Back in March 2010, George Eastman House announced the acquisition of Technicolor’s historic archive (1915 - 1974), including cameras, documents, drawings, photographs, printers, processing machines, corporate records and ephemera, that documents the Technicolor Corporation. The company is almost unique in the history of American cinema, in that it manufactured cameras and color film processes, but also produced films and directly influenced the look of many classic Hollywood films. Now, five years later, the museum has staged its first major exhibition from the collection and published a massive tome, The Dawn of Technicolor, 1915-1935.

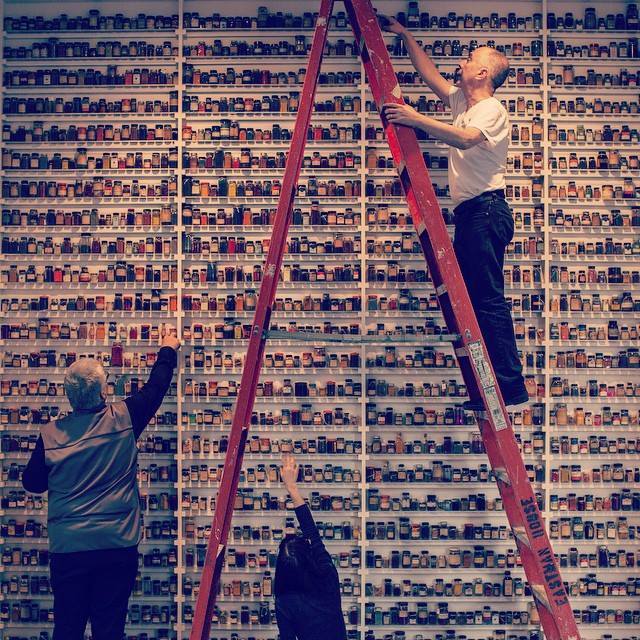

In Glorious Technicolor opened in January at Eastman House, and I got to see the exhibition in March. One of the show’s most impressive sights consists of a floor-to-ceiling shelf filled with a rainbow of bottled Technicolor dyes. Historic objects morph into art. Entering the exhibition brings you into a darkened space with three large screens projecting classic Technicolor features, beginning with Gone With the Wind (1939). The exhibition, which is modest given the breadth and depth of the Technicolor gift, consists of paper documents, photos of the principal actors in the company (including Herbert and Natalie Kalmus), cameras, some explanation of the Technicolor process itself, and homages to Technicolor cameramen, like Ray Rennahan and Jack Cardiff. My favorite piece in the show is the metal band used to keep the Technicolor matrices in registration, which is again presented as art, along with the technical diagram. Senior curator of motion pictures Paolo Cherchi Usai and his team are to be congratulated on a concise introduction to the history of Technicolor and its importance for the motion picture industry.

Accompanying Technicolor’s centennial year, Eastman House has published The Dawn of Technicolor, 1915-1935, a large format volume that is both a coffee table book and a work of serious historical research. The authors James Layton and David Pierce have combed through the surviving corporate papers to present a narrative in ten chapters of the company’s early struggles and its development of two-color Technicolor (1915-1935), before three-color Technicolor became the gold standard for the industry. The focus is on both business and technology. It is a history whose outlines were previously only visible in the technical literature on color film and in surviving two-color films.

The Technicolor story begins with two MIT graduates, Herbert T. Kalmus and Daniel F. Comstock, who formed a research company for inventing color film in 1912. At the time, the Kinemacolor Company of Charles Urban was having success with their additive color projection process, which alternated green and red frames. By 1917, Technicolor had developed a working additive two-color camera and produced a feature film in Florida, The Gulf Between (1917), which failed, however, due to lingering problems with projection. Over the next five years, Technicolor scientists would feverishly work to create a subtractive two-color process (red/green) ahead of their  competitors at Prizma Color and Eastman Kodak.

competitors at Prizma Color and Eastman Kodak.

In 1922, in a bid to convince Hollywood of the commercial potential of the process, Technicolor produced its second feature, The Toll of the Sea (1922), which was a commercial success, but still lost money for the company, because prints cost $1,245 each, or more than eight times the cost of black and white. Paramount followed suit with Wanderer of the Wasteland (1924), a Zane Grey western directed by Irvin Willat, but the production costs of color prints upended acceptance by the cost-conscious industry.

After Technicolor moved some of its operations from Massachusetts to Hollywood, Douglas Fairbanks signed on to produce The Black Pirate (1926), which would prove to be an artistic and commercial success for United Artists and Technicolor. The problem was that Technicolor prints were extremely fragile (having emulsion on both sides) and wore out quickly, necessitating the production of more prints. Thus, Pirate’s success did not translate into more contracts, rather: “Producers were now wary of the potential technical issues associated with the process, and were having second thoughts about incorporating significant color sequences into their prestige pictures…” (p. 141).

To make matters worse, MGM’s all-color extravaganza, The Mysterious Island was shelved in December 1926 after massive cost overruns. Meanwhile, Technicolor had developed a workable imbibition process and a split had occurred between Herbert Kalmus and Daniel Comstock, leading to Kalmus’ takeover of the company. In order to convince Hollywood of the viability of Technicolor, Kalmus returned to producing short films, forming Colorcraft Pictures with distribution by MGM. That lead to another boom in the late-1920s, followed by another bust, as quality issues continued to dog the company. More than once, Kalmus came close to calling it quits. Two-color Technicolor would in fact remain an exotic technology. The company would not be embraced by the studio majors until it introduced three-strip Technicolor with Disney’s Silly Symphony: Flowers and Trees (1932), financed the feature Becky Sharp (1935), and saw the end of the Depression. The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), The Wizard of Oz (1939) and Gone with the Wind (1939) would be the first fruits. But that’s already another story.

The authors weave all kinds of sidebars into their history of Technicolor and its product, including short biographies on all the principal players, discussions of competing companies and technologies, numerous illustrations, financial details and an excellent filmography. The aesthetic side does come up a bit short, as does Natalie Kalmus’ role as “Color Consultant,” a subject that certainly warrants further research. Layton and Pierce summarize contemporary reviews, but there are few discussions of the actual viewing experience. However, for everything else, this book will become the standard for Technicolor research.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation