I’ve been thinking a lot lately about Maurice Tourneur, who in 1920 directed what is one of my favorite silent films, The Last of the Mohicans. In a couple weeks, I will be lecturing on the film at the Hochschule für Film und Fernsehen in Munich, so I’ve been rethinking many of the ideas I first formulated close to the beginning of my career.

I first discovered the film as an intern at George Eastman House (GEH), sometime in the last century, when the only known print had come from the Cinémathèque francaise, so the 35mm nitrate only had French intertitles. During my post-graduate year at GEH, I literally discovered silent films. I had seen a few silent films during my studies, but now I was at the mother lode of archival American silent cinema, and realized the breath and depth of what that particular medium could be. I had seen some D.W Griffith films, but who knew about Maurice Tourneur, one of the great pictorialists of the cinema? Until James Card, my boss, showed me The Last of the Mohicans.

That year I published an article about the film and its relationship to James Fenimore Cooper’s 19th century novel of the same name, arguing somewhat heretically at the time that Tourneur’s version improved on the novel. When Cooper’s action gets bogged down in turgid prose, Tourneur’s narrative is always swift and concise. Where Cooper’s landscapes, for all their details, remain abstract, Tourneur’s landscapes are lyrical in their pictorial ambiance, as well as properly abstract in their meaning. While Cooper’s narrative oscillates uncomfortably between adventure and thinly achieved romance, Tourneur’s adventure is consistently and intensely romantic. A little more than ten years later, I was responsible for putting the film out on laserdisc.

That year I published an article about the film and its relationship to James Fenimore Cooper’s 19th century novel of the same name, arguing somewhat heretically at the time that Tourneur’s version improved on the novel. When Cooper’s action gets bogged down in turgid prose, Tourneur’s narrative is always swift and concise. Where Cooper’s landscapes, for all their details, remain abstract, Tourneur’s landscapes are lyrical in their pictorial ambiance, as well as properly abstract in their meaning. While Cooper’s narrative oscillates uncomfortably between adventure and thinly achieved romance, Tourneur’s adventure is consistently and intensely romantic. A little more than ten years later, I was responsible for putting the film out on laserdisc.

At the same time, I returned to the subject of Maurice Tourneur, in order to try and figure out why his career had gone down the tubes in Hollywood before the silent period even ended. He ended up directing films in Europe for at least another twenty years, while his son, Jacques Tourneur became a well-known Hollywood director of films, like The Cat People (1942), I Walked With a Zombie (1943), and Berlin Express (1948). Like D.W. Griffith, Mickey Nielan, Rex Ingram, and a host of other American directors who reached their stride in the mid-1910s, only to fall into unemployment, unproductivity or hackdom by the mid to late 1920s, Maurice Tourneur was a victim of the American studio system and the concomitant institutionalization of what has become known as classical Hollywood narrative.

Like Griffith, Tourneur fought against the encroaching power of the film monopolies, attempting not only to produce what he perceived to be high quality, artistic films, which went against the conventions of standardized, genre production, but also to polemicize against the overriding profit mania of the film factory. For a brief ten years, from 1914 to 1924, Tourneur maintained his status as an independent producer-director, financed for much of that time by the film entrepreneur, Jules Brulatour.

Like Griffith, Tourneur fought against the encroaching power of the film monopolies, attempting not only to produce what he perceived to be high quality, artistic films, which went against the conventions of standardized, genre production, but also to polemicize against the overriding profit mania of the film factory. For a brief ten years, from 1914 to 1924, Tourneur maintained his status as an independent producer-director, financed for much of that time by the film entrepreneur, Jules Brulatour.

It was the age before the moguls had invented the position of supervising producer as a watch dog over their "talent," and before the American film industry had evolved from an economic oligopoly of first and second generation film pioneers to a monopoly of film distributors, soon to be dominated by New York banking interests. Working best on his own with his own crew, including his trusted assistant Clarence Brown, Charles Maigne and Charles E. Whittaker as scriptwriters, cameraman John van den Broek, art directors Ben Carré and Floyd Mueller, Tourneur refused to become an interchangeable cog in the "Taylorized" film production system that was to become Hollywood in the 1920s.

"Watching The Last of the Mohicans yet again after so many years, seeing the intense beauty of Tourneur’s images, I realize again what was lost in the transition to the conventionalized cinema of genres that Hollywood would become in its classical phase."

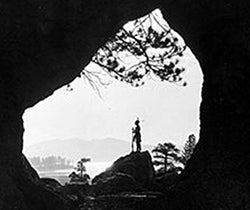

Richard Koszarski has called Tourneur the first of the visual stylists, and indeed Tourneur's particular style of filmmaking privileged the image over plot, mise-en-scene over montage, spectacle over narrative. In particular, Koszarski discusses Tourneur's use of theatrical space in his films, layering his images from foreground to background through lighting and the use of proscenium arches or masks. Here, too, Tourneur is swimming against the stream of Hollywood's film practice, which by 1918-1920 had internalized classical narrative modes, in the interest of what was perceived to be the most efficient means of subject construction.

In his best surviving work, one can see Tourneur clinging to conventions, which Noel Burch has called the "Primitive Mode," but which might better be identified as the road not taken by classical Hollywood cinema. Their visual theatricality and self-conscious compositions would be antithetical to the plot and logic driven narratives Hollywood would come to prefer. Likewise, Tourneur's oftentimes fragmented and episodic narratives consciously defy the rules of classical plot construction, as they were being formulated by industry practitioners. The downfall of Maurice Tourneur could thus be attributed to at least two factors, both related to his inability to integrate himself into the developing Hollywood studio system: 1.) Tourneur took a consistent political stand against economic and structural changes in the film industry, as it developed into a distributor-dominated monopoly and 2.) made films contrary to and polemicized against the institutionalization of the aesthetics of classical narrative.

Watching The Last of the Mohicans yet again after so many years, seeing the intense beauty of Tourneur’s images, I realize again what was lost in the transition to the conventionalized cinema of genres that Hollywood would become in its classical phase.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation