Last week at the Syracuse Cinefest, which convenes annually in March, UCLA Film & Television Archive presented a work-in-progress restoration of Partners Again (1926), a silent comedy feature. This one was literally snatched from the grave, but I’ll get to that in a moment.

Partners Again, directed by A-list director Henry King, was the third in a series of highly successful films built around “Potash and Perlemutter,” two Jewish, constantly bickering partners in the garment business on the lower East Side of New York, who then branch out into other financial adventures. Unlike the stereotypical Jewish characters populating most Hollywood films, who looked like they are fresh out of the shtetl, usually appearing as local color on the sidelines of the narrative, these families are thoroughly middle class, without outward signs of their ethnic heritage; a sign of the rapid assimilation and acculturation of American Jews in the 1920s. Their Jewishness is no longer visible in their dress, but only in the use of language in the subtitles, body language, and the audience’s acquired knowledge of the characters from previously published media.

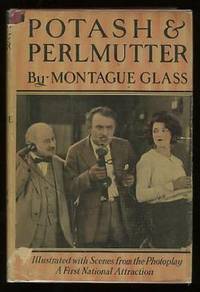

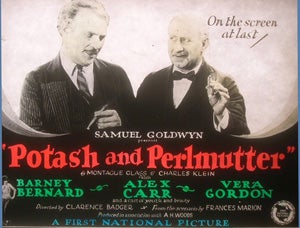

The films were based on short stories by Montague Glass, then turned into a Broadway play, “Potash and Perlemutter" by Glass and Charles Klein, which premiered to great acclaim on Broadway in 1905, and then successfully reprised in August 1913, running for 441 performances. The revival starred Barney Bernard as Abe Potash and Alexander Carr as Mawruss Perlemutter with Louise Dresser and Albert Parker in supporting roles. The authors wrote a half dozen more Broadway plays over the next decade, including “Partners Again,” which premiered in 1922 (with Bernard and Carr) and bombed, closing after less than six weeks.

It took almost two decades for a film version to appear, produced by Sam Goldwyn as his first independent film production, after being kicked out of his own company, just prior to the founding of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Unlike most Jewish Hollywood producers, Goldwyn was not afraid to address Jewish themes. Both Carr and Bernard reprised their roles in Potash and Perlemutter (1923), directed by Clarence G. Badger from a script by Frances Marion, but the rest of the cast was new, including Ben Lyon and Vera Gordon. The film concerned the partners’ new fitter, a poor Russian violinist who falls in love with Potash’s daughter, Irma. The New York Times critic was ecstatic, stating the comedy had “as many laughs as a Chaplin picture.”

Goldwyn, Marion, and Carr followed up with In Hollywood with Potash and Perlemutter (1924), Bernard having died in March 1924 at the age of forty-five. In the sequel, starring George Sidney (the uncle of the more famous film director of the same name) as Potash, the partners go West to get into the movie business, a journey Sam Goldwyn, formerly Schmuel Gelbfisz, had made himself, having started his business career as a glove maker.

Finally, in Partners Again, scripted again by Frances Marion, Potash and Perlemutter get into the automobile business, hawking the “Scheckmann Six,” a Jewish Ford, which was twice as expensive and half as good. The audience understands that both partners have no clue how an automobile works, creating much of the humor. As in the previous two films, the partners spend a great deal of quality time quarrelling, some of it at 10,000 feet on the top wing of a biplane.

None of the three Potash and Perlemutter films were thought to have survived. I first read about Partners in an as yet unpublished report by David Pierce about the survival of American silent films in any format, commissioned by the Library of Congress. Somewhere in a footnote David mentions Partners Again, noting that the only surviving material on the planet was on 8mm, housed at UCLA Film & Television Archive. I immediately asked my staff what had happened to the film and was told it was part of the old John Hampton Collection (now the Stanford Theatre Collection) and had been placed in the “dead vault” over ten years ago. That is the vault where we store hopelessly decaying acetate film, because “vinegar syndrome” produces highly acidic gasses that attack other films, forcing us to quarantine them. I felt like we had sent someone to the leper colony in Ben-Hur (1959).

None of the three Potash and Perlemutter films were thought to have survived. I first read about Partners in an as yet unpublished report by David Pierce about the survival of American silent films in any format, commissioned by the Library of Congress. Somewhere in a footnote David mentions Partners Again, noting that the only surviving material on the planet was on 8mm, housed at UCLA Film & Television Archive. I immediately asked my staff what had happened to the film and was told it was part of the old John Hampton Collection (now the Stanford Theatre Collection) and had been placed in the “dead vault” over ten years ago. That is the vault where we store hopelessly decaying acetate film, because “vinegar syndrome” produces highly acidic gasses that attack other films, forcing us to quarantine them. I felt like we had sent someone to the leper colony in Ben-Hur (1959).

I told my staff to get it out of there IMMEDIATELY, because I didn’t want the Archive to be responsible for the documented loss of a precious American silent film. Amazingly enough, we were able to get a passable digital transfer from the 16mm negative (actually 8mm up and down image). Michele Geary, our digital technician, then managed to stabilize the image, which bounced like a ping pong ball on the raw scans, and do some image clean-up. There are still focus problems, however, because the film is extremely warped, a sure sign of vinegar syndrome. Nevertheless, we are hoping to either rescan and get a better, sharper transfer or attempt to preserve in analog utilizing an optical printer.

In the meantime, the film was a hit in Syracuse and we can rest easier that it has been saved from utter obliteration. Given how few films Hollywood produced on Jewish themes (as compared to the Irish, who were considered safe), and even fewer that survived, this is a small victory for all of us.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation