I have been catching up on Netflix with some of Werner Herzog’s films made in the last ten years. Werner just celebrated his 70th birthday and unlike some of his compatriots from the German New Wave of the 1970s, he has not fallen by the wayside. On the evidence of recent work, his powers seem not only undiminished, but also more focused.

I first looked at Grizzly Man (2005) about a year ago and was very impressed with it, because while Herzog has always championed reckless dreamers, he clearly articulates the downside to such behavior here. Then, I saw The Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans (2009), which had an amazing performance by Nicolas Cage, and which Herzog made thoroughly his own, despite having to contend with Abel Ferrara’s 1992 original masterpiece, Bad Lieutenant. And then seeing Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010), Herzog’s documentary about the pre-historic cave paintings, discovered at Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc, France, I was blown away not only by the beauty of the caves, but Herzog’s sensitivity to the preservation issues. Now, I’ve just seen The Wild Blue Yonder (2005), which knocked me out, because Herzog essentially uses archival footage to create a film that is totally Werner. Seeing this work is a bit like meeting an old friend.

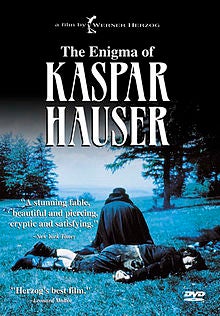

I occasionally met and had dealings with Werner when I was Director of the Munich Film Museum in the 1990s, since we had preserved virtually all his films, but I first started writing about him at the very beginning of my career in the 1970s. In “Werner Herzog’s Ecran Absurde” (Literature/Film Quarterly, 1979), I discussed what is still one of my favorite films of all time, The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (Every Man For Himself and God Against All) (1974), reading the film as both an homage to German Expressionist Cinema—specifically Lotte Eisner—and an existentialist meditation on life. A couple years later, I heard that the essay had caused a stir because the New German Cinema in general, and Herzog in particular, were understood to be sui generis, that is arising without precedent from German film history as a reaction to the “fathers” who had created Nazi cinema; and here I was a graduate student pointing out all the connections with German film history. In point of fact, even then Herzog was a master at creating what he called “never before seen images.” When I think back on Kaspar Hauser, now in reference to Wild Blue Yonder, I mostly remember Herzog’s montage of breathtaking images with a scratchy 78rpm recording of Richard Tauber singing the aria “This Image Is Enchantingly Lovely” from The Magic Flute. In Wild Blue Yonder, Herzog achieves an amazing otherworldly effect by again contrasting opera arias and his found images.

A couple of years later, I again wrote about Werner in “W. H. or the Mysteries of Walking in Ice” (The Films of Werner Herzog: Between Mirage and History, 1986), where I took the director a bit to task for some of his macho posturing in front of the camera. At the time, he had published a book (Of Walking in Ice) about walking to Paris from Munich in the winter to save Lotte Eisner’s life, a story that served to solidify Herzog’s reputation as somewhat of a blowhard more than anything else. Of course, his insane production shoots in the Amazon jungle for Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) and Fitzcarraldo (1982) had already made him a legend and even lead to lawsuits about reckless endangerment.

"And that is really the genius of Herzog: his ability to continually surprise us with images, seemingly from the everyday, which allow us to see the world anew and marvel at its beauty."

In any case, what I love about The Wild Blue Yonder is how Herzog has taken found footage and turned it into stunning images and sounds. The sci-fi story that Herzog creates as a frame is more or less incomprehensible, but no matter, because you can’t get enough of the images. The footage comes mainly from two sources: NASA footage of American astronauts taken during various space shuttle trips and Henry Kieser's incredible underwater images from beneath the Antarctic Ocean. Herzog takes what is familiar footage, and through music and editing turns it into something from out of this world. The seemingly slow-motion footage of astronauts maneuvering around the shuttle over Ernst Reijseger’s avant-garde music creates a truly alien world. Even more strangely beautiful is the underwater cinematography, lighted through the ice by a cool, blue illumination. Herzog again turns documentary shots into science fiction. And that is really the genius of Herzog: his ability to continually surprise us with images, seemingly from the everyday, which allow us to see the world anew and marvel at its beauty.

Mobile Navigation

Mobile Navigation