Allá en el Rancho Grande (1936)

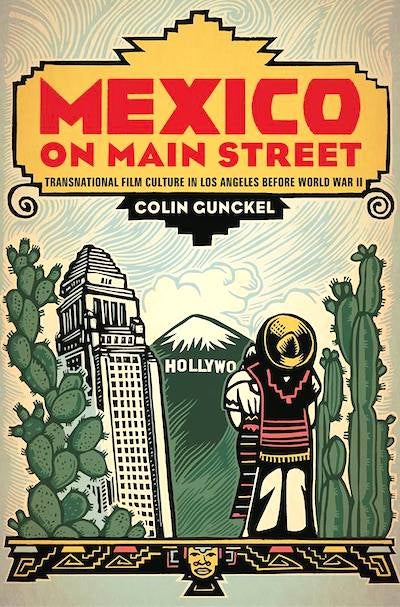

As noted in a previous blog, UCLA Film & Television Archive will be staging a major film exhibition in the fall of 2017, Recuerdos de un cine en español: Latin American Cinema in Los Angeles, 1930-1960, as a part of the Getty Foundation’s Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA initiative. Colin Gunckel, a member of our curatorial team and a professor at the University of Michigan, has recently published a book central to our topic, Mexico on Main Street: Transnational Film Culture in Los Angeles Before World War II (Rutgers University Press, 2015). Indeed, some of his research became the basis for our proposal to bring back to cultural consciousness the Spanish language cinemas that thrived in downtown Los Angeles from the 1930s to the 1950s.

My greatest epiphany in reading Gunckel’s book was to learn the degree to which the city fathers of post-WWII Los Angeles actively worked to eliminate all signs of Mexican identity in downtown through redevelopment, especially the traditional Mexican neighborhoods around North Main Street (where many of the Spanish language cinemas were located). Attempting to project an image of Los Angeles as WASP and middle class in order to attract new residents from the Midwest, the City tore down “unsanitary”  low-rent housing and constructed Olvera Street as a tourist attraction, recalling not its Mexican present, but a sanitized and romanticized historical Spanish colonial past. And while some Hispanic movie culture moved south to the Million Dollar Theatre on Broadway (at least temporarily), L.A.’s Mexican past was buried.

low-rent housing and constructed Olvera Street as a tourist attraction, recalling not its Mexican present, but a sanitized and romanticized historical Spanish colonial past. And while some Hispanic movie culture moved south to the Million Dollar Theatre on Broadway (at least temporarily), L.A.’s Mexican past was buried.

Gunckel begins his book by reconstructing a portrait of the Mexican community around the period of WWI, when a growing Mexican presence in Los Angeles was defining itself in terms of newspapers, like La Opinión, legitimate theatres, and other popular entertainments. Two particular issues seemed to concern the Mexican community; namely, its continued connection to the mother country, and the viciously racist stereotyping of Mexicans in American media as “greasers and thieves,” especially in silent films.

Once Hollywood began producing Spanish language sound films, such films became another bone of contention in the Mexican community because studio producers were completely deaf to the various  iterations of spoken Spanish, whether from Spain, Mexico or Argentina, creating a “war of accents.” As film critic Rafael M. Saavedra noted, Hollywood Spanish language films demonstrated “an absolute ignorance of our customs, our clothing, and our lexicon” (p. 99). Furthermore, by featuring Spanish actors who spoke Castilian, Hollywood was charged with denying work to local Mexican actors.

iterations of spoken Spanish, whether from Spain, Mexico or Argentina, creating a “war of accents.” As film critic Rafael M. Saavedra noted, Hollywood Spanish language films demonstrated “an absolute ignorance of our customs, our clothing, and our lexicon” (p. 99). Furthermore, by featuring Spanish actors who spoke Castilian, Hollywood was charged with denying work to local Mexican actors.

As Gunckel notes, sound also brought new Spanish language cinemas to downtown, which, due to the initially sporadic rate of production (in Hollywood, Mexico beginning in 1932, and later Argentina and Cuba), opened and closed with amazing rapidity. Not until after 1935 did the exhibition sector stabilize, a result of a boom in production south of the border. The increase in available Spanish language films from Mexico and Argentina led to a resurgence in L.A.’s Mexican cinemas, including the opening of Frank Fouce’s California Theater and Teatro Eléctrico in 1933, and the Hidalgo and the Teatro Mexico in 1936. Mexican film production had been catalyzed by the creation of the ranchero genre, after the huge commercial success of Allá en el Rancho Grande (1936), directed by Fernando de Fuentes. However, the film’s stylized and romanticized image of Mexico was not uncontroversial in L.A.’s Mexican community, even as it broke box office records in the same community.

By the end of the 1930s, Mexican films again went into decline, leading to the increased importation of Argentine films, so that Spanish language cinemas in Los Angeles presented mixed programs of Hollywood-made Spanish language films, Mexican, Cuban and Argentine films. This Hispanic film exhibition culture would not disappear until the early 1960s, a victim of assimilation, urban decay, and urban redevelopment. Colin Gunckel’s book is so important because it reminds us of all that has been lost.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation