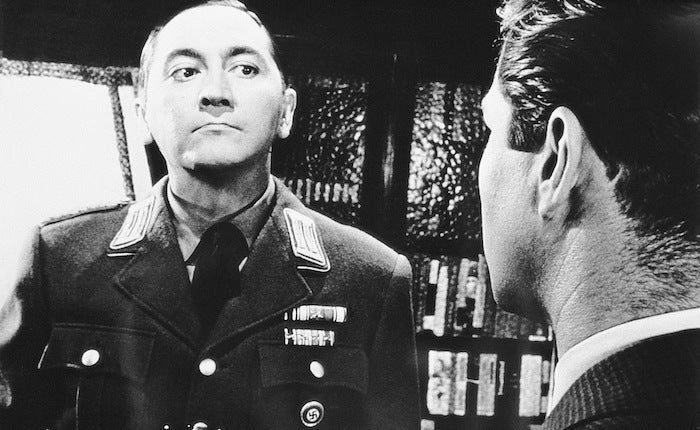

Curd Jürgens (left) in Des Teufels General (1955)

For several decades, post-WWII West German cinema was treated as a mauvais objet by German critics and historians, because the filmmakers of the so-called Oberhausen Manifesto (1962) had proclaimed the death of “Papas Kino” (Papa’s cinema). That generation, out of which New German Cinema evolved, also complained that the German film industry before 1960 was still totally under the control of former Nazis and fellow travelers. It was believed that 1950s German cinema turned out the same tired old genre formulas, just slightly laundered of Fascist content, as they had done since the 1930s. The generation of left-wing film critics coming onto the scene after 1968, therefore, accused the commercial cinema of the Federal Republic of nostalgia, superficiality, sentimentality, escapism and, worst of all, poor production values. What critics demanded was an art cinema, rather than one based on genres and stars. However, a major 2016 retrospective at the Locarno Festival of postwar German cinema, and an accompanying book publication in German and English, edited by Claudia Dillmann and Olaf Möller, offers a historical correction of such prejudices: Beloved and Rejected: Cinema in the Young Federal Republic of Germany from 1949 to 1963 (Deutsches Filminstitut, 2016).

In fact, a historical revision of German cinema between the so-called “rubble films” of the late-1940s and the 1962 Oberhausen Manifesto has been underway in German and Anglo-American academia for more than a decade. Already 30 years ago, Hilmar Hoffmann and Walter Schobert published their anthology, Between Yesterday and Tomorrow: West German Postwar Film, 1946-1962 (Deutsches Filminstitut, 1989). Tim Bergfelder followed suit with the study, International Adventures: German Popular Cinema and European Co-Productions in the 1960s (Berghahn Books, 2004), while monographs by Hester Baer (Berghahn Books, 2009) and Daniela Schulz (Transcript Publishing, 2012) analyzed Heimat films and other genres. More recently, an anthology edited by Bastian Blachut and Imme Klages, Reflections of Damaged Lives? Postwar Cinema in Germany, 1945-1962 (Text+Kritik, 2015) again turned to the subject. The strength of the present volume is its broad view. Consisting of 32 short essays, Beloved and Rejected introduces readers to the landscape of German cinema in the 1950s: animation, documentary, Heimat films, crime dramas, melodramas, remakes, war films, comedies, television films, avant-garde cinema, and somewhat misplaced are essays about the image of Germans in post-WWII Italian and American films. The relatively short contributions are for the most part subjective and impressionistic, focusing on either individual films (Ludwig II, 2012), directors (e.g. Robert Siodmak, Victor Vicas, Frank Wisbar) or general topics, like East-West German co-productions. Just as a young generation of German viewers has discovered these films made by their grandparents, so, too, are most of the authors born well after 1960.

In fact, a historical revision of German cinema between the so-called “rubble films” of the late-1940s and the 1962 Oberhausen Manifesto has been underway in German and Anglo-American academia for more than a decade. Already 30 years ago, Hilmar Hoffmann and Walter Schobert published their anthology, Between Yesterday and Tomorrow: West German Postwar Film, 1946-1962 (Deutsches Filminstitut, 1989). Tim Bergfelder followed suit with the study, International Adventures: German Popular Cinema and European Co-Productions in the 1960s (Berghahn Books, 2004), while monographs by Hester Baer (Berghahn Books, 2009) and Daniela Schulz (Transcript Publishing, 2012) analyzed Heimat films and other genres. More recently, an anthology edited by Bastian Blachut and Imme Klages, Reflections of Damaged Lives? Postwar Cinema in Germany, 1945-1962 (Text+Kritik, 2015) again turned to the subject. The strength of the present volume is its broad view. Consisting of 32 short essays, Beloved and Rejected introduces readers to the landscape of German cinema in the 1950s: animation, documentary, Heimat films, crime dramas, melodramas, remakes, war films, comedies, television films, avant-garde cinema, and somewhat misplaced are essays about the image of Germans in post-WWII Italian and American films. The relatively short contributions are for the most part subjective and impressionistic, focusing on either individual films (Ludwig II, 2012), directors (e.g. Robert Siodmak, Victor Vicas, Frank Wisbar) or general topics, like East-West German co-productions. Just as a young generation of German viewers has discovered these films made by their grandparents, so, too, are most of the authors born well after 1960.

According to their revisionist view, German cinema before mid-1960s was the product of an efficient and well-oiled production machine, which produced films for a mass public. This was a commercially highly successful cinema of genres and stars, like Hollywood, which repeatedly exploited proven formulas. In contrast, those few art films, and films that dealt with the recent Nazi past, often failed to find a public. A quote by a female viewer says it all: “We don’t go to the cinema to see daily life among the ruins, but rather to forget our daily lives in the ruins. For our money, we want the illusions that reality has robbed us of” (p.101). Not only melodramas, but also crime dramas were exceedingly popular, the latter one of the few German genres that had been discouraged during the Third Reich, because there was supposedly no crime under Hitler. Crime films also contributed to the democratic reeducation of the German people, because they visualized a functioning system of justice, wholly absent from 1933 to 1945. Hypersensitive to propaganda, the 1950s audiences otherwise avoided reeducation messages like the plague.

Robert Graf (left) in Wir Wunderkinder (1958)

While the majority of essays offer an inventory of films and trends, film director Dominik Graf contributes a lengthy analysis of the masculine image in postwar German cinema, in which he connects the repressive strategies of his parent’s generation to war trauma. As a director, he is particularly interested in the acting styles of this cinema’s male stars, many of whom had experienced the effects of war on their own bodies, as did Graf’s father, well-known actor Robert Graf. The male stereotype of the loud, aggressive, ideologically pure adventurer, so popular in Nazi cinema, disappeared almost completely after the war, except for Curd Jürgens. That Nazi type was replaced by meditative, physically modest, but professionally competent male heroes, who more often than not supported their leading ladies, rather than abandoning them for war games.

In conclusion, Beloved and Rejected is a very readable and noteworthy introduction to the history of German cinema in the Konrad Adenauer era. At the same time, it throws out as many questions as it asks, making us aware of how much research still needs to be done in this area.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation