In my last blog I mentioned that a Gina Kaus novel formed the story for the Robert Siodmak comedy The Night Before the Divorce (1942). Another Kaus novel, Dark Angel (1934), became the basis for Edgar G. Ulmer’s Her Sister’s Secret (1946), which UCLA Film & Television Archive recently restored (it will screen at the Museum of Modern Art next week). In point of fact, the Austrian novelist eventually became a scriptwriter in Hollywood, after her exile from Austria, working on such high profile projects as The Robe (dir. Henry Koster, 1953) and All I Desire (dir. Douglas Sirk, 1953), both directed by fellow German-speaking émigrés. Although I have known about Kaus and her work in Hollywood, I was not really aware of her fascinating and unconventional life before she left Europe — she was a feminist ahead of her time.

Kaus was born Regina Wiener in Vienna on October 21, 1893, the daughter of a Jewish banker. She finished high school, and then married a musician at 20 — Josef Zirner, who fell on the battlefield in 1915, while Kaus continued to live with her in-laws. She next met the prominent Viennese Jewish banker Joseph Kranz, becoming both his lover and adopted daughter, while joining poet and Franz Kafka confidant Franz Blei’s writer’s circle (and becoming his lover). In 1917, her first play, the comedy Thieves in the House, premiered at Vienna’s prestigious Burgtheater. But her serious literary career began in 1921 when her novella, The Rise, won the coveted Theodor Fontane Prize. In the meantime, she had dropped her double name, Zirner-Kraus, to marry Otto Kaus, with whom she had two sons, before divorcing him. The mid-1920s saw her relocating to Berlin, writing for various Vienna and Berlin-based newspapers, and having an affair with Franz Xaver Graf Schaffgotsch, known as the “Red Duke” because he joined the Communist Party even though he was royal.

Her Sister's Secret (1946)

By the end of the 1920s, Gina Kaus had arrived. Her play Toni (1927), about a German flapper, was a huge success, playing all over Central Europe. Her first novel, The Lovers (1928) became an international bestseller for one of Berlin’s biggest publishing houses, Ullstein. It was a roman á clef about two couples who unwittingly switch partners, fictionalizing Kaus' initially unhappy relationship with lawyer Eduard Frischauer, and his wife, Ella, who had been one of her best friends. Frischauer would in fact become her long time companion, following her to Paris and Hollywood. Always a world champion bridge player and no longer being able to practice law, Frischauer became a compulsive gambler, whose debts Kaus inevitably had to pay. Indeed, evidence suggests that Kaus not only supported herself and her two sons, but also Frischauer, his wife and their daughter during much of their exile.

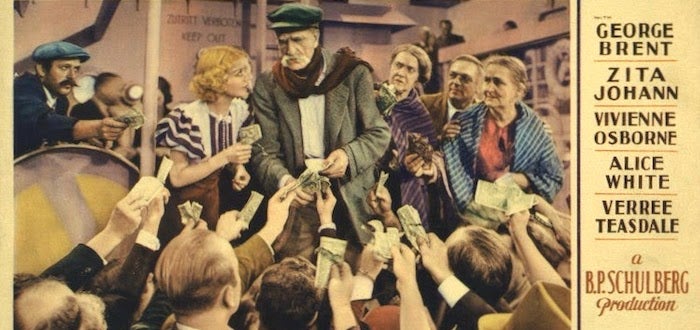

Luxury Liner (1933)

As a Jewish feminist and sexually liberated writer, it’s not surprising that she would become a target for the Nazis once they came to power. Her 1932 novel The Crossing was burned in May 1933 by the Nazis, at the same time it was adapted for a film at Paramount, Luxury Liner (dir. Lothar Mendes, 1933). Kaus returned to Vienna and made her first trip to New York when her novel, Catherine the Great (1935), became a bestseller in America. After the so-called Anschluss, Kaus fled with her two sons to Paris via Zurich on an Italian passport, where the literary agent Georg Marton introduced her to Austrian émigré film producer, Arnold Pressburger. The producer had bought a story from her, which became the highly successful Prison sans barreaux (dir. Léonide Moguy, 1938) and then put her under contract. In her autobiography, And What a Life, Kaus notes that she had a terrible time cashing the checks Pressburger gave her, because a single woman was not legally able to open a bank account without a husband, and she couldn’t prove that she had been divorced for over a decade.

Devil in Silk (1956)

With financial help from Georg Marton, Kaus obtained a visitor’s visa to America for herself and her children and arrived in Hollywood in November 1939. Marton sold several of her stories, so that her name appeared on four films in 1942, including an anti-Nazi film written with Jay Dratler, The Wife Takes a Flyer; a western, Western Mail; and a comedy, They All Kissed the Bride. After that, her productivity dropped a bit, but Kaus still regularly received film credits for stories or adaptations of her growing number of novels. Her most important later credit is a West German production of her novel, The Devil Next Door (1940), which Rolf Hansen directs as Devil in Silk (1956) with Curd Jürgens and Lilli Palmer. She traveled back to Berlin and Vienna in the early 1950s for visits, but decided to stay in Los Angeles, where she died in 1985. Only recently has there been renewed academic interest in her work, as Germanists discover the “forgotten” work of Weimar women novelists.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation