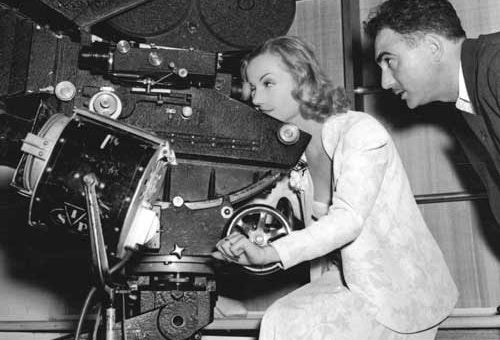

Carole Lombard

Back in April I attended the opening of our film series, Independent Stardom on Screen, co-curated by Chapman University film studies professor Emily Carman, who wrote her UCLA dissertation on the subject which has now been turned into the book Independent Stardom: Freelance Women in the Hollywood Studio System (University of Texas Press, 2016). At a pre-screening book signing, Emily, who is also a former student of mine, autographed my copy, which I’ve finally gotten around to reading.

Emily Carman revises the standard narrative of the Hollywood studio era, which perceives the near monopoly of film production, distribution and exhibition as a capitalist system that enforced long-term labor contracts to maintain control over their labor force. Actors in particular were thought to be exploited, while the male patriarchy of film producers added gender and sexual exploitation to the mix with their actresses; as elsewhere in studio era Hollywood, women were denied any agency at all. Not until the landmark Olivia de Havilland lawsuit of 1943 against Warner Bros. and Lew Wasserman’s deal for James Stewart for Winchester ’73 (1950) were actors considered able to take control of their careers and income potential through free agency.

However, according to Carman, this narrative ignores the experiences of a certain group of female stars who opted out of their studio contracts to pursue freelance careers as actor-producers as early as the 1930s. In Independent Stardom, the author traces the careers of Janet Gaynor, Miriam Hopkins, Carole Lombard, Constance Bennett, Irene Dunne and Barbara Stanwyck, and their more or less successful attempts to forge freelance film acting careers that gave them the freedom to negotiate not only what films they made (compared to actresses under long-term contracts who were subject to fines, if they turned down roles) and how much they got paid for their work, while again studio contracts limited pay increases. Engaging with previously untapped resources, such as actor’s contracts, Emily Carman has indeed rewritten the standard narrative.

Barbara Stanwyck

Carman begins by exploring the relationship between these Hollywood actresses and their agents, who could forcefully argue for their client’s interest against the intractable positions of most studio bosses. The popularity and box office muscle of someone like Irene Dunne allowed her agent, Charles Feldman, to mobilize her perceived economic power, negotiating loan-outs and off-casting, and allowing actresses to play more challenging roles. Stanwyck and Bennett, in particular, quickly opted out of studio contracts to go freelance, giving them control over their star persona and salary. In 1942, Stanwyck was the highest paid woman in the nation, “as reported by the US Treasury” (p. 43). Freelancing also allowed someone like Constance Bennett to negotiate a percentage deal from the studio’s distribution income, whereby her salary was tied to box office performance. If the film did well, she would earn well, but it also meant her earnings were taxed as capital gains (25%), rather than as personal income – at that time, a whopping 75% for higher incomes. The move could, however, backfire, as in the case of Clara Bow, who earned nothing when her comeback films failed to perform. Given studio accounting practices, Miriam Hopkins did well to insist on her accountant’s access to studio books.

However, even actresses under studio contract, like Ann Harding, Katharine Hepburn and Claudette Colbert, had the power to negotiate outside deals with other studios, percentage deals for individual films, or more creative freedom. Colbert was the most successful in this vein, receiving both a very lucrative longterm contract with Paramount after the success of It Happened One Night (1934), as well as deals with Warner Bros., Columbia and Universal, which gave her approval over directors. Furthermore, her $100,000 per film salary was augmented by a 10% percentage deal, making her one of the highest paid actresses in Hollywood by the end of the 1930s. On the other end of the spectrum, however, were women of color, like Anna May Wong and Lupe Vélez, who despite starring roles never received studio contracts, were forced to freelance at low wages, and were cast exclusively in stereotyped ethnic supporting roles; they were also subject to censorship, because of the MPAA’s prohibition on miscegenation.

Ida Lupino

Independent stardom also allowed the actresses discussed here to control their own publicity, i.e. their star persona. The numerous fan magazines promoted all stars, but, given their mostly female readership, were especially interested in the careers of Hollywood’s top-tiered actresses, their family lives, relationships and business acumen. For example, Barbara Stanwyck’s humble beginnings as Brooklyn-born Ruby Stevens and her subsequent independence as a savvy businesswoman received intense positive scrutiny in the fan press. Bennett and Hopkins, on the other hand, were not willing to cater to publicity and were therefore discussed in more negative terms as pampered and overpaid stars. Carole Lombard was the most successful “publicity hound,” forging an image of a hard-working, independent woman and admired star.

Emily Carman concludes that it was these actresses in the 1930s that paved the way for the next generation of Hollywood women, who would become their own producers and/or directors, like Ida Lupino. At the same time, she notes that fortunes shifted for top female stars after World War II, once scientific audience research revealed that 1930s female audiences had given way to more male and youth-oriented audiences.

This book is a must read for anyone interested in Hollywood’s studio era.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation