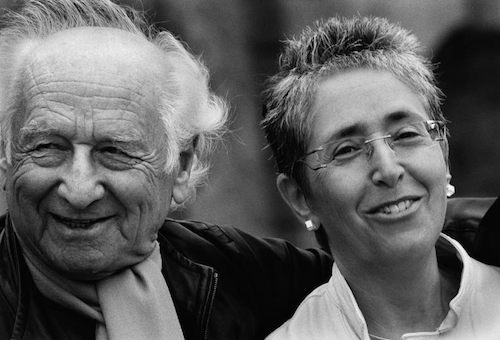

Arnošt Lustig with daughter Eva Lustigova

November 9 will be remembered forever after, because it is the day of Kristallnacht, the night of broken glass, when in 1938 the Nazi German government organized “spontaneous” demonstrations that lead to the burning of 267 synagogues, the trashing of 7,500 Jewish shops, and the murder or incarceration in concentration camps of over 30,000 German citizens of Jewish origin. This year, the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles invited guests for a Kristallnacht commemoration in honor of Arnošt Lustig, the Czech writer and Holocaust survivor, whose television film, A Prayer for Katerina Horovitzova (1965) was screened; a discussion followed with Lustig’s daughter, Eva Lustigova, and Lustig’s friend and collaborator, Czech New Wave film director Ivan Passer.

Born in Prague on December 21, 1926, Lustig was sent to Theresienstadt as a 15-year-old, then transferred to Auschwitz and later Buchenwald, before escaping from a train bound for Dachau. He returned to Prague to fight in the resistance movement. After the war, he studied journalism at Charles University, becoming a prominent literary figure in Communist Czechoslovakia, a friend of Václav Havel, and a public supporter of the Prague Spring. Lustig emigrated to the United States in 1968, when he and his family were in Italy the day the Russians invaded; there he eventually became a literature and film professor at American University. He moved back to Prague in 2004, where he died on February 26, 2011. In 2004, Lustig received the Arts and Letters Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and was awarded the Franz Kafka Prize in 2008.

Lustig’s New York Times obituary names him as “one of the greatest novelists of the Holocaust,” writing more than 20 books. His first collection of short stories, Night and Hope, was published in 1958, as was his short story about two Jewish boys who escape from a train heading to Auschwitz. The latter was adapted by Jan Němec for Diamonds of the Night (1964), an early Czech New Wave film, achieving international success. Lustig’s novella, A Prayer for Katerina Horovitzova became a worldwide bestseller, after it was published in 1964 (English, 1973). His other well-known works are Dita Saxová (1962), The Unloved: From the Diary of Perla S. (1979), and Lovely Green Eyes: A Novel (2003).

Diamonds of the Night (1964)

Modlitba pro Kateřinu Horovitzovou, its original Czech title, relates the story of 20 American Jewish businessmen who are captured by the Nazis in Italy in 1943 (after Mussolini’s fall) and sent to Auschwitz. They are told that for a fee they can be exchanged for some high ranking Nazi POWs. When one from the group buys the freedom of a young Jewish girl, she joins the convoy, which is driven around the Polish-German countryside, commandeered by Nazi SS Officer Brenske. The tragicomic farce ends in Auschwitz’s showers, where Katerina is forced to strip, pulls a gun from an SS officer and shoots him, leading to the death of all in a hail of bullets. The last incident was apparently based on a real event at Auschwitz, involving a Jewish woman from Warsaw named Katerina, who worked with the Nazis in the ghetto to entrap rich Jewish businessmen trying to get to America.

Dita Saxová (1968)

In 1965, Lustig wrote and directed a filmed version of his novella for Czech national television, co-directed by Antonín Moskalyk. Shot in black and white, the teleplay reduces the number of businessmen to six, who are initially incarcerated in an unknown location. When they hear the tortured screams of a woman, Mr. Cohen offers to also pay her passage to America. From the start, Brenske makes offers, if only they will pay, first for their train passage to Hamburg, then for their right to get on the boat, finally for their lives. Grotesquely, they travel in a luxury train, just as many Hungarian Jews did with destination Auschwitz. Every time they pay, there is another excuse why they can’t be released: the allies refuse the exchange, or deny visas or the Swiss have quotas. The Nazi Commander is surprisingly the most interesting character, always calmly soothing tempers, assuaging fears, excusing for bureaucratic procedures, apologizing for inconvenient snafus, lying and never telling the truth. The Jewish victims are individualized in the actors’ performance, but their common fate makes them the same as they cling to every last ray of hope, paying and paying again, until it finally dawns on them that it is all a scam and they are going to die. Lustig’s cruelest joke is that it is not a Yiddish Gesheftsman fleecing a customer, but the Goyim.

A Prayer for Katerina Horovitzova (1965)

The film, thus, becomes a parable for the fate of all European Jewry under the Nazis, many of whom went to their deaths without protest or revolt. Equally importantly, though, Lustig makes a point that has only recently been highlighted in the historiography of the Holocaust, e.g. in Götz Aly’s Hitler’s Beneficiaries (2006), which analyzes tax and confiscation records from the Finance Ministry of the Third Reich. Namely, that it was total economic exploitation of German and European Jews, the confiscation of all their wealth, which allowed the Nazis to finance WWII without burdening the German people with taxes. This point is made explicitly when Brenske admits the need for money to pay for the war and Schillinger asks, “Why did you start a war, if you couldn’t finance it?”

While Lustig’s teleplay could be mistaken for a piece of canned theater, at times, the powerful acting made it an emotional experience. It should also be remembered that such a work could not have been broadcast in Communist Czechoslovakia either before or after the brief period of liberalization, 1964-68. Thanks to the Czech Consulate in Los Angeles, we were able to see a rare transfer of this little-known film.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation