King of Jazz (1930)

This summer, I attended a sold-out screening of Universal Studios’ digital restoration of King of Jazz (1930) at the Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna. For decades the film had a somewhat underwhelming reputation as “Universal's Rhapsody in the Red,” because it was one of the studio’s biggest money losers, contributing ultimately to the demise of the Carl Laemmle era. Because of its box office failure, the film was rereleased in 1933 in a reedited version that was 30 minutes shorter than the original 105 minute cut; for decades the complete version was thought to be lost. In fact, a British collector, Philip Jenkinson, had tried to piece together a longer version in the 1970s, which was significantly longer at 93 minutes, but also included material added to the 1933 reissue. That version played at the New York Film Festival in September 1970, while Jenkinson sold (illegally) 16mm prints of his compilation to his collector friends. By the end of the century, though, the only video version available was a poor quality VHS tape from the 16mm compilation. Once it was named to the National Film Registry in 2013, Universal decided it was time to attempt a restoration.

Completely shot in two-color Technicolor, King of Jazz was released in April 1930, more than a year and a half after Paul Whiteman had been signed to make the film. It was a troubled production for a number of reasons. First, the film was assigned to Wesley Ruggles and Paul Fejos, before Universal hired novice theater director John Murray Anderson at Whiteman’s insistence at an inflated salary of $2,500 per week. Secondly, within months, the production got the reputation of being “the famous Paul Whiteman film without a story.” Indeed, after spending more than a year coming up with a plausible plot, Anderson tossed the story in favor of a series of theatrical sketches. Thirdly, Universal was having serious cash flow problems, because of disappointing sales on its previous slate of films, while continuing its financial commitment to this movie and to All Quiet on the Western Front (dir. Lewis Milestone, 1930), both very expensive productions. Unfortunately, by the time the film opened, audiences had tired of stage musicals, popularized by The Broadway Melody (dir. Harry Beaumont, 1929). As a result, the film lost more than $1.2 million on an investment of $3.019 million, in contrast to All Quiet, which cost $100k more, but earned almost $4.1 million.

The restoration of the general release version of 1930 was extremely complicated and expensive. Former preservationist Bob O’Neil had done tests for an analog restoration in 2011 at YCM Laboratories, but an analog restoration at $250k+ was more than Universal could afford, so the project was put on hold. After its placement on the Registry, though, Universal executives approved a digital restoration in early 2015. First, Universal used their original two-strip camera negative of the 1933 reissue, which they had kept in their vaults. That the negative still existed in any form is actually amazing, given that only 15% of all two-color features survived at all. That negative was scanned at 4K on an Oxberry Cinescan at Cineric Labs in New York. More importantly, a surviving nitrate print from 1930 with a length of 83 minutes had been found in the Raymond Rohauer Collection, which was scanned at 4K by Prasad Corp. on a Scanity, because the print’s 1.8% shrinkage demanded sprocketless scanning. Although no shooting or continuity script survived – usually used to figure out the exact continuity of shots – Universal had a surviving track negative of the 104 minute version, so that images could be matched to sound. Two other incomplete prints from UCLA and the Danish Film Institute were used to fill larger holes, but then there was still footage missing (sometimes only a few frames, sometimes as long as 63 frames), that could not be found. In those cases, the Universal restoration team under Peter Schade decided to interpolate stills or shots from other parts of the film, so that no gap in the music appeared. Combining all of the various scanned elements into a uniformly looking whole was the job of the digital restorationists at Universal who removed scratches, stabilized the image, and color corrected the visuals. Meanwhile, the original track was digitized and cleaned up, with only a few sound bites from the 1933 version.

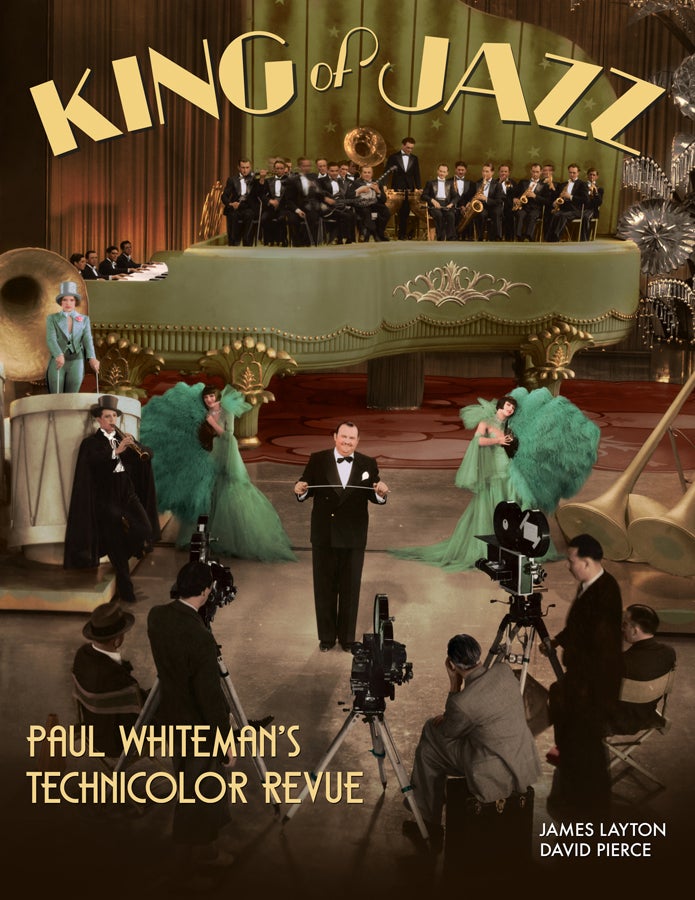

Accompanying the new restoration, James Layton and David Pierce have produced a magnificently illustrated volume, King of Jazz: Paul Whiteman’s Technicolor Revue, edited by Richard Koszarski, which tells all you will ever want to know about this film. Handsomely illustrated with much rare material, the authors discuss the rise of bandleader Paul Whiteman, the history of the Broadway revue, the film’s production, a scene-by-scene description, the creation of foreign versions, the restoration process, and an appendix chocked full of further information. This is a real treasure for collectors.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation