Symposium at Rockefeller center in Bellagio, Italy, 1982

Recently the New York Times reported that the Kremlin apparently engaged in a huge cyber campaign to elect Donald Trump and discredit Hillary Clinton, involving not only the release of damaging emails through WikiLeaks, but also by spreading misinformation and propaganda (“fake news” in the words of our President) through numerous social media outlets, such as Facebook and Twitter. Indeed a whole army of stealth bloggers posed as American supporters of Donald Trump, when in fact they were paid Russian hackers. Facebook apparently discovered that between June 2015 and May 2017, 470 fake accounts were set up that produced over 3,000 advertisements that were sympathetic to Trump causes. The Daily Beast also reports that a Russian fronted Facebook group organized anti-immigrant, racist, local Trump rallies. All this activity is associated with a Russian “troll farm,” the so-called Internet Research Agency, which is responsible for disseminating pro-Putin propaganda on the Internet. Such activity is of course illegal for television advertising, according to American campaign finance laws, which require a candidate to approve a message, but on the World Wide Web there are no such restrictive parameters.

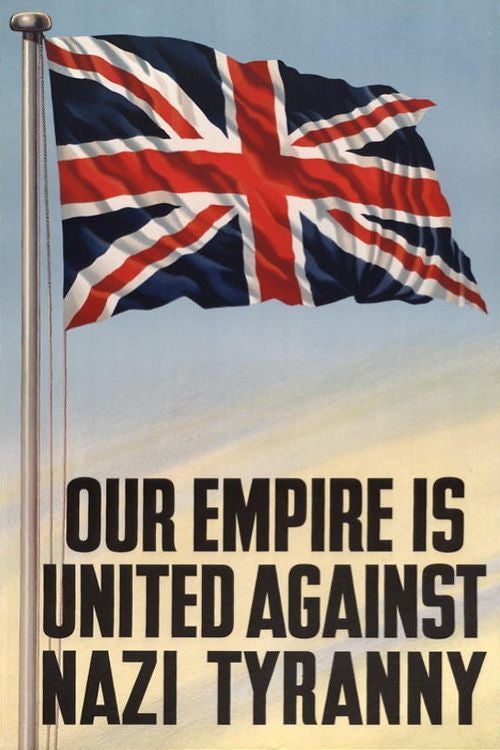

When an information source spreads content through the media, hiding its actual identity, and claiming to be a friend of one group, when they are actually working for someone else, it is called “black propaganda.” It allows an entity to spread lies and rumors without its intended audience understanding the source, making it susceptible to believing that it is coming from a friend rather than a foe. Social media and the internet have of course made it much easier to vilify and embarrass almost anyone, without revealing your own identity. Governments have in the past engaged in black propaganda, when they want to say something that is against policy or make a source credible, when it isn’t. Black propaganda is nothing new. Rather, it was developed as a tool during World War II by the British and Americans to combat the Nazis. Headquartered at the Ministry of Information’s (MOI) top secret facility in Woburn Abbey, Bedfordshire, the Political Warfare Executive (PWE) staff was sworn to secrecy forever, just like the British code breakers in Bletchley Park. This became clear to me, watching the BBC series, The Bletchley Circle (2012) (which features amazing female characters), where former members of the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) refuse to acknowledge their work, even years after the war. It also helped me understand an “incident” I was involved in as a graduate student.

When an information source spreads content through the media, hiding its actual identity, and claiming to be a friend of one group, when they are actually working for someone else, it is called “black propaganda.” It allows an entity to spread lies and rumors without its intended audience understanding the source, making it susceptible to believing that it is coming from a friend rather than a foe. Social media and the internet have of course made it much easier to vilify and embarrass almost anyone, without revealing your own identity. Governments have in the past engaged in black propaganda, when they want to say something that is against policy or make a source credible, when it isn’t. Black propaganda is nothing new. Rather, it was developed as a tool during World War II by the British and Americans to combat the Nazis. Headquartered at the Ministry of Information’s (MOI) top secret facility in Woburn Abbey, Bedfordshire, the Political Warfare Executive (PWE) staff was sworn to secrecy forever, just like the British code breakers in Bletchley Park. This became clear to me, watching the BBC series, The Bletchley Circle (2012) (which features amazing female characters), where former members of the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) refuse to acknowledge their work, even years after the war. It also helped me understand an “incident” I was involved in as a graduate student.

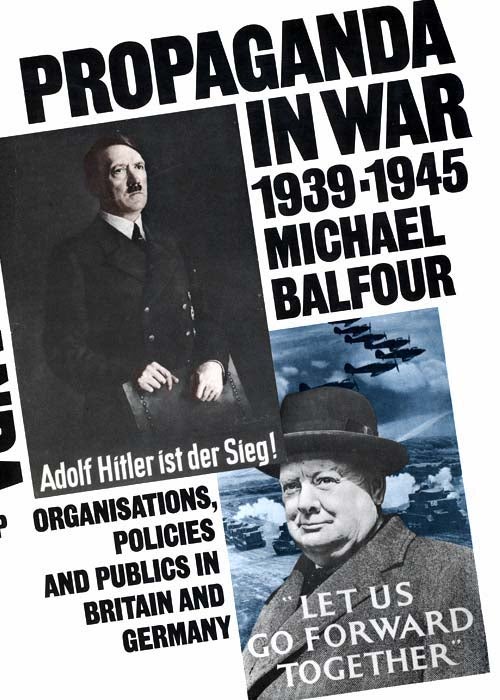

In April 1982, I was privileged to be invited by the late Professor K.R.M. Short to the Rockefeller conference center in Bellagio, Italy, to participate in a symposium, “Film and Radio Propaganda in World War II: A Global Perspective.” At the time, I was writing my dissertation on American anti-Nazi propaganda films, made in Hollywood by German  émigrés, and was the only graduate student among a battery of well-known history professors and former propagandists. I was asked to provide comment for a paper by Erik Barnouw on the black propaganda efforts of Radio Luxembourg, where Barnouw had been a writer. The station was seized by the U.S. Army in September 1944 and transformed into a weapon of psychological warfare, capable with its powerful transmitters of beaming news into all of Nazi Germany. I asked Barnouw whether he knew of similar British efforts to maintain “black” radio stations to propagandize Nazi-occupied Europe. My query led to a strong response by historian Michael Balfour, who seemingly rejected the notion that the British government would act in such an immoral fashion; when governments engaged in black propaganda in time of war, it was best left unsaid.

émigrés, and was the only graduate student among a battery of well-known history professors and former propagandists. I was asked to provide comment for a paper by Erik Barnouw on the black propaganda efforts of Radio Luxembourg, where Barnouw had been a writer. The station was seized by the U.S. Army in September 1944 and transformed into a weapon of psychological warfare, capable with its powerful transmitters of beaming news into all of Nazi Germany. I asked Barnouw whether he knew of similar British efforts to maintain “black” radio stations to propagandize Nazi-occupied Europe. My query led to a strong response by historian Michael Balfour, who seemingly rejected the notion that the British government would act in such an immoral fashion; when governments engaged in black propaganda in time of war, it was best left unsaid.

We of course now know that the British “Political Warfare Executive” used a number of German Jewish exiles, who spoke flawless German, to pretend they were members of a (fictitious) German resistance, broadcasting from a mobile transmitter inside the Nazi Reich, GS1 (Gustav Siegfried Eins). “Der Chef” was supposedly a former Nazi official who knew about Nazi corruption and attacked Hitler and his henchman from the inside. Peter Seckelmann and his cohorts wrote their nightly scripts, utilizing information from German prisoner of war interrogations, actual resistance operatives, and bomber pilot debriefings. The Gestapo apparently went crazy trying to find the fake transmitter, because the broadcast sounded so real. Another fake station, “Soldier’s Radio Calais,” pretended to represent information from the German military. Even American Army Intelligence was utilizing Soldatensender Calais to plan military operations, until the Brits sent a polite note, suggesting they not take the source so seriously, without however fessing up. Michael Balfour had already published his book about his work at PWE, Propaganda in War, 1939-45 (1979), but the conference must have upset him, as mentioned in this obituary.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation