Statue of Jefferson Davis

I sometimes go into the community to talk to non-professionals about the film preservation work of the Archive. At one such event, I was approached by a gentleman who seemed genuinely interested in the preservation of history and led off with a statement decrying the recent “destruction of history” through the removal of 100-year-old monuments. I knew he was referring to the obelisks and columns in memory of the Confederacy and Jefferson Davis recently removed in New Orleans. Not wanting to get into an acrimonious discussion, I just responded by telling him about the Archive's efforts to preserve moving images of history, but I kept thinking about the actual question his comment raised. What is history and how do we actually interact with it?

First, it must be said that there is no such thing as a history per se. History, in other words, the chronology of events in the past, the interactions of persons in that past, and the meanings attributed to those actions in the past are unknowable to us today. We cannot travel back in time, as far as I know. “History” is in fact nothing more than an amalgamation of signifiers, which are utilized to construct narratives of history, i.e. stories that give meaning to the past, but also to the present. History is by its very definition an ideological project that morphs from one generation to the next, as those signifiers are continuously reinterpreted in the present.

Thus, the surviving objects of the past, whether films or fashion, novels or newspapers, monuments or museums, have a material reality in the present, but their meanings depend on subjective interpretation. Archives exist to preserve the material culture of the past, allowing every new generation of historians to endow meaning to those objects. As an archivist, I cannot condone “the destruction of history,” but that is not what is happening in New Orleans. According to reports, the monuments will be relocated to an archive, where they can be studied by historians of the reconstruction period of the post-Civil War South, documenting the racism condoned by our society in the past. Preservation, yes; public exhibition, no.

Why not? Simply, because the war monuments to the Confederacy are signifiers of a culture of nostalgia for the pre-Emancipation South. As the Mayor of New Orleans, Mitch Landrieu, noted: “These monuments have stood not as historic or educational markers of our legacy of slavery and segregation, but in celebration of it. To literally put the Confederacy on a pedestal in some of our most prominent public places is not only an inaccurate reflection of our past, it is an affront to our present, and a bad prescription for our future. We should not be afraid to confront and reconcile our past” (CNN).

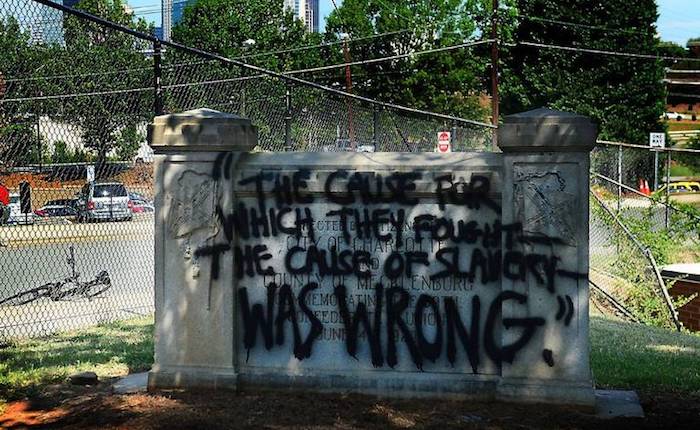

Those who wave Confederate flags and claim that such monuments are about heritage are in fact ascribing meanings to those signifiers, which are no longer acceptable to members of a multicultural, multiethnic society. It is no accident that one of these monuments was not dedicated to the war dead by the survivors, but built in 1911, when the Klu Klux Klan, lynchings and Jim Crow laws were at their most virulent in the South. These monuments at the time of their placement were thus in fact honoring white supremacy, not the blood of the dead. A defaced monument in Charlotte, North Carolina, erected in 1929, memorializes the Confederacy for “preserving the Anglo-Saxon civilization of the South” (Charlotte Observer). One of the other monuments scheduled for removal in New Orleans recalls the “Battle of Liberty Place,” marking a shoot-out during “Reconstruction” between the Crescent City White League and Louisiana State militia over the city's newly instituted biracial police force. Again, an overt monument to white supremacy. Keeping Confederate monuments on public display is thus analogous to the Germans after World War II leaving intact all those monuments to the Führer and Nazism, because in each case such markers cannot be divorced from the cruelty and inhumanity of those institutions.

We cannot deny the past, so Confederate monuments and flags should be archived, preserved and studied, so we never again make such bad choices as a society. However, their role as public displays of history must cease, because our society cannot privilege them as objects of honor when they are also signifiers of slavery in the pre-Civil War South. Now that white supremacists are near the center of power and hate crimes against all minorities have seen a huge uptick, we all need to be more mindful how such symbols of a bygone era are perceived.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation

Comments