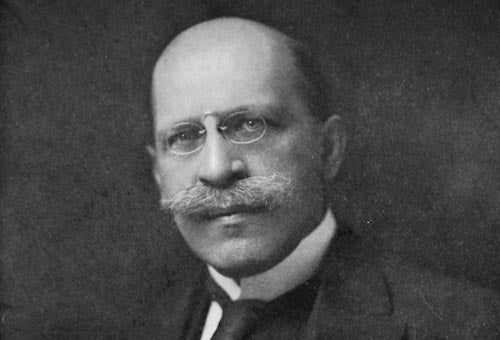

Hugo Münsterberg

At the beginning of July, I gave the third keynote speech at “A Hundred Years of Film Theory. Münsterberg and Beyond: Concepts, Applications, Perspectives,” an international conference in Leipzig dedicated to the memory of Hugo Münsterberg, whose The Photoplay: A Psychological Study (1916) is considered one of the first, but not the first book – that honor goes to Vachel Lindsay’s The Art of the Moving Picture (1915) – on film theory. Münsterberg, who had been invited to Harvard by William James in 1890 to establish a psychological laboratory there, had made a name for himself in America, not only as the one of the most famous academic psychologists in the country, but also as a popularizer of applied psychology, publishing dozens of studies that looked at everyday life. When Münsterberg collapsed and died at his Radcliffe lectern in December 1916 at the age of 53, it was generally agreed he had expired from the stress of vilification, having taken a pro-German stance in World War I. My own talk dealt with the historical irony that the hated “Hun” was born a Jew, who could not get an academic position in the Second Reich, due to anti-Semitism.

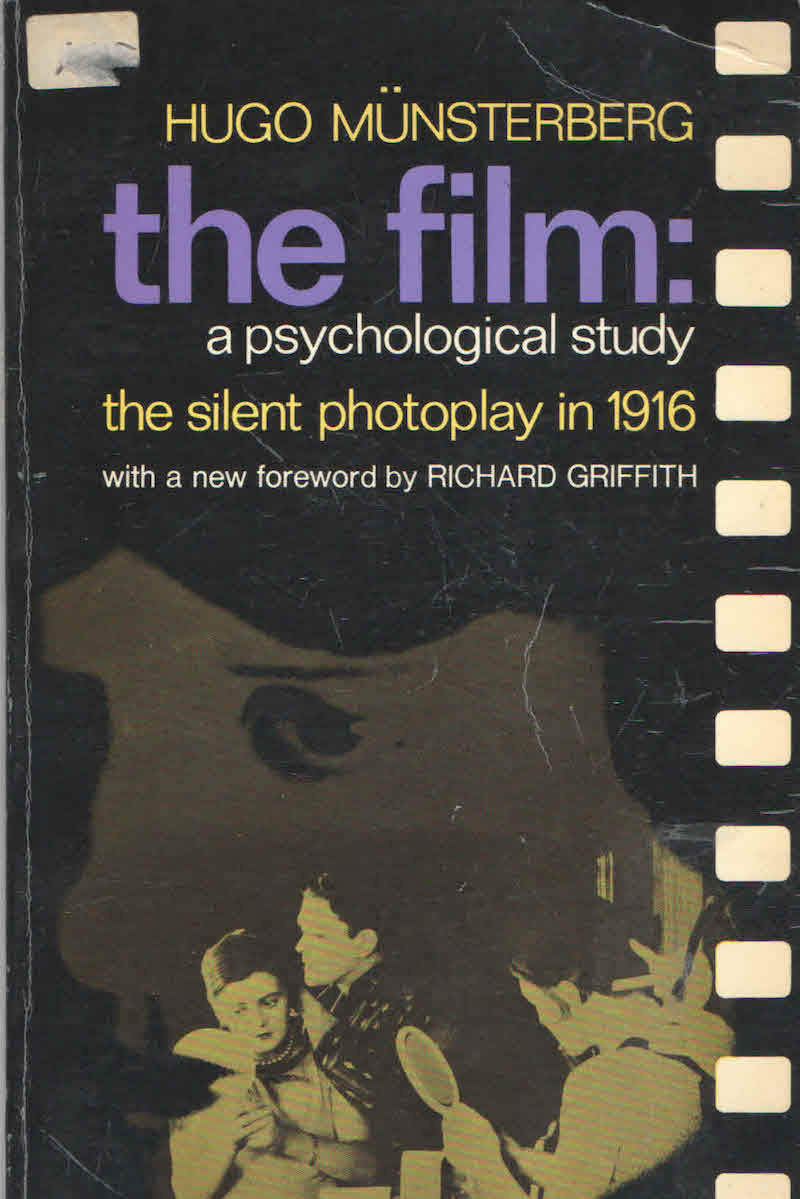

Organized by Rüdiger Steinmetz, chair of the Communications Department at the University of Leipzig, the conference had opened two days earlier with a keynote by Ian Jarvie (Toronto). He contextualized Münsterberg in terms of a philosophy of film, noting that The Photoplay had been completely forgotten for five decades, before its republication in 1970 at the dawn of film studies as an academic field. It has remained in print ever since. However, while commenting on Münsterberg’s achievement as a precursor of cognitive psychology and film theory—Münsterberg was the first to point out the difference between the screen’s two dimensions and our perception of a third dimension—Jarvie also criticized the philosopher’s at times impenetrable Kantian idealism in such works as The Eternal Values (1909). Taking a somewhat contrary view in a second keynote the next morning, Jörg Schweinitz (Zürich) argued that Münsterberg’s idealism had been misunderstood, because of the bad translation of Eternal Values, which had originally been published in German as Philosophie der Werte, and formed the basis for The Photoplay’s aesthetics. In particular, a key aesthetic concept, “die Aufhebung der Wirklichkeit” had been mistranslated as “aesthetic of isolation,” giving it a Neo-Kantian idealist interpretation, when it should have been translated as “the preservation/abolition/transcendence of reality,” implying a much richer dialectical, Hegelian reading. Schweinitz also noted that Rudolf Arnheim, who literally founded cognitive film theory, stated in the 1980s that he probably would not have written his famous Film as Art, if he had had access to Münsterberg.

The first day had also seen Steinmetz discuss Münsterberg’s ambiguous public role between Germany and the United States which vacillated between self-appointed bridge builder and alleged spy for the Kaiser, the historical truth being he was probably only a private propagandist rather than a paid agent for the Kaiser. David Culbert (Baton Rouge) continued that line of inquiry, teasing out Münsterberg’s close relationship to George Sylvester Viereck’s pro-German New York weekly, The Fatherland, which cost the Harvard don his friendship to Wilson, Roosevelt, and most of the Harvard elite, including Harvard President Charles William Eliot.

During the rest of the four-day event, the conference split into simultaneous panels with speakers focusing in 20-minute talks on Münsterberg, while others addressed aligned topics. Thus, Steve Choe (San Francisco), Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann (Jerusalem), Emilie Langer (Leipzig), Katrin Döveling (Leipzig), Annabel J. Cohen (Prince Edward Island), and Matthias Wittmann (Basel) discussed further aspects of Münsterberg’s life and work, while others, like Paulina Kwiatkowska (Warsaw), Tobias Hochscherf (Flensburg), Florian Mundhenke (Leipzig), Vebhuti Duggal (New Delhi), Thunnis van Oorth (Middelburg), Anna Luise Kiss (Potsdam-Babelsberg), Victor Zatsepin (Moscow), Daniel Wiegand (Stockholm), Michael Punt (Plymouth), Fernando Ramos (Leipzig/Madrid), Marko Rojnic (Kent/Zagreb), and Mario Slugan (Chicago) presented a host of film topics in honor of Münsterberg’s legacy.

Hugo Münsterberg with his students in Freiburg, c. 1891 (source).

Two papers of particular interest to me were by Charlotte A. Lerg (Munich/Washington, D.C.) and Jeremy Blatter (New York). Lerg—I last saw her in the arms of her father, Winfried B. Lerg, my doctoral thesis advisor in Münster—talked about Münsterberg’s advocacy for Harvard at a time when America’s elite universities, including Harvard, Columbia and Chicago began intense public relations campaigns for alumni dollars. Münsterberg apparently often leaked information to the press, which was tolerated until the professor’s pro-German positions began to be an embarrassment; after that Harvard’s A. Laurence Lowell still supported him publicly in the interest of academic freedom, but became increasingly annoyed privately. Blatter, whose dissertation on Münsterberg’s applied psychology research was the talk of the conference, pointed out to what degree the Harvard professor had become a household name in the pre-WWI years. He was the subject of literally hundreds of articles, as he tackled such everyday problems through applied psychology as witness behavior, industrial efficiency, psychotherapy, art education, even street lighting in the city.

I’m told a volume of conference proceedings is in the works.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation