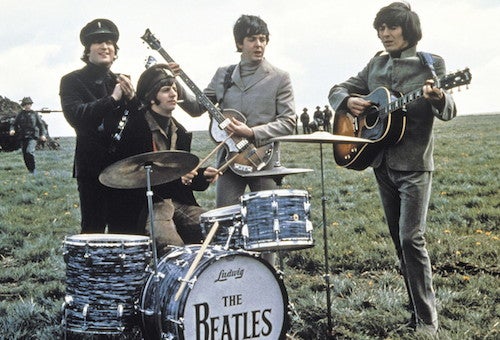

Help! (1965)

Ron Howard’s feel-good documentary film about The Beatles’ rise to fame has been in theaters for a number of weeks, receiving wide critical acclaim and steady-holding audiences, as word of mouth gets out. And why not? If no one else goes to see the film, my baby boomer generation was sure to be front and center, I assumed. So, I went to see the film last week at my local Laemmle, and was not disappointed, in either the audience or the film (more on that later). Except for one young couple, the Saturday night audience was 100% boomer. My wife and I arrived early and watched as one couple after another, in their late 50s or older, took their seats. It was an oddly sobering experience.

I don’t think anyone who came after The Beatles can ever really understand what the group meant to kids who grew up with them. Sure, The Beatles helped turn popular music into a cultural phenomenon that propelled society from the conservative ‘50s into the swinging ‘60s, exploding norms of style, cultural hierarchies, and often families. Every one of us has their own stories about The Beatles, each of them different yet also very much the same. Each of us can trace that part of our lives on Beatle time; our common bond.

My introduction to The Beatles came when a girl I liked in my seventh grade class at my suburban Chicago junior high told me I looked like John Lennon and proceeded to show me John’s silhouetted image on the “Meet the Beatles” LP she was carrying. A few weeks later I saw the Ed Sullivan broadcast of February 1964, and watched as my parents and their generation howled in derision. The generational fronts were thus drawn. The Beatles were our secret, our common bond against our parents, and an immediate form of mutual identification and cultural currency. It allowed kids who were total strangers to form immediate bonds. Once, after my parents had moved the family to Germany, we had to spend time with the children of one of my dad’s business associates; we instantly bonded, when they played their newly acquired LP, Rubber Soul. In fact, the very act of listening to The Beatles together on a stereo became a cultural practice of the boomer generation that seemingly disappeared with the advent of the Walkman.

My introduction to The Beatles came when a girl I liked in my seventh grade class at my suburban Chicago junior high told me I looked like John Lennon and proceeded to show me John’s silhouetted image on the “Meet the Beatles” LP she was carrying. A few weeks later I saw the Ed Sullivan broadcast of February 1964, and watched as my parents and their generation howled in derision. The generational fronts were thus drawn. The Beatles were our secret, our common bond against our parents, and an immediate form of mutual identification and cultural currency. It allowed kids who were total strangers to form immediate bonds. Once, after my parents had moved the family to Germany, we had to spend time with the children of one of my dad’s business associates; we instantly bonded, when they played their newly acquired LP, Rubber Soul. In fact, the very act of listening to The Beatles together on a stereo became a cultural practice of the boomer generation that seemingly disappeared with the advent of the Walkman.

For us, Beatles music was always about the music, from the early screamers to the tender and melodic love songs that both John and Paul composed with amazing speed. My twin brother, Michael (another Beatles fan) and I saw Help! i.e. Hi-Hi-Hilfe! (dir. Richard Lester, 1965) in a suburban cinema in Essen, although I can’t remember whether the film was dubbed or not. Many critics mark the transition to mature Beatles with Revolver, but for me their music reached a whole new level with Rubber Soul, because the lyrics and music achieved an unprecedented complexity and ambiguity. When The Beatles broadcast the premiere of “All You Need Is Love” in June 1967, I was glued to the television, along with everyone else I knew. A worldwide television audience for one event was itself almost unconceivable; it was the moment the world became wired. When I was courting my wife in the 1980s, I gave her new copies of all the Beatles LPs, because her discs had been played to death.

Television broadcast of "All You Need is Love," 1967.

When The Beatles split became a reality in 1970, most people I knew went into a kind of shock. The whole “Paul is Dead,” hysteria, when virtually every college kid in the country was running parts of “Revolution No. 9” on The White Album backwards, frantically looking for clues, was a ritualistic coming to terms with the breakup. While Yoko Ono became for almost everyone a scapegoat you loved to hate for causing the break-up, I moved on. After The Beatles, I continued to identify with my working class hero, Lennon, during his solo career and purchased every new album, sporadic as they were in the 1970s. When Mark David Chapman killed Lennon, I experienced a deep sense of mourning for the first time in my life.

To be continued...

Trailer for The Beatles: Eight Days a Week:

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation