With all the press buzz around Quentin Tarantino’s 70mm western epic, The Hateful Eight (2015), I really wanted to make sure I saw the film as a film, and not just as a digital cinema package (DCP). The opportunity arose when the film opened the Museum of Modern Art’s The Contenders film series at the Hammer Museum earlier this month. After briefly attending MoMA’s opening night reception at Mr. Chow’s in Beverly Hills, I rushed to the Hammer, realizing in the process that the reception was not for people attending the screening. At the Hammer I was greeted by a full house, so I went to the projection booth to check on Jim Smith and Amos Rothbaum, UCLA Film & Television Archive’s projectionists, who were mounting the five huge 70mm reels onto our 35/70mm Kineton projectors. I wanted to make sure we were not subject yet for another blog about a failed screening. Working with Panavision, the Hammer had temporarily installed Panavision Steinheil Pan-Quinon 70, 114mm lenses, in order to screen the print, given the Billy Wilder Theater’s short throw. Happily, UCLA’s projectionists came through and the screening proceeded without a single hitch.

As is well known, Quentin Tarantino convinced the Weinstein Company to finance the installation of 70mm film projectors in 96 theaters for his “roadshow” presentation of The Hateful Eight at a cost of $60 - 80,000 per screen, including hiring special projectionists. The film opened Christmas day and went into wide release in January 2016 in 35mm film and DCP iterations, the wide release missing some six minutes of roadshow footage, but including an overture and intermission. No film in recent memory has experienced such a wide release on analog film: Christopher Nolan’s 70mm science fiction epic, Interstellar (2014), for example, only opened on 11 screens. Surprisingly, the film broke theater records for its first roadshow week and has earned over $33 million in its first week of wide release.

The Hateful Eight was shot in Ultra Panavision 70mm, a widescreen format developed in 1957 by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and Panavision to compete with 20th Century-Fox’s CinemaScope and Paramount’s VistaVision. Working with the Mitchell Camera Company to modify the 65mm Mitchell camera’s manufactured for MGM’S failed “Reallife” 65mm system (1930), Panavision created a 70mm system that was similar to Todd-AO’s widescreen process, except that the film was shot at 24 instead of 30 frames per second and the lenses were anamorphic, rather than spherical. With an aspect ratio of 2.76:1, Ultra Panavision was wider than any other film format – most films today are projected at either 1.85:1 or anamorphically at 2.35:1. While Raintree Country (1957) was the first film shot with the new camera and lenses, the first film released in 70mm was Ben Hur (1959). Only seven other films were ever shot in Ultra Panavison 70, before Tarantino’s work: Mutiny on the Bounty (1962), It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963), The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964), The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965), The Hallelujah Trail (1965), The Battle of the Bulge (1965), and Khartoum (1966). For 48 years, no one had used Panavision’s Ultra 70 lenses, until Quentin came knocking, making Hateful Eight only the 10th film shot in the process.

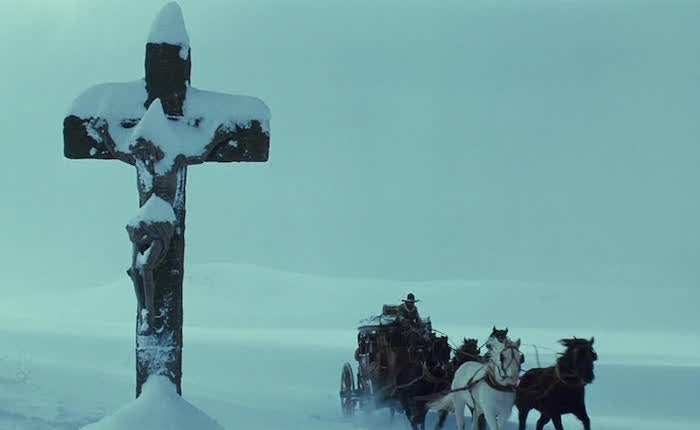

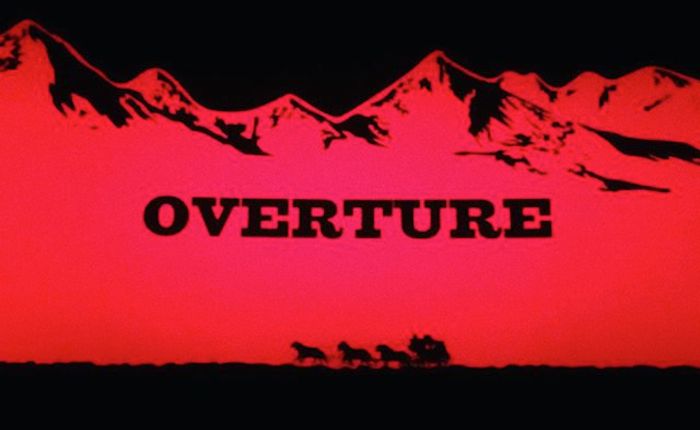

Ironically, while all these other films were epic spectacles, The Hateful Eight is more of a Kammerspiel, featuring a small cast and only two actual sets, a stagecoach and “Minnie’s Haberdashery,” where 75% of the action takes place. Tarantino opens the film with shots of a snowy mountain landscape that accentuate the extreme width of the image, while also riffing on Saul Bass’ opening credit sequence from The Big Country (1958), once the stagecoach rolls into view and the credits appear. Indeed, the previous overture title card with a stagecoach racing horizontally across the bottom of the screen directly quotes Bass’ one-sheet poster for the earlier film. The use of title cards for chapter headings, a favorite Tarantino device, also continually reminds the audience of the film’s extreme wide screen format, as do its blacks and whites which are brighter and deeper than any DCP. In another shot, the camera counter-intuitively focuses on an extreme close up of a stone crucifix in the snow, then very slowly tracks backward to reveal a stagecoach in the distance riding towards the camera, hinting that there will be plenty of martyrdom before the film comes to a close.

Once the film settles into its primary location, where bounty hunters and a gang of criminals essentially restage the Civil War through a cat and mouse game of words and bullets, the logic of Robert Richardson’s Ultra Panavision camerawork becomes apparent: through rack focusing and lighting, the choreography of bodies, the wide screen documents the characters’ changing alliances as they move about the haberdashery’s space. Interestingly, the lack of close-ups that usually promote audience identification with one character or another, means that we view individuals from a distance – which is appropriate, given the fact that even the most sympathetic characters are cold-blooded killers or are killed almost immediately after appearing on screen. Even the ending is a pyrrhic victory, as the two remaining combatants lie in pools of blood, more dead than alive.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation

Comments