I’m starting to see lots of trailers for Gore Verbinski’s The Lone Ranger (2013), starring Armie Hammer as the masked man and Johnny Depp as Tonto. While Depp has made a career of playing exotic roles, I’m still shocked that the role of a Native American has gone to a Caucasian actor. One would have thought that fifty plus years after the Civil Rights movement began sensitizing most white Americans to the feelings of non-white ethnic minorities, Hollywood would have given up the practice of painting white actors either black, yellow or red. But now we have Johnny Depp in red face. Not even the original television series, “The Lone Ranger,” which ran from 1949 to 1957 and starring Native American actor Jay Silverheels, had done that.

Now, some will object that Depp has stated that he has Native American ancestry, but so do probably most 5th or sixth generation Americans (who also all probably have a few drops of African American blood), given the fact that interracial sex probably started in this country with the arrival of the Jamestown colony in 1607 (think of Pocahontas and John Smith). Supposedly, Depp’s great-grandmother was either Creek or Cherokee, – he doesn’t know which – which according to Depp, “makes sense in terms of coming from Kentucky, which is rife with Cherokee and Creek.” But Depp neither grew up dirt poor on a reservation, nor were his parents or grandparents subjects of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), nor was he socialized in a tribal culture. His make-up for the role of Tonto, it turns out, is based on paintings by the Anglo Kirby Sattler, another white man defining Native Americans as “mystical-connected-to-nature-ancient-spiritual-creatures, with little regard for any type of historical accuracy” (Native Appropriations).

Conveniently for Disney, Depp was adopted by the Comanche Nation during the filming of The Lone Ranger, which was a good PR move for both Depp and the tribe. Disney, for its part, courted Native American leaders, involving them in the script and production, thereby nipping any protests in the bud. Nevertheless, a controversy rages, because many commentators are as skeptical as I am about Depp’s Native American heritage. More importantly, Disney’s $250 million epic just continues a long, long tradition in Hollywood of casting non-white starring roles with European ethnics.

Until the late 1940s, Hollywood still employed “blackface” with abandon, thereby showing its own aesthetic roots in vaudeville and minstrel shows peeking through the glitz. Blackface was of course based on deeply entrenched racial stereotypes and caricatures. D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of the Nation (1915), for example, cast Caucasian Walter Long as “Gus, the renegade Negro.” In musical comedy, famously Al Jolsen, but also Eddie Cantor, Mickey Rooney, Judy Garland, and Irene Dunne, among many others, also appeared in blackface. After World War II the practice almost completely stopped, as the NAACP lead a boycott of radio shows such as “Amos and Andy,” where white actors mimicked African-American speech, a kind of aural blackface.

Hollywood, however, had no problems continuing the practice of yellow face and red face. D.W. Griffith cast Richard Barthelmess as a Chinese servant in Broken Blossoms (1919). Warner Oland and Peter Lorre made careers of playing Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto, respectively. As late as the 1960s, we get Mickey Rooney’s portrayal of a Japanese neighbor in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961), taking the prize for the viciousness of its racism. But red face, apparently, is still not a problem even today when dollars are at stake.

I was recently lecturing in Munich on Maurice Tourneu’s The Last of the Mohicans (1920), which starred Allan Roscoe as Uncas and Wallace Beery as Magua, both Caucasians. The two roles correspond to Hollywood’s positive and negative stereotype of the noble savage. The 1936 sound remake starred Bruce Cabot as Magua and Philip Reed as Uncas. Obviously, virtually all of Hollywood’s cowboys and Indians narratives were equally racist, but they did undergird the historical ideology of Manifest Destiny that justified the genocide of Native Americans. But even when Hollywood attempted positive portrayals of Native Americans, as in The Vanishing American (1925), which sympathetically portrayed life on a Navajo reservation, it starred a white actor, Richard Dix; likewise, Ramona (1928), starring Dolores Del Rio as a Native American woman, directed by Edwin Carewe, whose name was actually Jay Fox and of Chickasaw descent.

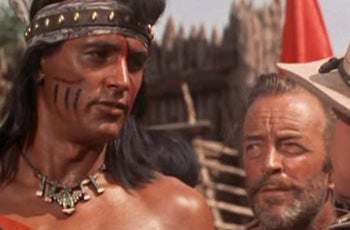

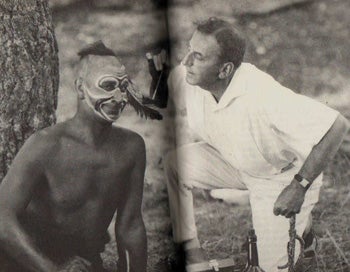

I was recently lecturing in Munich on Maurice Tourneu’s The Last of the Mohicans (1920), which starred Allan Roscoe as Uncas and Wallace Beery as Magua, both Caucasians. The two roles correspond to Hollywood’s positive and negative stereotype of the noble savage. The 1936 sound remake starred Bruce Cabot as Magua and Philip Reed as Uncas. Obviously, virtually all of Hollywood’s cowboys and Indians narratives were equally racist, but they did undergird the historical ideology of Manifest Destiny that justified the genocide of Native Americans. But even when Hollywood attempted positive portrayals of Native Americans, as in The Vanishing American (1925), which sympathetically portrayed life on a Navajo reservation, it starred a white actor, Richard Dix; likewise, Ramona (1928), starring Dolores Del Rio as a Native American woman, directed by Edwin Carewe, whose name was actually Jay Fox and of Chickasaw descent.

Personally, I grew up not only watching “The Lone Ranger” on TV, but also Hawkeye and The Last of the Mohicans (1957), starring Lon Chaney, Jr. as Chingachgook. Hollywood happily depicted famous Native American leaders as white men in red face: there was Jeff Chandler and John Hodiak as Cochise; Rock Hudson as Taza, son of Cochise; Chuck Connors as Geronimo; Burt Lancaster as Massai; Victor Mature and Anthony Quinn as Crazy Horse; J. Carrol Naish as Sitting Bull; Jody Lawrence as Pocahontas. Elvis Presley played a Native American, Joe Lightcloud, and Burt Reynolds starred as Navajo Joe. The list goes on and on. Now we can add Johnny Depp to the list, although it remains to be seen how realistic a portrayal he delivers. Frankly, I’m expecting a CGI extravaganza that is about as real as Depp’s cartoon pirate, Jack Sparrow.

Personally, I grew up not only watching “The Lone Ranger” on TV, but also Hawkeye and The Last of the Mohicans (1957), starring Lon Chaney, Jr. as Chingachgook. Hollywood happily depicted famous Native American leaders as white men in red face: there was Jeff Chandler and John Hodiak as Cochise; Rock Hudson as Taza, son of Cochise; Chuck Connors as Geronimo; Burt Lancaster as Massai; Victor Mature and Anthony Quinn as Crazy Horse; J. Carrol Naish as Sitting Bull; Jody Lawrence as Pocahontas. Elvis Presley played a Native American, Joe Lightcloud, and Burt Reynolds starred as Navajo Joe. The list goes on and on. Now we can add Johnny Depp to the list, although it remains to be seen how realistic a portrayal he delivers. Frankly, I’m expecting a CGI extravaganza that is about as real as Depp’s cartoon pirate, Jack Sparrow.

Works Cited: Adrienne K. "Johnny Depp as Tonto: I’m still not feeling 'honored.'" Native Appropriations.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation