A year from now, UCLA Film & Television Archive will present a major film series and traveling exhibition, “Through Indian Eyes: Native American Cinema,” curated by a team of Native American filmmakers, Valerie Red-Horse and Dawn Jackson, as well as our head programmer, Shannon Kelley, and myself. I conceived the idea for the show when I realized how many films have been produced by Native Americans in the last twenty years, compared to virtually zero in the 95 previous years of cinema history.

So far funding has been secured from the San Manuel Band of Serrano Mission Indians and the Hollywood Foreign Press Association, and we are entering the heavy research phase of the project. With the involvement of Indian curators and filmmakers, we believe the Archive’s tour can function as a conduit for Native American voices into other centers of the cultural mainstream. Not only does UCLA thereby fulfill one of its missions to foster cross-cultural communication, it may also foster more films of all kinds from Native American filmmakers.

Coincidentally, Lee Schweninger’s Imagic Moments: Indigenous North American Film (University of Georgia Press) has just been published, representing the first serious academic study of Native American cinema. Previous publications, as well as a number of documentary films, have focused almost exclusively on the image of Native Americans in Hollywood cinema, including Victor Masayesva Jr.’s Imagining Indians (1992) and Neil Diamond’s Reel Injun (2009). However, as Schweninger theorizes, Hollywood’s indelible racist images of aboriginal peoples in North America are never completely absent from this new wave of films. Rather, by telling stories from the Indian perspective, they “talk back” to Hollywood, refuting long-standing stereotypes and other clichés of dominant cinema, often through intertextual references. The author also notes how often Native characters take control of the means of production by filming themselves and others, as well as how often filmmakers interpolate historical images of Indians, arguing that both strategies constitute resistance to Hollywood.

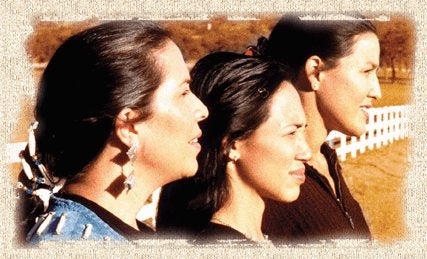

Schweninger defines indigenous North American cinema as being produced by Native Americans with Indian characters and actors, noting that “self-representation is a form of resistance and is necessarily a fundamental aspect of Indigenous film” (p.7). However, the author immediately places caveats on his definition when five of the first six films he discusses are directed by European-Americans, seemingly discounting their influence. Altogether, Schweninger presents close readings of fourteen fiction feature films in as many chapters, including Imagining Indians, Chris Eyre’s Smoke Signals (1998) and Skins (2002), Sherman Alexie’s The Business of Fancydancing (2002), Valerie Red-Horse’s Naturally Native (1998), Randy Redroad’s The Doe Boy (2001), Shane Belcourt’s Tkaronto (2007), Sterlin Harjo’s Four Sheets to the Wind (2007) and Barking Water (2009). In our own research, we have now identified more than 100 fiction and documentary shorts and features, written and directed by Native American filmmakers, of which only a handful were produced before the 1990s.

Another thesis developed by Imagic Moments posits that whereas Hollywood invariably portrays Native Americans as a doomed race, “the Vanishing American” earmarked for extinction by the U.S. Cavalry, Native American films very often feature characters who die during the course of the narrative but remain a living spiritual presence for the other characters. At the same time, these films are always about contemporary Indian life in the 21st century, indicating that Native Americans are far from extinct, even if they are often invisible to the dominant culture. Many of the films begin with the funerals or deaths of a loved one, leading younger members of the tribe to undertake road trips, which become journeys of self-discovery and identity formation.

Indeed, as one would expect of any “national” cinema in the throws of establishing itself, identity politics are central to these Indian narratives, whether concerned with life on the reservation or with Native Americans living in society at large. The discourse on Native American identity is invariably linked to the revival and cultivation of Indian culture, including its spiritual worldview, its languages, and its customs and traditions. And while some Native American film characters disparage “the old ways,” the stories clearly favor a rejection of the assimilationist policies long propagated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Thus, Native American actors visualize Indian stories created by writers and directors who have grown up in their own culture, demonstrating that neither the culture nor its members are extinct.

Finding a limited set of thematic and stylistic continuities in his selection of films from indigenous North American cinema, Schweninger teases out some characteristics of that cinema. But his film theoretical discussions are naïve, so his close readings harvest parts rather than wholes. And there are blind spots. In discussing The Business of Fancydancing, the author hardly touches on the fact that the central character is gay, thus avoiding discussion of Native American attitudes about sexual identity politics. In the case of Naturally Native, he concedes that the film is ground-breaking in its focus on Native American women, admitting that virtually every other film he discusses keeps women at the fringes of the drama, but then faults the film for being beholden to “mainstream colonist culture” (p.149) for its mores and morality, a charge that is both false and unfair, given that life off the reservation will always require a degree of assimilation, and does not automatically constitute a betrayal of Native American culture.

Finding a limited set of thematic and stylistic continuities in his selection of films from indigenous North American cinema, Schweninger teases out some characteristics of that cinema. But his film theoretical discussions are naïve, so his close readings harvest parts rather than wholes. And there are blind spots. In discussing The Business of Fancydancing, the author hardly touches on the fact that the central character is gay, thus avoiding discussion of Native American attitudes about sexual identity politics. In the case of Naturally Native, he concedes that the film is ground-breaking in its focus on Native American women, admitting that virtually every other film he discusses keeps women at the fringes of the drama, but then faults the film for being beholden to “mainstream colonist culture” (p.149) for its mores and morality, a charge that is both false and unfair, given that life off the reservation will always require a degree of assimilation, and does not automatically constitute a betrayal of Native American culture.

However, for anyone interested in this relatively new phenomenon, Imagic Moments is a good point of departure.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation