Last week we opened our new film series, “Exile Noir,” which I curated. While I occasionally conceptualize some of the Archive’s film programs, it so happens that I have been researching and writing about German-speaking exiles who fled Hitler and arrived in Hollywood for decades. Indeed, a few weeks ago I celebrated the 30th anniversary of receiving my Ph.D. for a dissertation on the topic.

After finishing my master’s thesis at Boston University, “Ernst Lubitsch and the Rise of the UFA,” I knew that for my next project I wanted to follow Lubitsch and his UFA colleagues to America. In the summer of 1975, I received a grant to interview German-speaking émigré filmmakers in Hollywood. Making my first trip to the West Coast, I interviewed more than a dozen individuals, including John Brahm, Joe Pasternak, Henry Koster, Wilhelm Thiele, Walter Reisch, Francis Lederer and Fritz Feld. I began a one-year internship at George Eastman House, and then moved to Italy, where I continued my exile research privately, completing a filmography of close to 500 people who had been forced to flee Berlin and Vienna after 1933. The fruits of that labor resulted in an introduction to my oral history, “The Palm Trees Were Gently Swaying: German Refugees From Hitler,” which was published in Image (1982).

I began a one-year internship at George Eastman House, and then moved to Italy, where I continued my exile research privately, completing a filmography of close to 500 people who had been forced to flee Berlin and Vienna after 1933. The fruits of that labor resulted in an introduction to my oral history, “The Palm Trees Were Gently Swaying: German Refugees From Hitler,” which was published in Image (1982).

In the meantime, I had enrolled in a Ph.D. program at the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität in Münster, Germany. Why there? I decided to go to Germany because the education was tuition-free if you were proficient in German, and because I knew my topic would be of more interest there. The caveat was that rather than simply applying to a university, you had to find a Doktorvater (literally “doctor father”—a thesis advisor) who agreed to sponsor you. After a couple of false starts in Berlin, Munich and Tübingen, I was accepted by Dr. Winifred B. Lerg, who was head of the Communications Department in Münster, where a budding interest in German exile studies was developing. Little did I know that a historiography of the Holocaust and surviving European Jewry was only then emerging in German academia, after having been suppressed for much of the post-World War II period. In Münster, I was one of several doctoral candidates writing about German Jewish writers, journalists and filmmakers who had gone into exile.

I argued that anti-Nazi films constituted a genre and that many émigrés were first hired [...] because Hollywood producers assumed they were experts in dealing with the Nazis and could bring a degree of realism to their propaganda efforts.

I continued my research over the next six years. In consultation with Prof. Lerg, I eventually narrowed my dissertation topic down to gauge the influence of German émigrés on Hollywood anti-Nazi films, rather than trying to cover all genres in which émigrés were prominent (film noir, historical costume pictures). I argued that anti-Nazi films constituted a genre and that many émigrés were first hired in the wake of Pearl Harbor, because Hollywood producers assumed they were experts in dealing with the Nazis and could bring a degree of realism to their propaganda efforts. Ironically, Jewish actors with German accents ended up playing Hollywood Nazis in countless films. I also deconstructed the films themselves in terms of their ideological content, comparing them to contemporaneous messages produced by anti-Nazi émigré writers and journalists in other media, noting that anecdotes about Nazi misdeeds often migrated from newspapers to non-fiction literature to film.

I continued my research over the next six years. In consultation with Prof. Lerg, I eventually narrowed my dissertation topic down to gauge the influence of German émigrés on Hollywood anti-Nazi films, rather than trying to cover all genres in which émigrés were prominent (film noir, historical costume pictures). I argued that anti-Nazi films constituted a genre and that many émigrés were first hired in the wake of Pearl Harbor, because Hollywood producers assumed they were experts in dealing with the Nazis and could bring a degree of realism to their propaganda efforts. Ironically, Jewish actors with German accents ended up playing Hollywood Nazis in countless films. I also deconstructed the films themselves in terms of their ideological content, comparing them to contemporaneous messages produced by anti-Nazi émigré writers and journalists in other media, noting that anecdotes about Nazi misdeeds often migrated from newspapers to non-fiction literature to film.

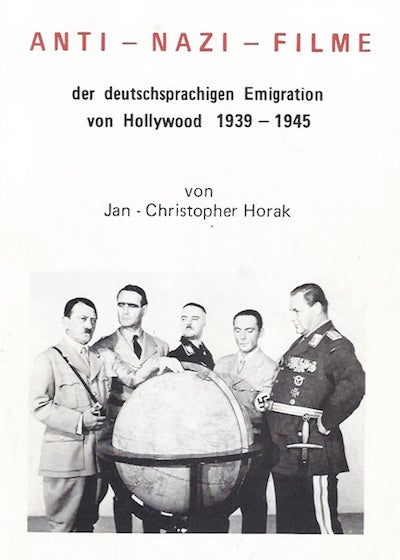

Meanwhile, I was taking courses in communications, history and American literature, teaching and learning Latin and academic German writing. Founded in 1780, Münster still required Latin proficiency as a Ph.D. requirement, so I technically could have written my work in Latin. I completed my dissertation, Anti-Nazi Films of German-Speaking Exiles in Hollywood, 1939-1945, in 1984, after which it was placed on display for public comment for six weeks, before it was officially accepted. Only then was I admitted to the so-called rigorosum, an oral exam encompassing my major and two minors. What’s more, I had to find professors in history and American lit who would agree to examine me, not a simple process, since the professor can ask you anything under the sun once you are standing before the committee. After successfully completing one seminar with a politically conservative history professor, it turned out that we had ideological differences in a second seminar, forcing me to find someone else only six months before the exams. Anyway, I passed.

My dissertation was published later that year and it became an unexpected bestseller for an academic press in Germany, possibly because it was one of the earliest book publications on German exile film. Unfortunately, the work was never translated into English—however, as Film-Talk blog has noted retrospectively, my book was the first “to shed a light on the exiled film-artists, which, until then, had been neglected by exile researchers who were concerned primarily with the literary and academic emigration.”

Over the years, I’ve returned to the topic repeatedly in various essays, but our “Exile Noir” film series is the first time that I have curated a German exile program at UCLA. And for those interested in anti-Nazi films produced by émigrés, the Skirball Cultural Center is presenting an exhibition in the fall, and I will also introduce Hangmen Also Die! (1943) there on October 30.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation