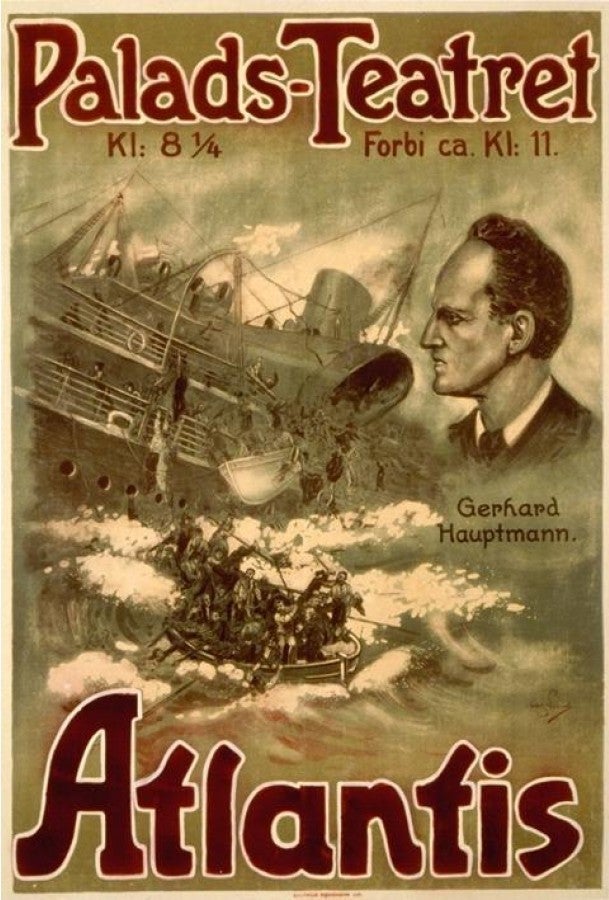

On the other hand, Olsen was disappointed when Nordisk was denied entry into the Motion Picture Patents Company in the United States (the first American attempt at a film monopoly), although it was better served by being a so-called independent, since Nordisk was one of the companies pushing the development of feature films, a shift that the MPPC resisted and led to its demise in 1915. In fact, Nordisk was the first to introduce fiction features in the U.S., releasing a three-reeler in 1911, and Atlantis (dir. August Blom), a film running two hours, in 1913; the Italians followed suit with their cycle of epic films, like Quo Vadis (1913), while American companies were still stuck in short film production.

Longer films also meant retooling the distribution system from selling prints by the foot to renting them on an exclusive basis to a single exhibitor in a given market. Nordisk quickly adapted the “Monopolfilm” system from Germany, where a distributor had rights in a given region, not only joining Germany’s national organization of manufacturers and distributors, but also establishing similar operations in Britain. The reliable quality of Nordisk’s product soon allowed them to force distributors to commit to purchasing rights sight unseen, essentially establishing block booking and blind selling practices which would become central to Hollywood’s later monopoly.

World War I led to Nordisk’s greatest expansion, but ultimately also to its downfall. As a neutral, the Danish Nordisk was perfectly placed to move into the vacuum left by the departing French in the German and Central European film markets, acquiring numerous movie theaters, distributors and film producers. By 1915, the Nordische Film Co., Berlin, controlled many first-run theatres, and distributed films for the Projektions “Union” A.G., one of Germany’s largest film producers, and soon dominated all markets further East. At the same time, its neutral status allowed it to maintain control of the Russian market and still sell films in England and America. When the German government financed the creation of the giant UFA (Universum Film AG) in 1917, Nordisk became a key partner.

The close ties between UFA and Nordisk, however, also led to its downfall after WWI. France, Britain and Russia treated Nordisk as if it had been the enemy, banning their films or confiscating their assets. More importantly, Nordisk’s involvement in UFA during and after the war, led to huge financial losses that ultimately destroyed the company. Here, Thorsen revises a long accepted thesis of Danish film historians that a significant decline in the aesthetic quality of Nordisk’s films led to the company’s demise. That alone is a major accomplishment, but as I have indicated, this publication offers so much more.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation