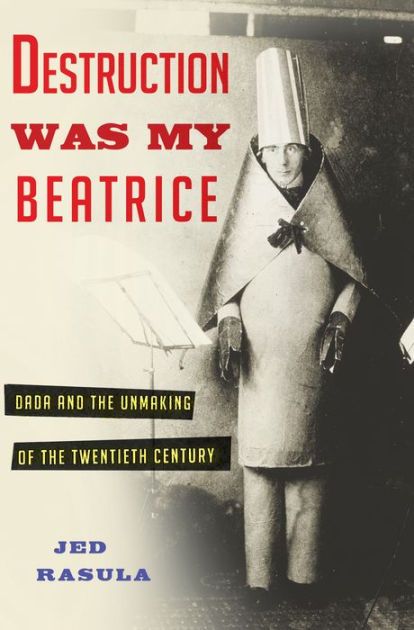

In 1979 I co-curated with my colleague, Ute Eskildsen, an exhibition in Germany, Film und Foto der zwanziger Jahre (Film and Photo in the 1920s), reconstructing a similarly titled exhibition by László Moholy-Nagy and Hans Richter that was seen in Stuttgart, Berlin, Hamburg and Zurich 50 years earlier in 1929. That experience sparked a lifelong interest and academic work in the various art “isms” of the early 20th century, including Constructivism, Dadaism, Futurism and Surrealism, especially as they pertained to photographic media. When I recently discovered that a long-lost high school acquaintance, Jed Rasula, had published an extremely well-reviewed book, Destruction Was My Beatrice: Dada and the Unmaking of the 20th Century (Basic Books, 2015), I was eager to read it.

The book’s title quotes the French Symbolist Stéphane Mallarmé, referring not only to Dante’s muse, but also to Dadaism’s attempts to destroy all traditional notions of art, poetry, literature, criticism and the art market. It was anti-bourgeois, anti-polite society, against good taste and morality, even against itself. “But the real dadas are against DADA,” wrote Tristan Tzara in a poem (p. 176). It was also a provocation, like Marcel Duchamp signing a urinal in 1916 and calling it a work of art, a Dadaist act by an artist who didn’t even know he was a Dadaist. As a result, Dadaism has been often described – most famously by Hans Richter in his book Dada: Art and Anti-Art – as a negation, but what was Dada? Rasula writes: “Dada was a cipher, an invitation to wonder… the meaningless of the word itself enthralled, agitated, and threatened in equal measure” (p. 23). The defining characteristic of Dada was then that it willfully subverted all attempts at definition.

International Dada Fair in Berlin, 1920

Rasula resolves the thorny question by ignoring it, giving us instead a narrative history of Dada as the “virgin microbe,” as Tzara called it, moving from country to country, infecting individuals and institutions. One of the pleasures for me of reading Jed’s book was learning of the interrelationships and back-stories of individuals I knew from my research or just from regular visits to the Museum of Modern Art. Who knew that George Grosz didn’t like Kurt Schwitters? Once, when Schwitters tried to visit Grosz’s studio, he was turned away, Grosz stating: “I’m not Grosz.” (Schwitters left, but came back a few minutes later, informing Grosz “I’m not Schwitters either”) (p. 99). Such laugh-out-loud moments of Dada humor infuse Rasula’s book.

The author begins at what is generally acknowledged as the birth of Dada at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich in 1916, when a group of artists and poets, including Hugo Ball, Richard Huelsenbeck, Marcel Janco Emmy Hennings, Hans Arp, and Tristan Tzara, founded an artist’s cabaret. They were soon joined by Sophie Taeuber, a dancer at the avant-garde Rudolf Laban Academy, and Hans Richter, who like others was a refugee from wartorn Berlin. The troupe read poems, sang songs, performed skits, danced, played piano, while a Russian Balalaika band entertained in between. Much was improvised and all of it was nonsense, poems made of sounds rather than intelligent words, or word poems presented in three languages simultaneously, making any comprehension iffy. Thus, was born dadadada daadaada. Soon, Tzara was publishing a journal, Dada, and a book series.

Next, Richard Huelsenbeck carried Dada to Berlin, where he joined forces with Wieland Herzfelde, John Heartfield and George Grosz to publish the Dada journal New Youth, while Club Dada began organizing Dada evenings. Johannes Baader, Walter Mehring, Raoul Hausmann, Hanna Höch, and Max Ernst quickly joined the Dada movement. “The title ‘artist’ is an insult,” they wrote, thinking of themselves as mechanics or engineers, like the Futurists (p. 66). While Grosz mercilessly attacked the middle class with his caricatures, and Heartfield produced political photomontages, Dada events were calculated to insult audiences; catcalls and riots rather than polite applause, please. Then, there was the outlier Kurt Schwitters in Hannover, a one-man-band who made art out of any trash he could find.

With Tristan Tzara and Hans Arp’s relocation to Paris after World War I, Dada moved to the city of light, where they were greeted by André Breton and Francis Picabia. The Café Certa became the official headquarters of the Parisian Dadaists, as they published manifestos and magazines like Dada and 391, denouncing Dada and organized art exhibitions, e.g. of Max Ernst at the Au Sans Pareil bookstore. They were soon joined by Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, who had spent the war in New York, creating a local Dada scene without the name. Other Dada-influenced initiatives started in the Netherlands, Czech Republic, and even Japan.

Ultimately, Dada would expire or burn itself out. Its end in Paris came on July 6, 1923, when at the Soirée du Coeur à Barbe (where Paul Strand’s Manhatta was screened), Surrealists rioted against Dadaists. But as Rasula notes, its followers would continue under the guise of Constructivism or Surrealism or other -isms, influencing art production throughout the 20th century, whether Fluxus in the 1960s or punk in the 1970s or 21st-century mash-ups of image and sound.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation