The Los Angeles Times broke the story on January 18: “Paramount stops releasing major movies on film” (latimes.com). Quoting unnamed Paramount executives, Times reporter Richard Verrier noted that Anchorman 2 was the last movie Paramount would release on 35mm film and DCP (Digital Cinema Package), while Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street would be the first to be entirely distributed in digital formats. Somewhat ironic, given Marty’s championing of film preservation and film culture. While the news did not come as any great surprise to any of us in the field, it certainly marks a milestone and another death knell for film as we know it. I was quoted in the piece and noted that 35mm had been the distribution medium of choice for 120 years, but that the end was now in sight, and it has come faster than anyone could have imagined.

the piece and noted that 35mm had been the distribution medium of choice for 120 years, but that the end was now in sight, and it has come faster than anyone could have imagined.

A week later, NPR picked up the story and interviewed me on Weekend Edition Sunday, specifically about the ramifications Paramount’s move had for film preservation. I had a lot more to say that was cut, but there have also been digital proselytizers on Twitter and NPR’s comment section who have been deeply critical of my remarks. So let me state my position in full, which I believe reflects the policies of my colleagues at the Archive (at UCLA and elsewhere).

It makes sense for Paramount (and the other Hollywood studios will certainly follow suite) to distribute their new films in digital formats, because it saves them huge distribution costs: namely, the cost of anywhere from 5,000 to10,000 35mm prints for a wide release, and shipping of the same. It also makes sense for them to produce films digitally and migrate them as new formats are developed, given that they can afford massive digital infrastructures (or are outsourcing the work, as in the case of one major Hollywood studio). However, there are ramifications that will affect other parts of the industry.

First, and possibly most importantly for the film archive world, with all the studios cutting down their usage of 35mm, it is likely that Kodak and other raw film manufacturers will come under even more economic pressure, and may even stop all production of raw film. That would have very serious consequences for all those film archivists who believe as we do that we should be making analog film negatives for long term protection of the material (more on that below).

Secondly, the few remaining film laboratories which process 35mm and 16mm film will also probably go out of business, as many already have. All the major labs have converted most of their operations to digital post-production and output.

Secondly, the few remaining film laboratories which process 35mm and 16mm film will also probably go out of business, as many already have. All the major labs have converted most of their operations to digital post-production and output.

Thirdly, while almost all of the cinema chains in this country have converted to digital projection, there remain a significant number of independent cinemas, art houses, and museum spaces (including our own Billy Wilder Theater), which do not yet have DCP systems installed. According to Variety: “At the end of the first quarter this year, the d-screen count stood at 94,638, plus 5,500 lower-grade e-cinema screens in India… With nearly 130,000 screens in the world, there are fewer than 30,000 35mm screens left to convert” (variety.com). I suspect that many cinemas will just close up shop, given that DCP installation runs anywhere from $80,000 and up, and 35mm screenings will no longer be an option.

Again, UCLA Film & Television Archive does see the advantages of digital tools for distribution and restoration work. We are working to vastly expand our website offerings, allowing patrons to stream selected films from the collection. Digital tools also allow us to do many kinds of fixes on damaged films that were not possible in analog processing.

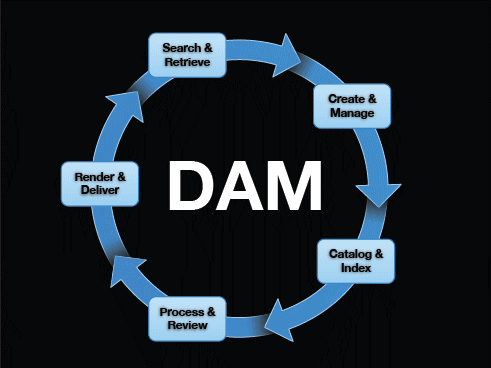

However, with new file formats appearing every 18 months to two years, with the cost of digital migration running as much as $15,000 per 90-minute film (as was the case when we

had to convert our LTO 3 tapes of The Red Shoes masters to LTO 5 tape), and with digital asset management systems running into the millions of dollars, we still believe filming out masters to 35mm film is the most cost effective way to guarantee the long-term survival of our moving image patrimony. Obviously, a time will come when this may no longer be possible, but until then, or until we have a more permanent digital file format, this remains our policy. Indeed, The New York Times only two days ago reported on the BBC’s late digital asset management system, which crashed and burned after the broadcaster spent £126 million converting their news library to digital files" (nytimes.com). Sure there was human error, but technology ultimately will always need human control that could fail, even if the system doesn’t. That is the lesson of this brave new world of digitality.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation