Gog (1954)

[Continued from my Mar. 3 blog on the Berlinale]

Science fiction films as a genre are often much more about the present than the future, although most do have prescient moments about a future world. Two films at this year’s Berlinale retrospective, Future Imperfect: Science Fiction Film, struck me as particularly interesting in regards to our present day computerized environment. In GOG (dir. Herbert L. Strock, 1954), a super computer in an American government research facility, deep under the Arizona desert, seemingly controls everything. In Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s two-part television film, Welt am Draht (World on a Wire, 1973), a computer is capable of creating an alternative and parallel reality to our own.

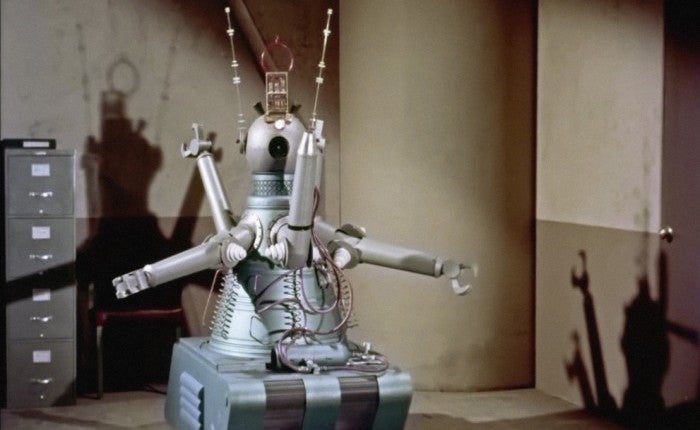

Produced and written by Hungarian émigré Ivan Tors, GOG starred Richard Egan and Constance Dowling (the producer’s wife) with support from Herbert Marshall, John Wengraf, and Philip Van Zandt. The plot: when scientists start dying like flies, due to various freak accidents, Dr. David Sheppard (Egan) is flown to the isolated research facility, where they are working on a future space station. Egan theorizes that some unnamed power (the Russians?) are somehow committing sabotage, but he can’t find any evidence. GOG refers to the two cute robots who help out the scientific team, but then become killers themselves.

Shot in 3-D Naturalvision and wide-screen (1.66:1) on Eastmancolor 35mm negative, GOG was a late entry into the 3-D sweepstakes that had begun more than a year earlier; by the time the film was released in June 1954, the technology was considered “box office poison.” GOG 3-D only ran in seven theatres in Southern California, Phoenix, and Detroit, before its wide release across the country as a flat print. It was later sold to television in black and white and all 3-D prints subsequently went missing. The flat version is available on YouTube.

Gog (1954)

Thanks to the incredible effort of 3-D film preservationist Robert Furmanek, the film was digitally restored last year. Furmanek had acquired the only surviving 35mm left element, a positive composite release print from the United Artists Exchange in New York, which eventually made it into the Packard Humanities Institute Collection at UCLA. It was made available to MGM, which scanned it for preservation purposes. The right eye element from MGM’s preservation inter-positive had been made directly off the original camera negative sometime before the turn of the century and was scanned by Kino Lorber. Furmanek then oversaw the digital clean-up, which included up to seven levels of manipulation: color restoration, left/right panel matching, flicker reduction, image stabilization, detail extraction from the superior right side element, stereoscopic vertical alignment and dirt/damage clean-up.

Apart from the fact that the film’s color and 3-D rendering looked great in Berlin, I was fascinated by the premise that everything in the research facility from doors to robots to food preparation was managed by the computer, NOVAC; a fantastic fact then, and a reality nowadays. The computer in fact turns out to be the killer, apparently because it has been hacked by the Russians (unnamed) who are flying a spy plane overhead and somehow communicating with NOVAC. Once the plane is shot down, the computer returns to normal. The New York Times called the film “utter nonsense,” but today it is more than plausible, given recent Russian interference in our electoral process.

World on a Wire (1973)

Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s two-part World on a Wire was first screened on German television in October 1973, running 205 minutes. Shot in real locations in Munich, Cologne and Paris, the film was based on Daniel F. Galouye’s 1964 science fiction novel, Simulacron-3. The digital restoration from 16mm reversal was screened in Berlin in 2010, but reprised for this retrospective; a Blu-ray was released by Criterion in 2012.

The story concerns the Institute for Cybernetics and Futurology, which is operating a super computer, “Simulacron,” that can predict the future by simulating real world conditions through the creation of tens of thousands of “identity units,” who also believe themselves to be real. After the computer’s inventor dies mysteriously, Dr. Fred Stiller is brought in to find the computer glitches, only to discover that his head of security may have been a “memory unit” who escaped to the real world. Worse, Stiller discovers he may also be a simulation. Teasing out the real from the virtual becomes an almost impossible task, due to the limits of human subjectivity. We are in the Matrix.

World on a Wire (1973)

Fassbinder’s camera and decor clearly support such a reading. The Cybernetic Institute is all glass walls, sterile plastic furniture, neon lighting and mirrors. Influenced by his discovery of Douglas Sirk’s melodramas in 1970, Fassbinder consistently captures the protagonists and their mirror images in the same frame, their bodies often remaining static and staring straight into the camera. Furthermore, the stylized acting by Fassbinder’s large stock company is typical for Fassbinder in this period, but here it leaves the impression of mass somnambulism, as if humans are waiting for the computer to activate them. The Simulacron room is a veritable house of mirrors. Time and again we think we are seeing a person talking, when in fact it is their mirror image. Unlike American sci-fi based on action, Fassbinder’s vision of the future is based on stasis, on defining the real through alternative facts, until the real is no longer visible. This could potentially also be a political strategy.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation