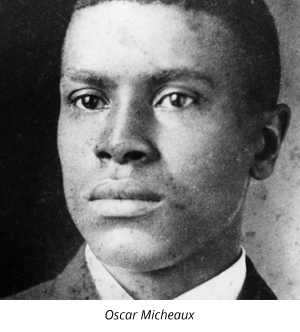

Back in February, I was contacted by a representative of Kino Lorber, which is releasing a Pioneers of African-American Cinema Blu-ray/DVD series. They wished to access our preservation print of Oscar Micheaux’s God’s Step Children (1938), one of the director’s later sound films (he would in fact only make four more films in the next 10 years). Unfortunately, this film by the most important independent African-American filmmaker of the first half of the 20th century has not yet been fully preserved, although it survives as a nitrate print. I had previously assumed that the push on a national level for access to African-American films in the 1980s had led to increased preservation in the archives. At George Eastman House, for example, we preserved Micheaux’s Veiled Aristocrats (1932) and Edgar G. Ulmer’s short Let My People Live (1939) with Rex Ingram starring as a Tuskegee Institute physician.

The reasons why God’s Step Children was overlooked by the preservation community are complex, including the fact that the film’s reputation among black film historians in the modern era was mixed, in part because it was outright rejected by the African-American press at the time of its release. Until the early 1950s, all-black cast films were screened in segregated theaters in the South (usually at black-only midnight shows) or at urban cinemas in the North, meaning their earnings potential was very limited and many of the white producers of so-called “race films” were bottom feeders. As a result, most film prints produced during the race film period are in extremely poor condition, making them less desirable as objects for restoration. In any case, we are now restoring God’s Step Children from analog elements, with the intention of home video distribution.

The reasons why God’s Step Children was overlooked by the preservation community are complex, including the fact that the film’s reputation among black film historians in the modern era was mixed, in part because it was outright rejected by the African-American press at the time of its release. Until the early 1950s, all-black cast films were screened in segregated theaters in the South (usually at black-only midnight shows) or at urban cinemas in the North, meaning their earnings potential was very limited and many of the white producers of so-called “race films” were bottom feeders. As a result, most film prints produced during the race film period are in extremely poor condition, making them less desirable as objects for restoration. In any case, we are now restoring God’s Step Children from analog elements, with the intention of home video distribution.

It was not until I started working on an essay this summer on the state of race film preservation for a forthcoming anthology by Barbara Tepa Lupack, Companion to Race Filmmaking, that I understood that the case of God’s Step Children is hardly unique. In fact, while the 1990s saw the high-profile restoration of several surviving independent African-American features from the 1920s – including Micheaux’s Within Our Gates (1920) and The Symbol of the Unconquered (1920), as well as the Colored Players’ Scar of Shame (1927) and MoMA’s more recent reconstruction of a never-completed Bert Williams feature, The Lime Kiln Field Day (1920) – there has not been a high-profile restoration project focused on the sound film era. The exception proving the rule, namely the Library of Congress’ restoration of The Emperor Jones (1933), based on Eugene O’Neill’s controversial play. The reason for the urgency in preserving black silents is clear, given the staggering losses from the silent era, but the reasons for the neglect of sound film are less clear.

Black film historians have long bemoaned the fact that, despite a rich history of independent African-American filmmaking during the silent era, almost nothing survives. In a 2013 study commissioned by the Library of Congress National Film Preservation Board, historian David Pierce placed the total percentage of American silent features that survive at about 25%. Approximately 20% of silent features produced with all-black cast film companies survive, many only discovered in the last two decades. The survival rate for black-produced silent narrative shorts is not much better at approximately 26%. The historical reasons for such low survival rates are many, including racism, poverty, lack of infrastructures for preservation, and the lack of continuity in that industry.

Astonishingly, 63% of all race film features made during the nitrate sound film era between 1930 and 1950 exist in some form, which is significantly higher than the alleged 50% survival rate of all American films from the nitrate era. And as much as 93% of all fiction and music performance sound shorts made with African-American performers survive. These survival rates can be credited to a dedicated group of African-American film collectors, including Pearl Bowser, Mayme A. Clayton and Henry T. Sampson, who carried together 16mm copies of many race era films. These black film archives have now been integrated into larger public film archives, e.g. the Mayme A. Clayton Film Collection is now deposited at UCLA. The survival rates, of course, only indicate that a film element has survived in some form into the present, in a public archive, and does not indicate quality of the material. In many cases, race film material only exists in degraded 16mm reduction prints, which were often endlessly screened in the past without any thought to making protection masters.

Midnight Shadow (1940)

Midnight Shadow (1940)

It could be that the very plentitude of surviving material from the 1930s and 1940s has led us to a false sense of security. Indeed, a number of better-known race films, e.g. Oscar Micheaux’s Swing! (1938), George Randol’s Midnight Shadow (1940), Hollywood Productions’ Harlem Rides the Range (1939) and Spencer Williams’ The Blood of Jesus (1941), are documented in at least four archives. Are they all from the same material? Maybe yes, maybe no.

In any case, new digital technologies do offer us a happy solution for the future, if archives can agree to begin a film by film comparison of surviving prints and then electronically generate the best possible montages of those prints into restored, complete films, allowing a new generation of African Americans and others to see what their and our grandparents and great grandparents saw.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation