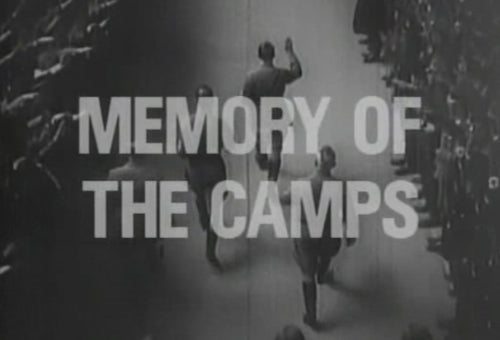

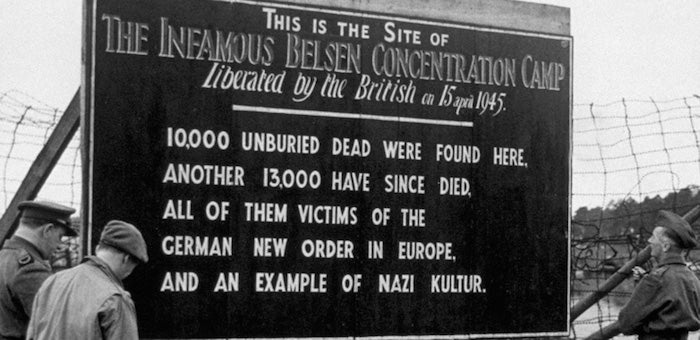

In honor of the 70th anniversary of the liberation of KZ Bergen-Belsen concentration camp on April 15, 1945 by British Army troops, the National Film & Sound Archive of Australia organized a screening of German Concentration Camps Factual Survey (1945/2014), formerly known as Memory of the Camps (1985) at the annual conference of the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF). Held at the Australian National Parliament in Canberra the day after the anniversary, the screening included introductions by Imperial War Museums (IWM) curator David Walsh and a daughter of one of the film’s original cameramen. Digitally restored by the Imperial War Museums, with a premiere at the London Film Festival last November and a screening at the Berlinale in February, the original film was directed by Sidney Bernstein, with Alfred Hitchcock functioning as a treatment advisor. Long available only in fragmentary form, the film had been shelved before completion in 1946 by the British Ministry of Information. I had seen a virtually silent 16mm version titled Memory of the Camps, missing reel 6, which had been shown at the Berlinale Forum section in 1984. A year later, a narration by actor Trevor Howard was added to the edit, as were undoubtedly various foleyed sound effects, when it was featured in May 1985 on television’s Frontline. Since then, the video version had become one of the most popular items in the Imperial War Museums’ catalog, screened 49 times between 1992-2008.

Like Stuart Schulberg’s Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today (1948), Factual Survey was suppressed almost immediately after World War II, because American and British government policy moved away from viewing the Germans as the perpetrators of war crimes to being our allies in the war against Communism. The new policy, brought on by the Cold War, not only allowed postwar Germans to turn themselves from a nation of perpetrators into a nation of victims (of Allied bombing), but also contributed to a decades-long mass amnesia about the Holocaust in Europe and America. Furthermore, U.S. Army psychological warfare experts had ascertained that German audiences forced to view Billy Wilder’s Death Mills (1945), which utilized similar footage, believed that the film was fabricated Allied propaganda. Watching Factual Survey’s images of German townspeople steadfastly looking away or at their feet when paraded before mass graves certainly seem to support the thesis of willful denial of responsibility.

IWM Senior Curator Toby Haggith has written about the film’s restoration in the latest issue of the Journal of Film Preservation, noting that IWM staff were unhappy with the videotape version, which apart from missing the last reel had been generated from a scratched and “dupey” work print. Finding the original shots in over 105 reels of raw footage proved challenging, as was the fact that they were working with original nitrate. Finally, there was a lot of guess work in putting together reel 6 from sometimes vague descriptions in the original shot sheets, as well as generating maps which had never been completed at the time of production. Finally, all new titles and a text prologue, explaining the film’s original purpose, had to be created and inserted. Sound effects were taken from numerous original sources and a new narration was recorded with stage actor Jasper Britton. A conscious decision was made not to include music, as originally planned in 1945, given the gravity of the images. The result of this careful archival labor is an extremely powerful film that left the FIAF audience in stunned silence.

Unfortunately, the completed six-reel version of Factual Survey was not only a document of Nazi atrocities, but also of anti-Semitism in the British government during World War II, especially the Foreign Office and the Ministry of Information, since the specifically Jewish character of the Shoah has been obscured to the point of invisibility. Certainly, we see unrelenting footage of emaciated corpses in gut-wrenching detail being dragged by well-fed Nazi guards of both genders. But the word “Jew” is almost never heard, except in the following: "We don’t know if they’re Catholics, Lutherans or Jews, only that they died in Belsen in agony." At the same time, the film includes images of Catholic clergy and nuns, and Christian crosses (a necklace on a corpse and painted on a man’s back), but there are no visual signs of the Jewish faith. This narrative of absence and invisibility makes this film an uncomfortable document of victors and war criminals.

< Back to Archival Spaces blog

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation