Expressionism and Film (John Libbey Publishing, 2016)

Just as Hugo Münsterberg’s The Photoplay constituted one of the first published works of film theory, so too was Rudolf Kurtz’s Expressionismus und Film one of the first, if not the first, art historical treatises to examine film as an equal of the other arts. Published in 1926 in Berlin by the cinema trade magazine, Die Lichtbildbühne, the volume became a German-language classic, at least until the Nazis banned the work in 1933, because it was deemed to be degenerate art. It was not reprinted until 1965, when Swiss publisher Verlag Hans Rohr released a facsimile. It has been repeatedly quoted in German film studies, although it has not been as influential as Lotte Eisner’s post-WWII art historical analysis, The Haunted Screen: Expressionism in the German Cinema. The book was translated into French and Italian in the 1980s, but now for the first time, Kurtz’s Expressionism and Film (John Libbey Publishing, 2016) is available in an excellent English translation by Brenda Benthien, edited with an afterword by Christian Kiening and Ulrich Johannes Beil.

Born in Berlin in 1884, Rudolf Kurtz was in fact a contemporary supporter of German Expressionism, publishing numerous essays, reviews and commentaries between 1910 and 1914, as well as a foreword to the German edition of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s Manifesto of Futurism. By 1916 he had become involved in the film industry, working for 10 years as a dramaturge for the Projektions “Union” AG, where Ernst Lubitsch got his start and which would be absorbed by the Universum Film AG (UFA) in late-1917. He then became the editor in chief of Die Lichtbildbühne, which was founded in 1908 by Karl Wolffsohn as a weekly trade journal.

Kurtz begins by noting that there is no precise definition of Expressionism, that initially it was a reaction to Impressionism, but also a “world view” that is anti-psychological. As a historical movement (by 1926, Expressionism’s influence had waned in all the arts, including film), Kurtz sees it as “the hallmark of a particular generation” (p. 9). He then compares literature, fine art, architecture, music, the stage and applied art (typography), before focusing on expressionist cinema and isolating set design, the camera and lighting as elements most conducive to expressionist treatment.

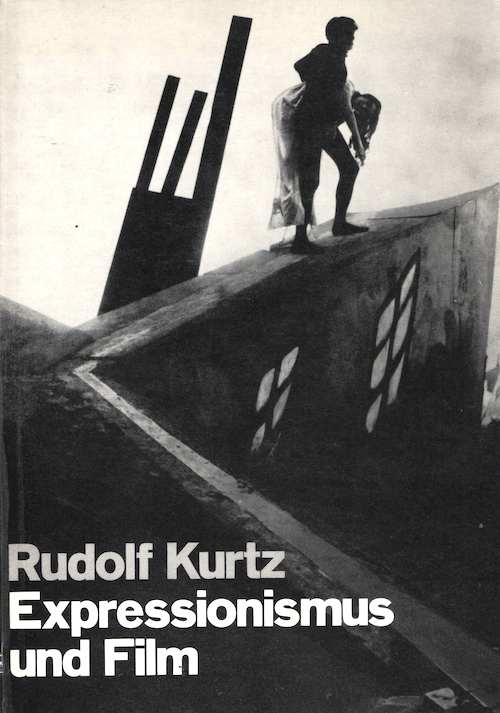

Unlike Eisner’s book, whose reception in film studies has led to a conflation of Expressionism and German silent cinema in general, Kurtz limits his discussion of expressionist cinema to only six titles, whose expressionist qualities are defined mostly through set design and acting, noting that film seized on Expressionism’s decorative qualities: The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (dir. Robert Wiene, 1919), From Morn to Midnight (dir. Karl Heinz Martin, 1920), Genuine (dir. Robert Wiene, 1920), The House on the Moon (dir. Karl Heinz Martin, 1921), Raskolnikow (dir. Robert Wiene, 1923) and Waxworks (dir. Paul Leni, 1924). He treats a number of these films as artistic failures, especially Martin’s The House on the Moon, which he considers overstuffed with effects and too many plot devices for their own sake.

Kurtz then goes on to explain that other German films have incorporated stylized elements of Expressionism, especially Ernst Lubitsch’s The Wildcat (1921), Nosferatu (dir. F.W. Murnau, 1922), Die Nibelungen: Siegfried (dir. Fritz Lang, 1924), The Golem (dir. Paul Wegener, 1920), Backstairs (dir. Leopold Jessner, 1921), and The Street (dir. Karl Grune, 1923). In a later chapter, Kurtz then defines expressionist style as tied to script, direction, acting and set design.

Finally, Kurtz devotes a chapter to “abstract art,” specifically the abstract films of Viking Eggeling, Walter Ruttmann, Hans Richter, Fernand Léger and Francis Picabia, which he likewise defines as anti-psychological: “What was rejected in principle was the psychological experience, the dominance of feeling. In its place stepped construction from out of conscious, metaphysically-determined Will” (p. 89). As elsewhere in this new edition, this chapter is heavily illustrated with abstract art and film examples, since the original 1926 edition was in fact a large format art book.

From Morn to Midnight (1920)

Finally, as the editors have noted in their long and informative afterword, Kurtz’s text is itself expressionist: “Whenever Kurtz describes a film’s content and sequence, expressionist prose blazes the way, characterized by ellipses and oxymorons, staccato sounds and the pathos of existence” (p. 155). The editors also present Expressionism and Film in a historical context, noting the ways Lotte Eisner in particular took her lead from Kurtz. For English readers interested in silent German cinema, there are many discoveries to be made here.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation