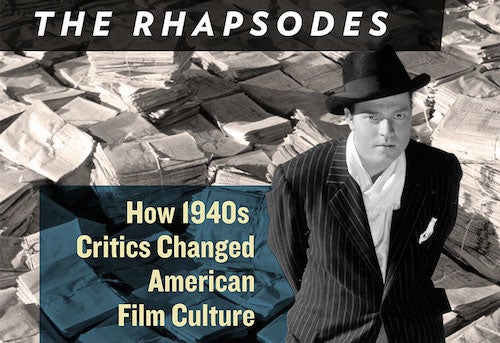

David Bordwell’s monograph, The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture (University of Chicago Press, 2016) has been sitting on my “to read” pile for months, but I finally got a chance to break the spine over the winter break. In this slim volume, Bordwell discusses the film criticism of Otis Ferguson, James Agee, Manny Farber, and Parker Tyler, all of whom he identifies as the first American mainstream critics/journalists to take film seriously as a mass medium, and not just a pleasant diversion for the masses. Many if not all of these names are probably unfamiliar to younger readers, because the culture of film criticism has all but disappeared in our internet era of every man/woman his own critic; most “critics” now seem to be more or less advertisers for new films. It wasn’t always so.

When I first got interested in cinema in the 1970s, it was my goal to become a film critic for a major magazine or newspaper, because I thought critics were really cool. There was my hero, Andrew Sarris, at the Village Voice (where Jonas Mekas also wrote about avant-garde film), Pauline Kael at the New Yorker, John Simon at New York magazine, Jay Cocks at Time, Stanley Kauffmann at New Republic, etc. Around the same time, publishers were falling over themselves to publish collections of reviews by Dwight MacDonald, Renata Adler, Judith Crist, and others, as well as all the critics named above by Bordwell. Rhapsodes refers of course to ancient Greek performers of epic poetry, but Bordwell uses term to identify critics who analyzed rather than simply reviewed films, and did it with style. Bordwell states in a blog that he “admired the daring, ecstatic, sometimes zany quality of their writing. Like the ancient singers of tales, these critics seemed in touch with the gods – in this case, the gods of cinema.”

Agee et al., in particular, were strongly influenced by New Criticism, which meant that they privileged “close readings” of films and literature, based on evidence in the work, rather than preconceived ideologies, as was the habit of contemporary leftist film critics. Like David Bordwell and many other film studies academics who came out of English Departments (before films studies existed), I, too, had grown up in an English Department, dominated by the New Criticism of I. A. Richards, so David’s The Rhapsodes reminded me how exciting that period of discovery was for me.

Bordwell begins by reminding us of the golden age of film criticism from the 1940s through the 1980s, when a vibrant cinema culture (European art cinema, underground, Hollywood revivals) supported serious film criticism of all kinds in the popular and academic press. Art and revival houses blossomed and everyone was writing about this relatively new art medium. Violent controversies between highbrow critics (Hollywood is trash!) and lowbrows (film is not art but entertainment), between auteurists (the director is the film’s author) and anti-auteurists (film is a communal project), between supporters of narrative and those of the avant-garde, became topics for discussion around the water cooler. In the following, Bordwell devotes a chapter to each of his four rhapsodes.

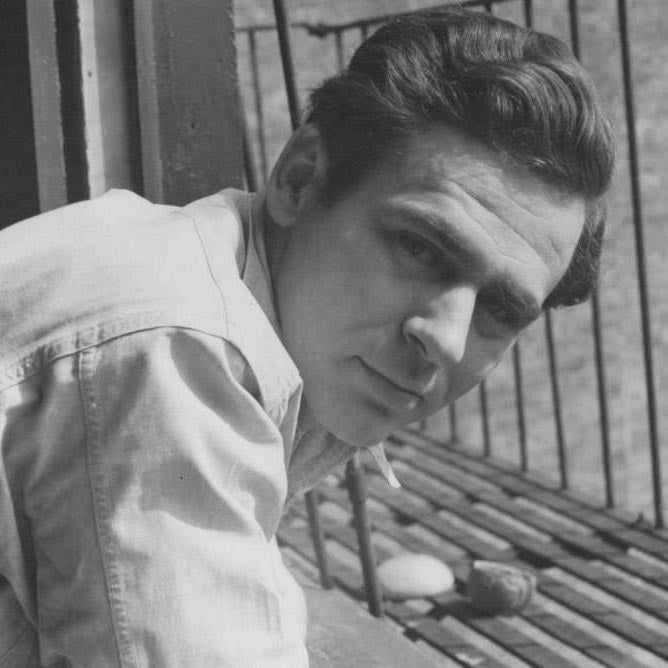

Taking Hollywood films seriously, Otis Ferguson championed naturalistic storytelling, based on continuity editing and scenes of action rather than dialogue, in other words the kind of film Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristen Thompson would later identify as the classical Hollywood style. He also preferred the unobtrusive camerawork of a William Wyler to the stylistic flourishes of an Orson Welles. “Ferguson wanted insights; Agee demands epiphanies.” Writes Bordwell (p. 69). James Agee, probably the first film critic to become a household name, was a romantic who expected films to achieve not only realism, but also emotional depth through symbolism, the way poetry could. Agee’s criticism also wanted to convey the difficulty of interpretation, often vacillating in his response to a film within a single review.

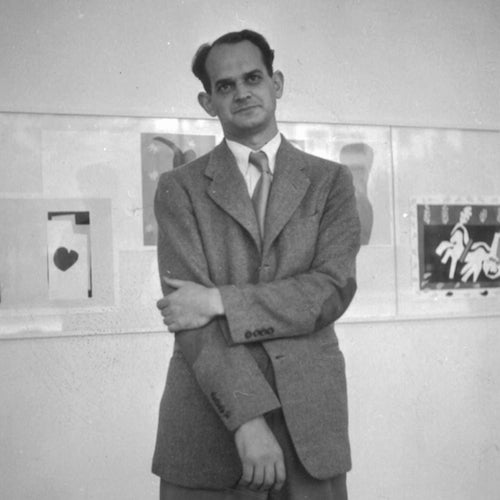

Manny Farber started as an art critic, and believed in modernism in art, but films were for him “illustrations” that could communicate visually, like no other medium. Like Ferguson, Farber accepted a degree of naturalism, but also privileged the kind of stylistic necessities that B film directors had to implement and thus became an early champion of film noir. Focusing on the composition within the film frame, Farber defined “negative space” as the relationship in space of objects to one another within the film frame, advocating for economy of style and narrative finesse in all kinds of popular media. His published collection of reviews, Negative Space (1971), refers both to this sensitivity to what the French call mise-en-scène, and to the critical stature, i.e. lowbrow, of many of the films he considers worthy of criticism.

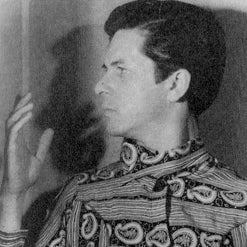

Bordwell admits that Parker Tyler fits less neatly into the new critical category, but he loves his wacky prose. He did not publish his criticism in magazines, but already collected in book form. He was also not a realist, but a Freudian surrealist who championed the avant-garde and the outré. Freud and Jung (for his mythology) are Tyler’s spiritual fathers, not John Crowe Ransom. He makes it into Bordwell’s pantheon because of his extravagant writing style, which could hold its own against any of the others mentioned above in its defiance of standard grammar. This chapter may have benefited from a bit more attention to Parker Tyler’s queer aesthetics, formulated decades before Stonewall.

Ultimately, then, Bordwell seems to love these critics more for their use of language and style than for their actual critical insights into often long-forgotten films. And indeed, there is pleasure in reading great writers express their thoughts on films that are familiar, simply because really good prose is always hard to find.

Photos, right: James Agee, Manny Farber, Parker Tyler.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation